Jim Crow in the North | Black History

Spotlighting the history of Jim Crow and civil rights struggles outside the South, along with recent books and teaching resources on the topic.

|

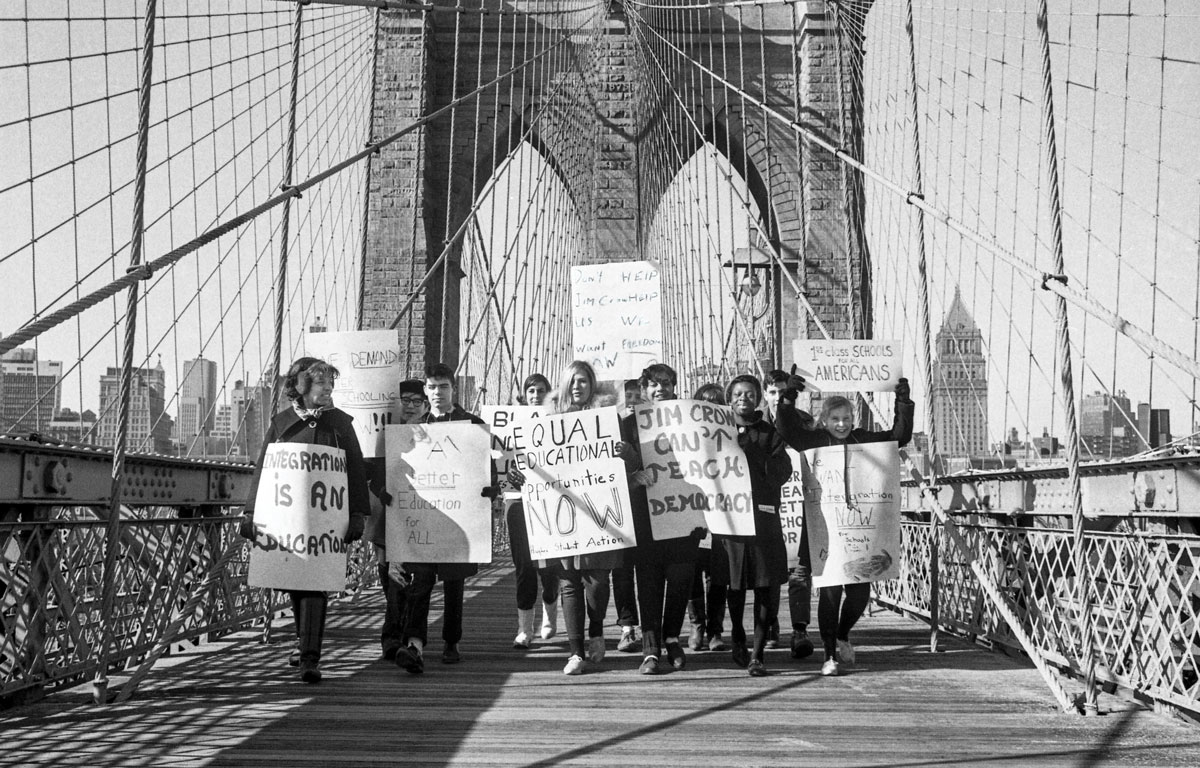

New York City School Boycott, February 3, 1964. Picketers march across the Brooklyn Bridge en route from City Hall to the Board of Education in Brooklyn to protest de facto segregation in the city’s school system. More than one-third of New York City public school children boycotted.Bettmann Archive/Getty Images |

I grew up in the 1960s in a small Northern city during a bitter school desegregation struggle, with my white liberal family fighting alongside others for a fully integrated school system. And yet, I learned from my family that most systemic racism happened in the South, and that Northern segregation developed because of the individual prejudice of neighbors, realtors, and others. So when I thought of civil rights, I most often thought about stories of Little Rock, AR, or Birmingham, AL.

I am not alone. When Adam Sanchez asked his New York City high school students where the biggest civil rights protest of the 1960s took place, they only named places in the South.

“This, of course, was no shock to me,” Sanchez, an editor of Rethinking Schools magazine, writes in his article “The Largest Civil Rights Protest You’ve Never Heard Of: Teaching the 1964 New York City school boycott.” “Despite obligatory coverage of the Civil Rights Movement in every history textbook, I have yet to find a single K–12 textbook that mentions the boycott against segregated schools in which 464,361 students…stayed home from school.”

