Mind Your Library Manners: Teaching Kids to Treat Books and Others with Respect

These librarians convey the rules with a light touch.

|

Courtesy of Cheryl Wolf |

Related Reading: |

When librarian Cheryl Wolf meets new elementary students each fall, she teaches library etiquette with the help of visual aids that show what not to do. “What do you think happened?” she asks students, holding up a water-damaged book with wrinkly, warped pages. “What would you do to prevent this?”

For the past 20 years, Wolf (pictured above) has served the Neighborhood School and STAR Academy, which share a building and library on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City. Her back-to-school slideshow also includes a photo of a ransacked bookcase with books on the floor.

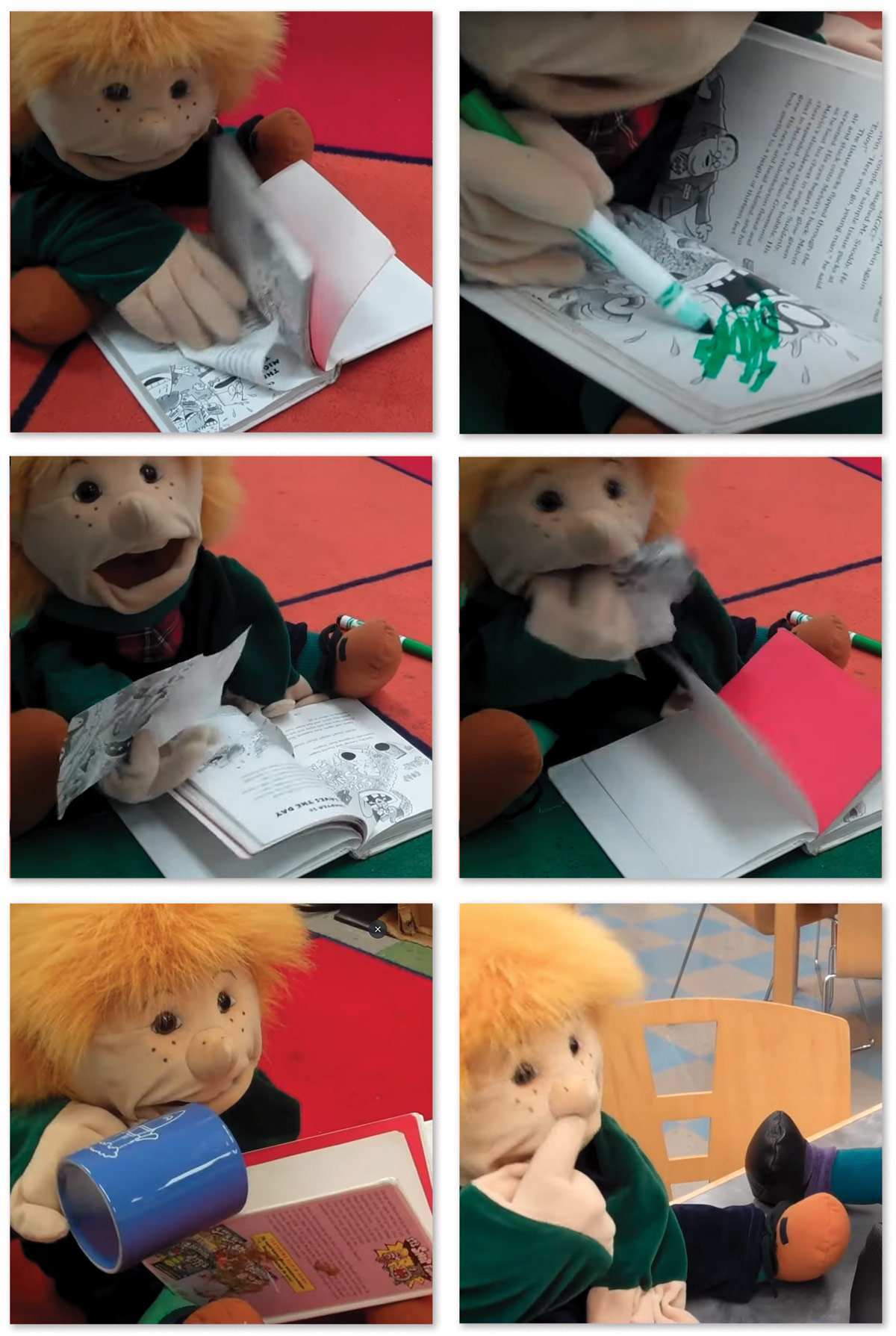

The new school year is a great time to introduce rules or refresh students’ memories on library “dos” and “don’ts.” When Rachel Wasserman did her student teaching at an elementary school, she and her colleagues conveyed those rules with a light touch. Wasserman created a seven-and-a-half minute video about book care starring a muppetlike character named Mr. Ginger who gets himself into trouble playing soccer with books and leaving them outside. Wasserman is now librarian at Bard High School Early College in Baltimore, MD, but the video she created is still wildly popular with elementary librarians: it has received more than 350,000 views on YouTube.

