Gaining Ground? Diversity in Publishing

Progress toward a more racially diverse publishing workforce has been slow. Publishing leaders face political and economic changes that may make further progress harder.

|

Illustration and SLJ February Cover (see below) by Jessie Lin |

When Stacey Barney started her career in publishing 23 years ago, she was one of only a few Black people in editorial roles. “I think you could likely count us on one hand,” she says, referring to all of publishing, not just her company. “Maybe there was one more finger.”

|

Stacey BarneyPhoto courtesy of Stacey Barney |

Though she and other Black editors followed in the footsteps of earlier pioneers, such as Charles Harris, who in 1986 founded Amistad Press, an adult imprint focused on Black authors, and editor and literary agent Marie Brown, progress toward a more racially diverse publishing workforce was slow. And it continues to be. “Slow but immense,” says Barney, who is now an associate publisher at Penguin Random House (PRH). “Also not enough at the same time.…A lot of different states of progress can exist at the same time.”

That tension—between visible progress and the need for more—applies to more recent history, as well. In 2020, as America dealt with a racial reckoning spurred by the killing of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, publishers vowed to diversify their workforces. According to the Lee & Low Diversity Baseline Survey, that commitment made some difference. From 2019 to 2023, the number of white people in publishing decreased from 76 percent to 72.5 percent, the survey found. The shift was driven by an increase in biracial and multiracial respondents from 3 percent to 8.4 percent. Most other racial groups saw little change, except for Latinx respondents, whose numbers declined from 6 percent to 4.6 percent.

For Jason Low, publisher of Lee & Low Books and coauthor of the survey, the top-line number of publishing becoming less white marks “a tangible through line that’s going in the right direction, and shows a commitment on behalf of publishers to hire inclusively.”

[Also read: Another Kid Lit Imprint Lost with the End of Algonquin Young Readers]

Andrea Davis Pinkney, vice president and executive editor for trade publishing at Scholastic and an author of nearly 50 children’s books, agrees that publishing has trended in a positive direction since 2020. “The good news is that the publishing community has started to develop a blueprint for progress,” she says. But she also cautions that progress is a marathon, not a sprint. “In 2020 everybody sprinted to hire diversity candidates, and…you can’t sustain a sprint for five years. We’re now seeing as a publishing community that we need to be in it for the long term. This takes stamina, consistency, intentionality, strength, and commitment.”

Pinkney and others working in children’s publishing say that staying in the race requires a focus on retention, hiring diversely across departments, and diversifying executive offices. But a marathon is never easy, and even as they push forward, publishing leaders face political and economic changes that may make progress harder, from political backlash to declining sales and book bans.

|

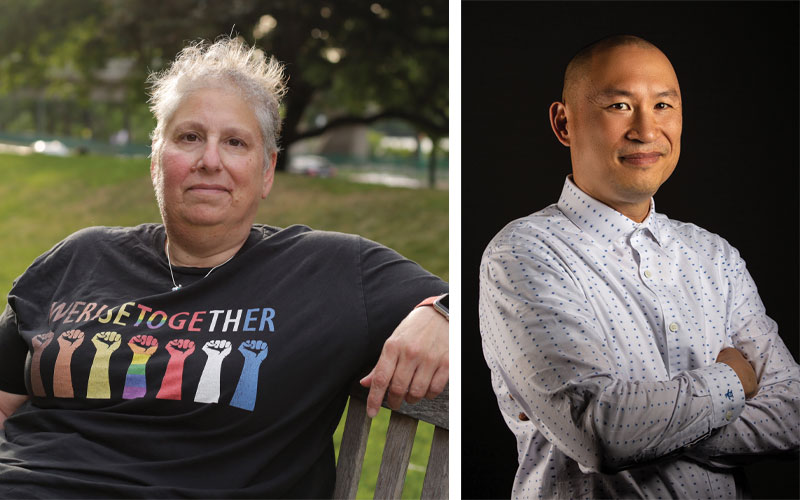

From the left: Laura Jiménez, Jason Low |

DEI backlash

Almost 40 years ago, Wade and Cheryl Hudson started Just Us Books as Black parents who wanted more books that reflected their children’s heritage and lives. Like Barney at PRH, Wade Hudson appreciates how the landscape has changed throughout his career. In the last 15 years, in particular, he has seen the ranks of people and organizations advocating for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the industry grow.

