Neal Shusterman, Dystopian Optimist

The 2024 Margaret A. Edwards Award winner talks about hope, collaboration, and the school librarian who changed his life.

Cultures may differ, but kids are kids everywhere, says author Neal Shusterman, recipient of the 2024 Margaret A. Edwards Award, honoring a significant and lasting contribution to writing for teens.

The author of more than 30 books for children, teens, and adults, Shusterman has toured the world visiting schools and talking to students about his YA novels, which he hopes transcend time and place for his young adult readers.

[Register for live SLJ webcast: In Conversation with Neal Shusterman]

“The experience of being a teenager is a universal experience, which is why I think books are universal,” he says. “I love the fact that a story can be translated into any language, and it speaks to people in all these different cultures. My goal is to write stories that that transcend culture, that transcend time period, that 50 years from now will be just as relevant as [they are] today. I love the fact that when they do get translated, it kind of validates that and makes me feel as if the things that I’m putting out aren’t just the American experience [but the] experience for everybody.”

|

Neal ShustermanPhoto by Gaby Gerster |

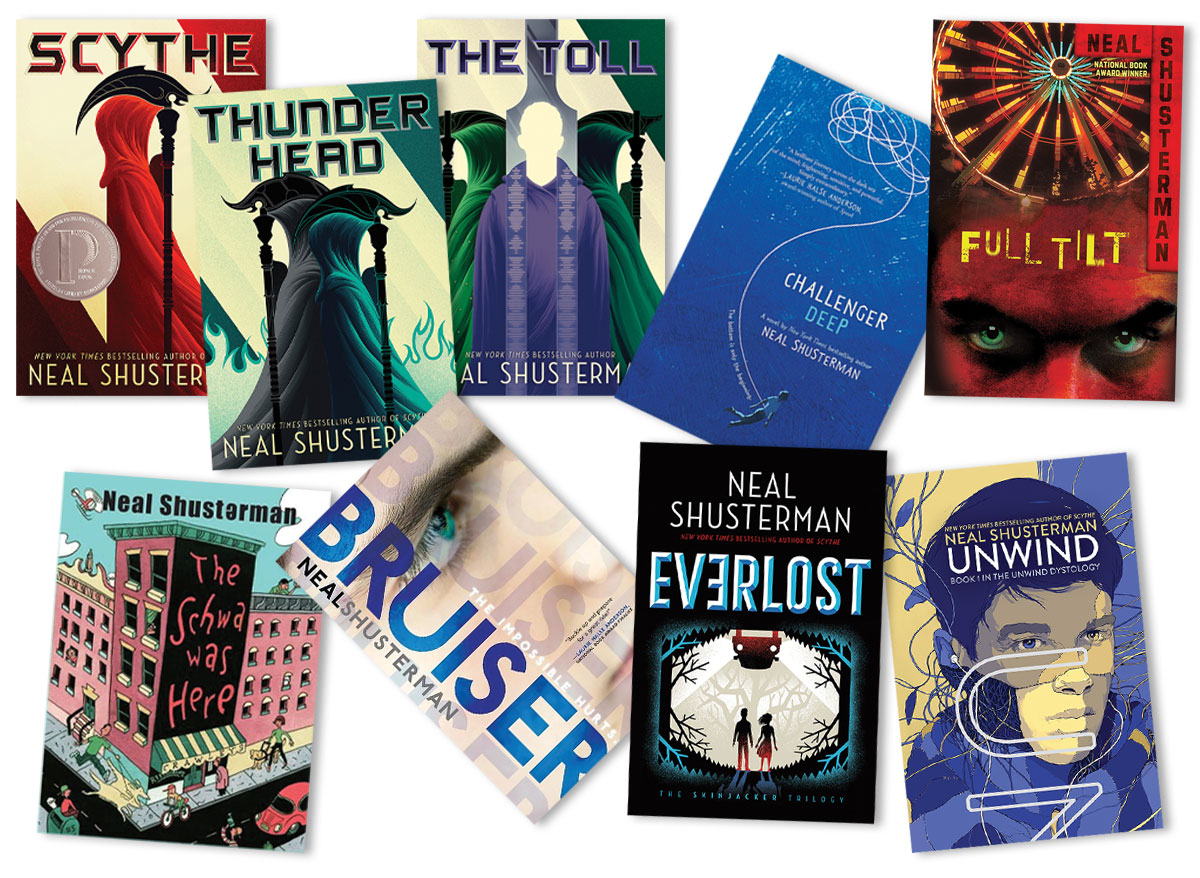

Shusterman’s YA novels are fantasy and dystopian. The Edwards committee chose to honor Shusterman for the “Arc of a Scythe” series, including Scythe, Thunderhead, and The Toll, as well as his novels Bruiser, Challenger Deep, Everlost, Full Tilt, The Schwa Was Here, and Unwind.

“I’m thrilled with the [books] they’ve chosen,” says Shusterman. “It really covers pretty much all the different types of things that I’ve done. And it went back to Full Tilt,” first published in 2003. “It’s always nice when some of the earlier books get recognition.”

It is the latest in numerous honors for Shusterman, who won the 2015 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for Challenger Deep and earned a 2017 Printz Honor for Scythe.

“Across genres for three decades, Neal Shusterman has met teens where they are by creating stories that center them as leaders, decision-makers, and agents of positive change,” Edwards committee chair Valerie Davis said in announcing the award. While much of his work is dystopian or deals with difficult topics, it all carries an optimistic core message.

“Central is hope,” says Shusterman. “I don’t like writing stories of futility. I want to write stories that bring something positive to the world. Even if the characters are going through some very difficult and dark places, it’s only so that they can get to a place of greater light. The idea is that [the story] can generalize to readers’ lives—no matter what you’re going through, no matter how difficult it seems, you’re going to get to a better place.”

