Is Unrestricted Checkout Overdue?

Two school librarians fielded a study on unrestricted checkout and other aspects of circulation. This is what they learned.

Over the past few years, many school librarians have reevaluated their fine and late fee policies, realizing that the benefits of not charging fines outweigh those of collecting them. Some students stopped coming to the library or checking out books because the worry of potential financial cost hung over their heads. Without fines, circulation increased and more books were actually returned to libraries. The pandemic accelerated elimination of late fees in libraries.

Fines for overdue and lost books aren’t the only barriers to student checkout, however. Policies regarding when, what type, and how many books a student is allowed may also prevent students from accessing materials. The American Library Association (ALA) and American Association of School Librarians (AASL) affirm “the importance of having open, unrestricted, and equitable access to a school library’s resources and services.” Since the organizations promote open access, we assumed that school libraries would be adopting these student-friendly circulation policies. But in our conversations with other librarians, we learned that few schools had moved to unrestricted checkout, including some in our district, where equitable access is a paramount goal. We surveyed a larger group of librarians, wanting to know if what we were seeing reflected the current landscape of library practices. Were school library circulation practices becoming more open? Were more school librarians allowing unrestricted checkout?

The School Librarian Survey

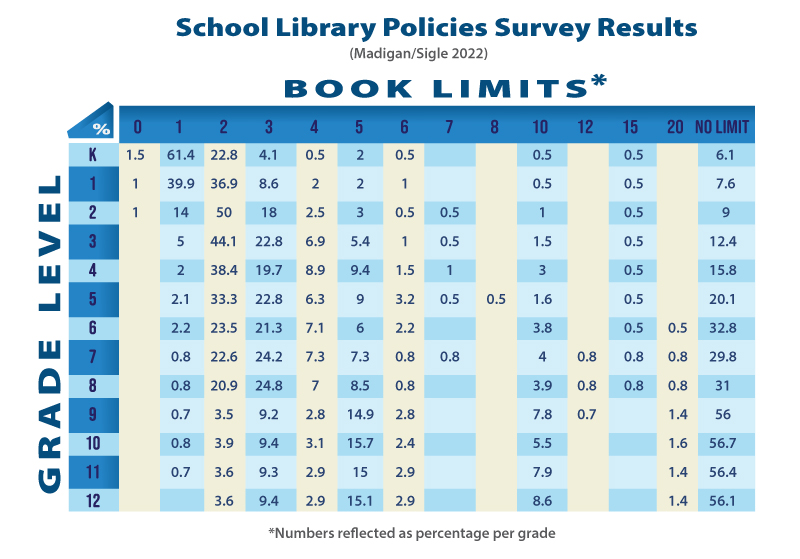

We surveyed 426 K–12 school librarians from forty-seven states and nine countries in December 2021 and January 2022. Participants could respond anonymously to the Google Form. Questions included the number of books allowed at each grade level, any limitations on type of books allowed, if librarians charge fines for lost/damaged books, and whether they restrict checkout for overdue books. We also asked participants to discuss their rationale behind these policies.

The results

The data and responses suggest that “unrestricted, equitable access” is open to interpretation. Ninety-four percent of respondents don’t charge fines for overdue books, and 11 don’t charge for lost or damaged books. Many found alternate ways for students to replace books or to take responsibility without causing financial hardship. That suggests that school library policies are changing to meet students’ needs. But there are some areas where school library policies haven’t evolved as much.

Limiting the number or type of books

One practice that doesn’t follow the ALA guideline of unrestricted access involves limiting the number of books for checkout. Almost seventy-two percent of the librarians set a limit. Kindergarten through second grade are the most restricted, often limited to one or two books.

The most common justifications for restricting number of books were to teach responsibility, limit the number of books to be reshelved, and perpetuate a policy already in place. Other responses mention preventing book loss and trying to keep parents and teachers happy.

Although most respondents place some checkout limits, only 32 percent report other types of limits. Many policies put a limit on popular series books in an effort to provide equitable access to all students, not just the lucky few who get to the graphic novel section first. The ALA’s “Access to Resources and Services in the School Library: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights” objects to school libraries “imposing age, grade-level, or reading-level restrictions on the use of resources…establishing restricted shelves or closed collections; and labeling.” It seems that most school librarians are following these guidelines.

Student responses to checkout blocks

Forty-nine percent of respondents block checkout entirely if a student has overdue books. This number is significant. For some students the school library is their only source of books. Although most communities have public libraries, many families don’t use them. Preventing students from checking out, sometimes for weeks or months, can seriously affect their academic success and relationship with reading. Being singled out for having overdue books can feel like punishment, and students might develop negative feelings for libraries and books in general.

We also surveyed 205 former students about their experiences in school libraries, and the responses suggested lasting effect from this policy. We asked, “If you were unable to check out books, how did this make you feel?” Among the 63 responses, the most common responses were sad, embarrassed, disappointed, ashamed, frustrated, and upset. One respondent wrote, “I thought others were saying things about me when I couldn’t check [out] a book.” Another declared, “I remember being really afraid of going to the library.” These are not the kinds of feelings we want our students to experience, nor the library memories we want them to carry forward.

This practice can be time-consuming for librarians too, since a list of students with overdue books is most likely generated beforehand. Students who can’t check out need to be informed, which can be embarrassing even when done discreetly. They also have to be engaged while the rest of the class looks for books.