[Also read: Teaching Black History Now]

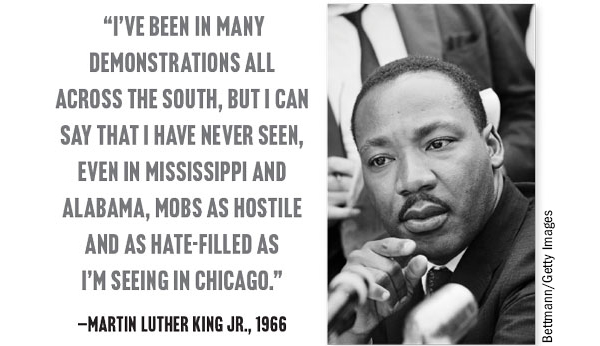

Sanchez points out that the prevailing narrative of the civil rights movement “tells a story of a movement that exclusively fought against racist laws in the South.” He adds, “This narrative reinforces the myth of progress, one in which most Americans, especially those in the North, responded positively to the demands of the Civil Rights Movement and righted the wrongs of lingering Southern racism.”

That was the narrative I learned in childhood. As an educator for 40 years, I read many books about racism and civil rights with my adult students and their families, but never looked critically at the fact that almost all the books I used took place in the South. Since participating in an antiracism course in 2022, I have been doing a lot of thinking and learning about the history of segregation and civil rights struggles in my hometown—Englewood, NJ—and the North in general. I’ve read many adult and children’s books; conducted online searches for photos and newspaper articles; and had numerous conversations with Black and white peers from Englewood, as well as Black families with life experience in the North and the South from 1940 to 1970 and professionals involved in civil rights research and teaching outside the South.

|

A recent display with recommendations by the author at the Easthampton (MA) Public LibraryCourtesy of Easthampton Public Library |

I began to wonder how today’s students learn about civil rights and what picture books and chapter books on the topic are shared in classrooms and libraries. So I investigated.

The New York City Public Library catalog lists some 270 books on civil rights for 5- to 12-year-olds. Out of that number, only about 7–10 picture books (depending on how broadly the time period is defined) tell stories of Jim Crow or civil rights outside the South.

This absence is reinforced by the dearth of photography telling the story of Jim Crow in the North compared to, for example, photos students often see of segregated water fountains in the South. Although there were, in fact, federal, state, and local laws and regulations outside the South that mandated segregation, less explicit strategies were more often used to keep Black people out of communities, developments, schools, swimming pools, ice skating rinks, and elsewhere, using euphemisms like “exclusive and restricted area” and insisting that certain recreational facilities were for “members only.”

Even historical organizations often lack visual evidence of segregation. The Civil Rights Heritage Center in South Bend, IN, is in a building that once housed a segregated public swimming pool. “Since Northern segregation was more undercover, the physical artifacts of it are less present here than in the South,” says George Garner, the center’s assistant director and curator. “To the best of my knowledge, there was never a sign on this pool. Word of mouth made it clear whether and when people were or were not welcome.”

A great visual resource for teachers and students of all ages is the photo documentary book North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South by Mark Speltz (Getty, 2016). While this book is a good source for photos of this period, it does not feature much direct evidence of the racism that led to the events portrayed.

A great visual resource for teachers and students of all ages is the photo documentary book North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South by Mark Speltz (Getty, 2016). While this book is a good source for photos of this period, it does not feature much direct evidence of the racism that led to the events portrayed.

Although books about civil rights in the North are limited, there are titles to help teachers and librarians balance their collections so that students will understand the nationwide nature of Jim Crow and the civil rights movement.

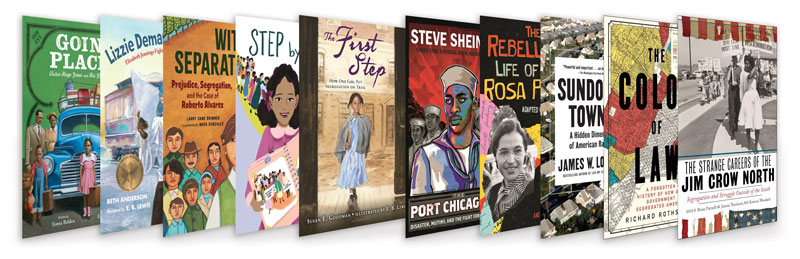

Of three picture books about the Green Book, only one—Going Places: Victor Hugo Green and His Glorious Book by Tonya Bolden, illustrated by Eric Velasquez (Quill Tree, 2022)—makes clear that the Green Book was created by a letter carrier who lived in Harlem and had a postal route in Leonia, NJ, a few blocks from my home. In fact, early editions of the Green Book, first published in 1936 to help Black families traveling by car identify hotels, restaurants, and gas stations likely to serve them, included only listings in the New York metropolitan area. Later, other states were added.

