Getting It Right: Sensitivity Readers Help Ensure Authentic Characters

Increasingly, sensitivity readers play a role in the editorial and publishing process. Experts in a specific identity, they often undertake research to provide detailed feedback on a manuscript.

|

Left: Author Ruth Spiro (at right) with sensitivity reader

|

No one sets out to write an insensitive book, says Jen Malia, author of the “Infinity Rainbow Club” chapter book series. “Yet many do so unintentionally.”

Classic children’s books are full of insensitive and hurtful portrayals, such as racist examples in Dr. Dolittle and Dr. Seuss. Some critics have objected to what they see as ableism in “magical cures” in books such as The Secret Garden and Heidi. But recent books have also prompted an outcry for racial insensitivity, from the picture book A Birthday Cake for George Washington for its illustrations of an enslaved man to the YA novel Dumplin’ for its reference to spirit animals, which the author removed after the first printing in response to criticism.

|

Author Jen Malia with titles in the “Infinity Rainbow Club” seriesPhoto courtesy of Jen Malia |

To ensure authentic representation, publishers and authors like Malia increasingly turn to sensitivity readers, who are hired to review manuscripts in order to provide clarification and insight into the marginalized identities portrayed.

Sensitivity readers are experts in a specific identity, usually the same as the characters they’re assessing. Some undertake research to provide detailed feedback.

While the process is becoming more common—a standard part of the workflow for many mainstream publishers, according to Jenna Lettice, a senior editor at Random House—it’s still relatively new and frequently misunderstood. A Guardian article claims sensitivity readers are “publishing’s most polarising role.” Some claim it’s a form of censorship and that concerns raised over misrepresentation stifle an author’s creativity. Others say that authors are being bullied by publishers if a sensitivity reader finds issues.

But these arguments give too much power to sensitivity readers: They are simply a part of the editorial process to improve a manuscript. They don’t make changes, nor do they decide whether a book is published.

Erin Olds, chief executive officer at Salt and Sage Books, an editing company that provides sensitivity readings among other services, explains it this way: “If you were to write a book about rockets, you’d do research. You’d learn as much as you can. But in the end, unless you’re also a rocket scientist, there are going to be things that you missed. You’d want to hire a rocket scientist to double check your rocket content.”

Olds adds, “The same holds true for writing diverse characters. When you write outside of your own lived experiences, you can—and should—do lots of research and learn as much as you can. But…research is no replacement for lived experience. That’s why you hire a sensitivity reader. They help you get things right in your story.”

While these readers help to flag any harmful stereotyping in a manuscript, it’s ultimately up to the author and editor whether to make changes based on the feedback.

Authors who appreciate this addition to the editing process include Saadia Faruqi, who works as a sensitivity reader as well. “I want my books to be not only factually correct, but not hurtful or harmful to any group of people,” says Faruqi.

“Kids deserve that,” adds Ruth Spiro, author of the “Baby Loves the Five Senses” board books and other works.

|

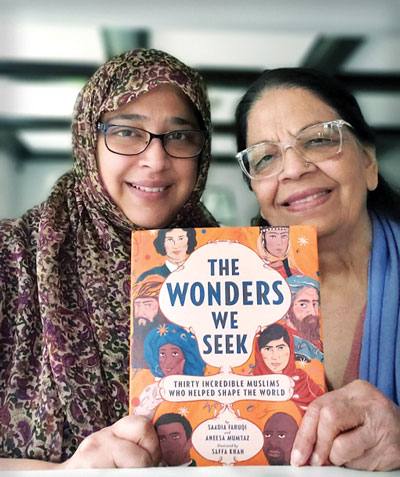

Saadia Faruqi (left) with Aneesa Mumtaz, her mother and coauthor of The Wonders We SeekPhoto courtesy of Saadia Faruqi |

Diverse books movement

Along with a focus on diversity in children’s fiction, the last decade has spotlighted positive and harmful representations of diverse characters. Organizations such as We Need Diverse Books, founded in 2014, and social media platforms have provided a space to raise awareness.