Agent Stefanie Sanchez Von Borstel is a board member for one such group, Latinx in Publishing, which organizes professional development and networking programs. “When I started in publishing, there was nothing like this at all. It was really, really hard to stay motivated [and] connect with others,” says Von Borstel, who cofounded Full Circle Literary in 2005. She notes that grassroots DEI work can add more to the plates of people of color, especially when publishers don’t invest in their own programming, “but I also hear again and again that it feels like such an important sense of community…and so I think it’s helping to keep people there.” Groups like We Need Diverse Books, People of Color in Publishing, and Latinx in Publishing have built connections and advocated for change.

|

L to R: Just Us Books founders Wade and Cheryl Hudson with their children, Katura Hudson, the company’s marketing manager, and Stephan Hudson, design managerCourtesy of the Hudson family |

Greater connection and visibility can attract unwanted attention, though. Wade Hudson says that history shows us that when people unite for change, “those who disagree with it…start to push back.” He recalled seeing negative online comments from some white educators and librarians as more people of color started winning major literary awards a decade ago. Fast-forward to now, when backlash to DEI initiatives has gotten louder and more organized across industries. In 2023, the Supreme Court ended race-conscious admissions in higher education. Following that decision, conservative groups began targeting corporate DEI programs with lawsuits. In November 2024, after Donald Trump’s election win, Walmart, the nation’s largest private employer, announced a major rollback of its DEI policies.

“These folks who organized this crusade against what they call ‘wokeism,’ they feel emboldened now and the election put the wind behind their sails,” says Hudson. “It means that they will be able to put pressure on corporations, whether they are publishers, or book distributors, or whatever, to think twice about advancing equity, advancing inclusion, advancing diversity, and even those who had taken a position that that’s what their company was about are starting to reassess now.”

The political challenges to DEI efforts across industries coincide with a downturn in sales for children’s books, and an onslaught of demands to remove books featuring characters of color and LGBTQIA+ characters from schools and libraries. According to Von Borstel, Latinx in Publishing couldn’t offer its publishing fellowship this year because it couldn’t secure publisher funding.

“Our work really is cut out for us,” says Hudson. But he believes that everyone involved in children’s publishing, from editors to authors to librarians, is up to the task. “Even if it seems difficult to move the needle, we’ve still got to fight to move the needle.”

Retention and support

Publishing’s 2020 wave of diverse hiring was not its first. But after past tides, Pinkney says, “we invited a lot of people in, but the retention wasn’t there.”

Many factors can lead to attrition, including low pay, limited paths to advancement, and workplace racism. In a 2018 survey of 200 publishing professionals conducted by People of Color in Publishing and Latinx in Publishing, 73 percent of respondents said they had experienced microaggressions at work, and 61 percent said they modified their speech, dress, hair, or other characteristics to fit into the workplace culture.

“As we move forward as a publishing community, we need to ask, are we ensuring that those people we hired in 2020 feel empowered, included, inspired?” says Pinkney. “Have we given them the tools to stay in the race and to succeed?”

Pinkney says that employee resource groups (ERGs) have been a “game changer” for this purpose at Scholastic. According to a document shared by a company spokesperson, the publisher boasts 14 ERGs, which allow employees to build community through shared identities and experiences, such as religion, race/ethnicity, or veteran status. In addition to connecting colleagues with one another, the ERGs organize community service activities.

Pinkney is on the leadership team for an ERG for women of color in leadership. “That’s a place where hires of color, women, really anybody can come, [and] we’re saying we’re here to support you.… We’re here to be your GPS to guide you on this journey and to give you actionable steps, strategies, techniques, support, mentoring, sponsorship, so that you can stay here with us,” she says.

Jennifer Baker, a 20-year publishing veteran and author who hosts the Minorities in Publishing podcast, says that avenues to advancement in publishing aren’t always clear. “What is the trajectory for you to get to where you need to be? I think that line moves a lot depending on where you are.” To retain employees, managers must provide clear and consistent pathways to advancement, along with the requisite training, Baker says.