In teaching about well-known figures like Rosa Parks, teachers and librarians can bring in stories from the North as well. A century before Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus, Elizabeth Jennings, a New York City teacher, was forcibly removed from a streetcar because she was Black. Her story is told in the picture book Lizzie Demands a Seat! Elizabeth Jennings Fights for Streetcar Rights by Beth Anderson, illustrated by E. B. Lewis (Calkins Creek, 2020). And to help children understand Parks’s life after the bus boycott, middle grade and young adult students can read The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, Young Readers’ Edition, adapted by Brandy Colbert and Jeanne Theoharis (Beacon, 2021). The book includes chapters about Parks’s years fighting for civil rights in Detroit, which she described as “the Northern promised land that wasn’t.”

To help students understand the fight to desegregate schools across the country, teachers and librarians can share the picture book Step by Step!: How the Lincoln School Marchers Blazed a Trail to Justice by Debbie Rigaud and Carlotta Penn, illustrated by Nysha Lilly (Daydreamers, 2023), which tells the true story of how parents and children fought to integrate schools in Hillsboro, OH, in 1954. To provide historical context for the violence that erupted in Boston in the 1970s, adults and children can read and discuss The First Step: How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial by Susan E. Goodman, illustrated by E. B. Lewis (Bloomsbury, 2016), which tells the story of a fight for school integration in Boston more than 100 years earlier.

Other picture books can broaden children’s understanding of groups besides African Americans who were also the targets of segregation or exclusion. Without Separation: Prejudice, Segregation, and the Case of Roberto Alvarez by Larry Dane Brimner, illustrated by Maya Gonzalez (Calkins Creek, 2021), describes segregation of Mexican American children in San Diego schools in the 1930s. Mamie Tape Fights to Go to School: Based on a True Story by Traci Huahn, illustrated by Michelle Jing Chan (Crown, 2024), tells the story of Chinese American children excluded from school in San Francisco in the 1880s.

Middle and high school students can learn about the history of Levittown, popular suburban developments built between 1947 and 1971 in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere that forbade sale or rental to Black families. The Color of a Lie by Kim Johnson (Random House, 2024) is an excellent YA historical fiction book about Levittown. Discussion questions are available on the author’s website. Older students can also learn about some little-known history that took place in 1944 California by reading The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights by Steve Sheinkin, which portrays the glaring injustice Black men in the U.S. Armed Forces experienced during World War II (Square Fish, 2017).

A number of relevant books for adults have been published over the last 20 years; excerpts, photos, or chapters from these books can be used with high school students.

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein (Liveright, 2017) lays out the laws and policies of the Federal Housing Authority that established or maintained segregation throughout the country. The Strange Careers of Jim Crow North: Segregation and Struggle Outside of the South (NYU, 2019), edited by Brian Purnell and Jeanne Theoharis with Komozi Woodard, debunks the myth of Jim Crow as purely Southern, including examples of conditions in New York City; Los Angeles; Milwaukee; Rochester, NY; and Detroit.

In Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism by James W. Loewen (Touchstone, 2006), the author shares his extensive research about towns in which Black people had to leave by sundown or face arrest and violence—which he has documented largely in the Midwest and other Northern locales. Loewen and those who took over his research after his death created an interactive map of likely sundown towns across the country, which students and teachers can use to examine the history of segregation in their own cities and towns.

To teach the fuller history, educators need to supplement these books with videos, photographs, newspaper articles, oral histories, lesson plans, and excerpts from material for adults. Here is a listing of more books and other resources I have compiled to get you started.

We cannot allow another generation of children to believe that Jim Crow policies or conditions were restricted to the South. Providing your students with a national picture of Jim Crow and civil rights struggles will help them to use their knowledge of history to better understand and confront racism in the United States today.

An educator for more than 40 years, Alice Levine is active in social justice causes, particularly immigration justice.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!