At the beginning of our careers, we used to block checkout for students who had several overdue books. We realized the practice was not productive and abandoned it. The policy was potentially damaging to our relationships and chipped away at the welcoming, safe environment we wanted to promote.

The benefits of unrestricted checkout

Why set a limit at all? Why not let each student decide, not only which, but how many books they need each week? Unrestricted checkout benefits both students and librarians in several ways.

● Students are more likely to develop a positive attitude toward reading when given the opportunity to choose from a wide array of reading materials.

● Students are able to explore different genres and new interests with less pressure to find the perfect book.

● This encourages independence and critical thinking skills. In school, students have few chances to make their own decisions. We should empower them whenever possible.

● Students who aren’t restricted to “just right” books can challenge themselves with harder books. They might also check out books to read to younger siblings or with parents.

● Librarians will spend less time on administrative tasks to monitor checkout limits.

● Unrestricted checkout cultivates an atmosphere of trust and respect between the librarian and the students. Those who enjoy visiting the library are more likely to behave appropriately and to continue patronizing libraries throughout their lives.

Elementary school librarians, whose students often have designated checkout times, have the opportunity and responsibility to cultivate positive library experiences. Unrestricted checkout in elementary school libraries helps to build a strong foundation for middle and high school. Our student survey showed that the number of students who visited the library weekly dropped from 65 percent in elementary school, to 30 percent in middle school and 24 percent in high school. Closing the gap in these statistics could be another benefit of unrestricted checkout.

Managing unrestricted checkout

Some librarians might be reluctant to try unrestricted checkout. Perhaps they’re afraid they won’t be able to manage checking in and shelving more books, or they worry about book loss.

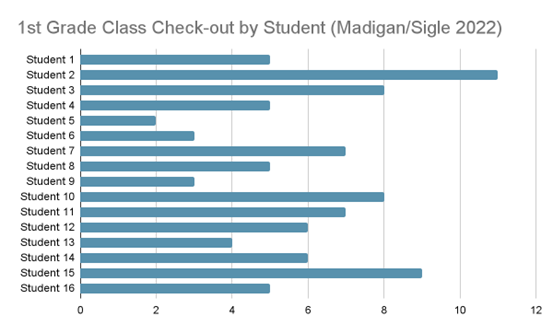

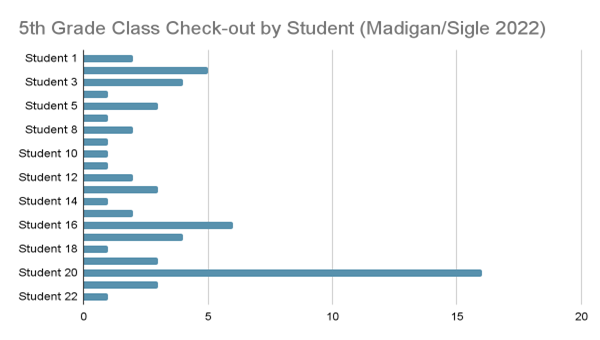

Maura found that she could provide all the benefits of unrestricted checkout without staying until midnight to shelve books. Although she’s a one-woman show without an assistant or volunteers, checking-in, checking-out, and shelving every book takes only about 1-1.5 hours a day.

Kim experienced a circulation surge when unlimited checkout began, but it was short-lived. Students quickly found the right cadence of how many books to take each week. Circulation increased but was still manageable. More importantly, the number of lost and overdue books decreased when students felt more in control.

Before students check out in our libraries, they’re asked to think about how many books they need that week and what kinds they want. They’re also asked to consider how many they still have from the previous week, and how much free time they’ll have to read. This sets the stage for thoughtful selections, rather than a rush and grab of books. Limits are placed on the number of books from popular series, but the only limit on the total number is that students must be able to comfortably carry their books. Most students now check out fewer than five books each week.

Providing rolling carts to classrooms so that returned books can be wheeled to the library each morning allows time to check in, sort, and shelve books when there’s a free moment. Teaching students how to access their library accounts to renew and check due dates helps most students avoid having overdues.

When a student with overdue books comes to check out, we let them know which books need to be returned, ask if they want to renew them, and print out a receipt for them to take home. Most students want to return books on time, but sometimes they need support. Providing this,and giving them the freedom to make mistakes, will ultimately help them succeed.

It took years for most school librarians to eliminate overdue fines. Perhaps the open checkout trend will follow a similar pattern. As school librarians see the benefits of unrestricted checkout policies, they might begin to change their library circulation practices. It’s possible since the majority of respondents (95%) indicated that they had input into, or were the person who made, the policies for their libraries. Why not consider trying unrestricted checkout, even on a trial basis? This would be an important step in making the library a more welcoming, inviting, and safe space for students.

School libraries have been in the national press recently, battling censorship and book bans. Being in the spotlight reminds us that it’s a perfect time to examine and reflect not only on our collections, but on our library policies. For many students, school librarians are the gatekeepers to the world of books and pleasure reading. Are your policies welcoming students in or shutting them out?

Maura Madigan is an elementary school librarian in Fairfax County (VA) Public Schools. Follow her on Twitter @MauraMadigan7. Kim Sigle is an elementary library educational specialist for Fairfax County (VA) Public Schools. She can be found on Twitter @FCPS_ElemLib.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!