But he doesn’t offer readers solutions to their struggles. Instead, Shusterman tries to echo the questions they may be asking themselves.

“I like to pose questions,” he says. “One of the things about the teenage years is, that’s when you realize that all those questions that had simple answers when you were a child—suddenly you realize there are no easy answers. That can be very frustrating.… People will ask, ‘What is the moral of your story?’ and moral implies that there is a simple answer. I don’t think I know what the answer is.”

A librarian’s impact

Shusterman’s rise to beloved and prolific author began in the unlikeliest way during elementary school, when a classroom teacher’s punishment and a librarian’s kindness sparked his interest in books.

As a third grader, he didn’t like reading and was not a particularly proficient reader, either. Shusterman also had a difficult relationship with his classroom teacher.

“She was very much a disciplinarian, and I was an undisciplined kid,” he says.

When he misbehaved, she sent him to the library.

“[That] was punishment for me, because I didn’t like reading,” says Shusterman. “But my elementary school librarian kind of took me under her wing.”

The librarian, Judith Shapiro, would let Shusterman be her assistant and open boxes of new books, allowing him to pick what he wanted to read before other students.

“I started really loving reading,” he says.

He went from barely reading picture books, by his own account, to reading Jules Verne at the end of the year.

“I remember reading Journey to the Center of the Earth and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ,” he says.

The paperbacks he read had binding issues, he remembers, causing the pages to fall out as they were turned.

“I really felt like [I was] consuming those books,” he says. “And I ended up being the best reader in my class by the end of that year.”

When he graduated from elementary school, he received the reading award.

“My elementary school librarian really made a huge difference in my life,” he says.

Shapiro made him a reader, which influenced him as a writer, even if he didn’t know at that time that’s what was happening.

“The things that you love definitely influence you as you’re growing up,” he says. “Everything from Roald Dahl to Jules Verne to [J. R. R.] Tolkien. When I was in eighth grade, I read Lord of the Flies. That really opened up my eyes to the idea of social commentary and metaphor in stories. I remember just loving that in the book.”