For Olds and others, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC)’s Diversity in Children’s Books graphics in 2015 and 2018, showing the lack of diverse representation in children’s books, were watershed moments in these discussions.

“I knew representation was bad before, but I didn’t have numbers to put to it,” says Olds.

Jenna Beacom has been a sensitivity reader for deafness since 2016, when discussions about authentic representation were exploding online. She says, “Black Lives Matter in 2020 really contributed a lot to the discussion of representation, racism, who writes what, what to do if you are writing outside of your experience.” There also was more discussion on Twitter about works that were inauthentic or otherwise problematic in their representation, like American Dirt (Flatiron, 2018), in a way that got publishers’ attention as something they wanted to avoid in the future.

American Dirt was criticized for its inaccurate and stereotyped portrayal of Mexico and Mexicans. But authors and publishers seek out sensitivity readers to ensure balanced representation, not just to avoid scandal.

“In my experience,” says Olds, “the majority of authors seeking sensitivity reads really, really believe that diversity and representation are deeply important, and want to have a positive impact on the world around them.”

|

Editor Hannah Gomez, Ruth Spiro, author and

|

How it works

The process can start in different ways. Some authors seek these consultants, while others request their publisher find one. And publishers may hire sensitivity readers with or without the author’s knowledge.

Andrea Beatriz Arango requested that her publisher hire a reader for her middle grade novel in verse, Something Like Home (Penguin Random House, Sept. 2023). A secondary character, Benson, has sickle cell disease, and Arango wanted to ensure she captured him well. “While no one person can represent an entire group,” she says, “it’s still important to seek out and listen to those with lived experiences.”

Her editor didn’t know of a sensitivity reader with sickle cell disease, so Arango found someone through her bookstagram community. “[The reader] was very generous in sharing her lived experience with me, and that helped me bring more nuance to Benson’s character than I would have been able to simply based on online research,” Arango says.

Spiro also suggested hiring sensitivity readers for her “Baby Loves the Five Senses” books (Penguin Random House), which include depictions of deaf and blind children.

“Not everyone experiences their senses in the same way,” Spiro says. “So I told my editor, I really thought I should have somebody who lives this read through these and make sure everything was being portrayed accurately and fairly. She completely agreed.”

Faruqi has experienced sensitivity reading from multiple angles. For The Partition Project (HarperCollins/Quill Tree, 2024), Faruqi’s forthcoming middle grade novel, her editor asked Faruqi to find a sensitivity reader regarding a secondary character of Vietnamese heritage. For her biography collection The Wonders We Seek: Thirty Incredible Muslims Who Helped Shape the World (HarperCollins/Quill Tree, 2022), her editor hired the reader. Faruqi made several changes based on feedback. “It made those biographies much stronger,” she says.

However, Faruqi, a Muslim American woman, has also had negative experiences. A publisher hired two readers of Faruqi’s own ethnicity and heritage to read one of her manuscripts. Their criticisms did not ring true to her own experiences, and she was forced to defend her editorial choices.

“You can’t just tell me this is not correct, because this is my experience,” she says.

Faruqi still defends sensitivity reading as an essential part of the editorial process. “The biggest use or value is for authors writing outside their lane, outside of their group,” she says.

Still, some authors find value in hiring sensitivity readers for identities they share. Malia asked her editor at Beaming Books to hire them for “Infinity Rainbow Club,” a chapter book series about five neurodivergent children who form a club at their elementary school, even though Malia and the characters have the same identities.

“My neurodivergent identity didn’t mean I knew everything about neurodivergence—or that I couldn’t be insensitive either,” she explains.

Malia made significant changes to Violet and the Jurassic Land Exhibit based on that feedback. The revisions made it stronger, she says.