|

Don’t do what Mr. Ginger does.Video stills from Mr. Ginger: How to Take Care of Library Books |

Visuals such as pictures or videos are one way to invite conversations about how to behave responsibly in a library, but librarians have an array of strategies to encourage good behavior. Tracy Miller Prien, a library media assistant at Stayton (OR) Elementary School, teaches “audience manners” every year to her K–2 students. First, she asks students if they know how to be good audience members in a movie theater or at a play. Then, before she starts reading, she gives students a countdown: “Three, two, one, zero!” to help them settle down.

Prien, who brings 22 years of combined experience in museum education, reading, English Language Learning, and librarianship to her work, finds the countdown method effective. “By the second or third week of school, I am able to [count down silently] with my hand without voicing it,” she says.

If her students are too boisterous during book selection time, Prien—like many librarians—uses a musical chime to get their attention. In her case, she presses a doorbell, and then she asks if students are using their library voices. Like Wolf, Prien also asks questions that invite students to reflect on their behavior, since students often self-correct and get back on track when given the opportunity. “At this age, I would rather them be excited about books and remember it being fun” than quell their excitement, she says.

Others have their own strategies to use silence to gain kids’ attention. When Kyle Lukoff, children’s author and Newbery Honor recipient for Too Bright to See (Dial, 2021), reads to children at school and bookstore events, he draws on years of experience reading aloud to preschool and elementary students. As a librarian at Corlears School in New York City, Lukoff used the “power of silence” to communicate expectations to a listening audience. “Both as a librarian and a visiting author, I have had great success with saying to a chitchatting group, ‘I am going to wait for you to finish your conversations,’ and then actually and truly remaining silent until they stop talking,” he says.

Lukoff acknowledges that when he was a librarian, there were occasionally intractable classroom dynamics that were “in need of more direct intervention.” However, some groups of children are able to quiet down on their own and guide one another toward proper behavior. Sometimes a child who is eager to hear a read-aloud will shush her classmates and say, “Hey, I want to hear the story.” In situations like that, students help one another stay on track.

Etiquette for line waiting and book shopping

Waiting in a long line can be a trying experience for anyone. Some librarians hand students puzzles or Rubik’s Cubes to help kids pass the time. Fish tanks by the circulation desk can also offer low-key entertainment to kids awaiting checkout.

Keeping a consistent library routine with visual cues also helps children understand the librarian’s expectations. One tip to support line etiquette: put down three or four foot-shaped floor markers to indicate how many students should wait in the checkout line at a time, and how far apart they should stand.

When it’s time for Prien’s students to transition from one space to another, she will “dismiss them row by row after story and remind them that they are in a library and they should use their level-one inside voices,” she says. “I have also put a small carpet in front of my checkout desk, and the rule is only one student on the rug at a time.” In addition, Prien affixes circle shapes to the carpet with Velcro to guide students’ movement through the library.

“After checkout, students know the expectation is to sit at a table or my other big carpet and read with a friend or by themselves,” Prien says. “I also have a ton of book character plushies that they are allowed to grab and read with—as long as they are using their library manners. They get one warning and then the reading buddies have to be put back.”

|

The library at Our World Neighborhood Charter School, elementary in Astoria, NY, complete with fish tank and foot-shaped floor markers.Courtesy of Our World Neighborhood Charter School |

Minding manners outside the library, too

At the Geneva (IL) Public Library District, picture books are organized by subject categories, and the “Growing Up” area includes an entire category on manners. The ideal book on manners crosses over with other endearing topics such as “animal friendship,” says collection management librarian Erin Wittry, who purchases books and then decides on their best location. “Fun and entertainment is how [kids] digest information,” adds Lynne Schick, coordinator of Geneva Library’s Kids Landing, a literacy and learning space with play structures and STEAM activities.

Wittry and Schick agree that parents are more likely to seek out books on child-specific topics, such as being afraid of the dark, than good manners. But kids will get on board with most any story if the book is funny—for example, one about a giraffe apologizing to a worm for borrowing his socks without permission ( How to Apologize by David LaRochelle).

Entertaining books like this can reinforce good routines at both school and home, though some lessons can take time. Lukoff takes a long view when considering how to support students to be good citizens in the library and beyond. “These are difficult skills for children that take years for them to develop and internalize,” he says. “I keep myself focused on the long game.”

Jess deCourcy Hinds is a librarian at two International Baccalaureate campuses of the Our World Neighborhood Charter School, serving elementary and middle school students in Queens, NY.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!