In ninth grade, Shusterman started to think of himself as a writer as well as a reader. It was the year the movie Jaws came out, and before ninth grade started, Shusterman wrote a similar story about a seashore town being attacked “by basically everything but a shark.” On the first day of school, he gave the story to his English teacher. She showed the principal, who entered it in a district contest.

“I didn’t win the contest, but I was flattered that my teacher [and] my principal thought that the story was well written enough to even enter it,” Shusterman says. “By the end of ninth grade, I really started to identify as a writer; I started to really just feel, ‘This is what I love to do.’ ”

It was among his many creative interests, such as art, music, and theater. “But by the time I got to college, writing emerged as the thing that I was most passionate about.”

He is also a screenwriter, working on television and film scripts, including adaptations of his novels. Multiple books are in development, among them Unwind and Challenger Deep as a series and film, respectively.

|

Shusterman captivates an auditorium.Courtesy of Neal Schusterman |

Collaboration

For many, writing is a solitary endeavor, but Shusterman isn’t always creating alone. He has collaborated with various authors during his career.

“I love the opportunity to write with other authors,” he says. “Sometimes your own head can be a lonely and scary place. It’s nice to have someone to be there with you while you’re working on these ideas.”

Most recently, he worked with two other writers, Debra Young and Michelle Knowlden, on a novel coming out this summer. It was his first time navigating the process with more than one collaborator.

“With three writers, there was a little bit of a learning curve,” he says. “Eventually, when you’re working with collaborators, you fall into a rhythm that works for you. It’s a little bit different with every person.”

With his son Jarrod he wrote both Dry and Roxy, the latter of which had a unique process, he says. First, the two sat together to plot out the story. Once that was decided, Neal would write one chapter and give it to his son for revision and notes. Jarrod would then write the next chapter and hand it to his dad to follow the same process. Perhaps most impressive, the story was told from multiple points of view, and father and son would alternate which of them wrote each character without disrupting the character’s voice or the continuity of the story.

“[Jarrod] was able to perfectly match the voice,” says Shusterman. “He was very, very good at it. And I was able to match [his] voice.”

While each collaboration is unique, one aspect is always the same.

“It’s never a matter of compromising,” he says. “One of the rules I always set in the beginning is that we both have to like it.”

If one of the writers doesn’t like something, there is no discussion, no argument. That piece is gone as they step back, think again, and work on something to replace it.

“What you come to realize really quickly is that you will always come up with something better than the thing that you came up with by yourself,” says Shusterman. “We trust that process. We don’t settle until we both come up with something we like even better than [what] was there before. And that always happens.”

What’s next?

While Shusterman recognizes the Edwards Award as a “lifetime achievement” honor, he is by no means near retirement. As a matter of fact, he may be more prolific than ever, with many book projects in progress.

He is writing a new series inspired by the pandemic. The first book is titled All Better Now, an “anti-pandemic story” about what happens when a virus makes everyone happy and takes away all emotional and psychological issues.

All Better Now will be released in 2025. But fans won’t have to wait until next year for new Shusterman work. His first romance novel, Break to You —the book cowritten with Young and Knowlden—publishes on July 2. He calls it “sort of Romeo and Juliet in a juvenile detention center.”

Meanwhile, Shusterman has just completed a deal to write a prequel to the “Scythe” series.

“It’s going to be about the beginnings of that world, when AI became the Thunderhead and gained consciousness,” he says of the book, which he anticipates will be out in fall 2025. “I realized that the original Scythes who started this probably were all teenagers who met on social media. And that’s where I’m starting.”

Like in all his work, the plot details will draw in readers, but there is substance beyond the mere summary of the story, says Shusterman.

“They end up getting something hopefully a lot deeper and more thought-provoking than they were expecting.”

Kara Yorio is senior news editor at SLJ .

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!