Andrew Sass, an author and sensitivity reader, shares Malia’s point of view. “Even when an author’s identity, disability, or heritage aligns with the character in question, I’ve found that a sensitivity reader can be helpful to obtain a second opinion,” he says. “Many experiences exist on a spectrum, so finding another set of eyes rarely hurts to provide further insight and nuance.”

|

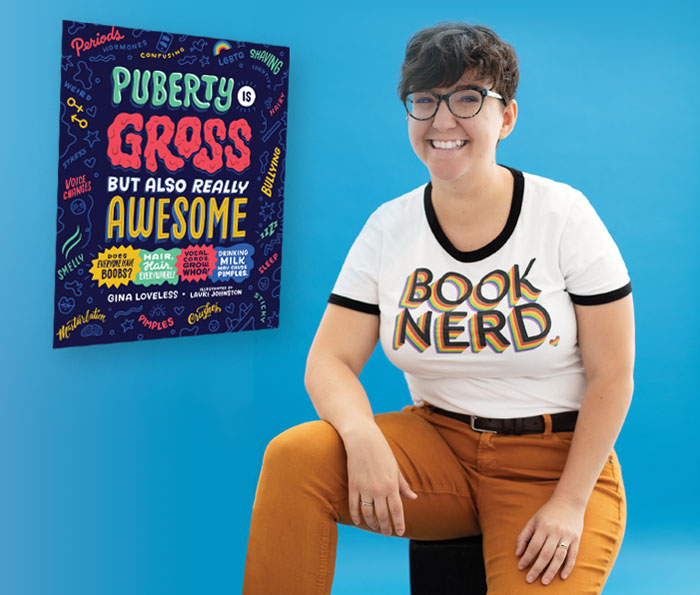

Author Gina LovelessPhoto by Aliza Schlabach Photography |

Word by word

Most sensitivity reads consist of in-text comments and an in-depth editorial letter that links to outside sources and opinions. Hannah Gomez, senior editor of cultural accuracy and sensitivity editorial services at Kevin Anderson & Associates, which provides ghostwriting and editorial assistance, says, “Pretty overwhelmingly, [authors] come back and say,‘I’ve learned about writing, about craft, about X group or experience, and I feel like a better writer.’”

Author Gina Loveless’s editor at Random House recommended a reader for Puberty Is Gross, But Also Really Awesome (Rodale/Random, 2021). While the editor hired a trans woman, Loveless also wanted the perspective of a nonbinary person and hired Sass.

“They were instrumental in some of the language used in the book,” she says.

When to bring in readers depends a lot on the manuscript. “The wrong time is, ‘This is already in galleys; can you look at this please?’” says Gomez.

Regarding her own books, Loveless thinks readers should be brought in early, in case extensive edits are needed.

“It can stand to be a little later if it’s about a minor character,” adds Gomez. “Some people have come to me to just talk about ideas and concepts for books or characters before they started writing, and I think that’s a smart approach. Otherwise, I would say, [review it when] other revisions are happening. If your editor is doing their big round of editing, you may as well send it to someone else too.”

A non-diverse editorial team may inadvertently overlook issues. “Sometimes you as an author are so close to the story that it’s hard to pick out some glaring issues,” says Faruqi. “But if nobody else on your [editorial] team, especially for a marginalized identity, is part of that [community], nobody else can be like, ‘Hey, wait a minute.’”

“This is not just a matter of assuaging hurt feelings or ‘taking offense,’” adds Beacom. She has seen how “inauthentic media representation can seriously impact deaf people’s everyday lives.”

For example, “The common trope of a deaf person who can lip-read flawlessly contributes to hearing people refusing to provide ASL interpreters for deaf people, even when the stakes are literally life and death, like law enforcement or medical situations,” Beacom says.

Addressing criticism of the process, Olds says, “There’s this strange image of sensitivity readers as an angry group of people who are out there trying to ruin author’s lives, but the reality couldn’t be further from the truth. Sensitivity readers love books, they love authors, and they genuinely want to help.”

And readers deserve to see authentic and nonharmful representation in their books. “Having sensitivity readers doesn’t necessarily keep anyone from getting it wrong,” Malia says. “But having them makes it a lot more likely that they will get it right.”

Margaret Kingsbury is a disabled writer, editor, and teacher.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!