Pay can also be a hurdle to retention. Barney says that when she started her publishing career, she took a pay cut from a $60,000 teacher’s salary to $19,000 as an editorial assistant. Starting salaries have increased in recent years—PRH recently bumped its base pay to $51,000, according to Publishers Weekly —but so has the cost of living, especially in publishing’s primary hub of New York City.

Von Borstel says that relocation expenses have prevented some members who participated in Latinx in Publishing’s programs from accepting entry-level jobs in the industry.

|

Andrea Davis PinkneyCourtesy of Scholastic |

Diversity across departments

Baker experienced publishing’s 2020 rush to diversify in multiple ways. That year, several heads of imprints approached her about editorial jobs, and she inked a book deal for her young adult debut, Forgive Me Not (Nancy Paulsen, 2023), which features a Black teen navigating the juvenile justice system. But Baker also saw the commitment to diversity wane not too long after. Several Black women who stepped into high-profile roles at various publishers in the diversity push have since resigned, been dismissed, or been laid off. Baker’s own position at Amistad was eliminated in 2022.

Books acquired by editors hired in 2020 and 2021 may only be coming out now, “when the economy looks incredibly different,” Baker says. That raises questions about how those books are being marketed and who’s in position to do that work. “If you invested a lot of money in the [book] advance, how much was invested in the promotion and sales? When the book comes out two or three years later, what does that look like? I’d be interested in that data,” she says.

Baker says that hiring diverse editors is only one piece of the publishing puzzle: “If you bring in Black editors, are you bringing in Black marketers, Black publicists, Black production people, Black designers? Are you sharing with a whole team that’s already overworked and understaffed?”

Editorial departments saw the biggest shift in racial makeup in recent years, according to the Lee & Low survey. Those roles decreased from 85 percent white in 2019 to 72 percent in 2023. Smaller declines occurred in sales departments (from 81 percent to 77 percent) and marketing and publicity (from 74 percent to 71 percent) over the same time period.

Barney agreed with Baker that companies need to be intentional about hiring diversely across departments. “[Editorial] gets the most attention because we’re responsible for the books that come into our pipelines,” she says. “But I don’t work in solitude.… Publishing is a team sport.”

To diversify other departments, Barney says that publishers and educators need to raise more awareness about the types of roles candidates can aspire to. She, for instance, first considered an editorial career during a book publishing course as an MFA student. That opened a door she didn’t previously know existed, but she didn’t learn about other aspects of publishing until she got into the business.

Laura Jiménez, an education professor at Boston University and co-author of the Lee & Low survey, says that executive leadership also needs attention. Executives were 78 percent white in the 2019 survey and just under 77 percent white in 2023—not a statistically significant change. “There really seems to be a serious ceiling effect in the executive levels,” Jiménez says. “They’re not the content creators, but they set the table, right?”

|

Jennifer BakerGaby Deimeke |

Standing together

In the fall, Pinkney moderated a panel at a DEI summit that brought together professionals from across the industry. She says that kind of communication must continue in the face of political and economic challenges. “DEI is an ecosystem [that] includes publishing houses, authors, agents, booksellers, advocacy groups. We have to stand together arm in arm and keep moving forward,” she says, adding that for those in children’s publishing, “every aspect of that [ecosystem] ultimately touches the child.”

Low says that the Diversity Baseline Survey has enabled conversations and decision-making that couldn’t happen without that data. He considered skipping the last survey cycle amid a hectic 2023, but he didn’t because people were asking for it. When Low first created the survey in 2015, he took inspiration from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s diversity statistics on representation in children’s books. “It took decades for the industry to rally around diverse books,” he says. “Leaders have to prevent that progress from slipping away.”

Despite the challenges, Barney remains hopeful that incremental change will continue to add up. “I’ve seen a lot of highs and lows, but where I am now, it’s a place I probably could not have imagined when I started,” she says. “In the next 23 years, I can’t imagine how different and hopefully wonderfully diverse publishing will be from this new generation who’s now just starting out.… They are so powerful in their own voice, asking for things I would have been afraid to ask for and getting it. That’s awesome. So maybe their change won’t be quite as incremental.”

Kara Newhouse is an award-winning journalist who has covered education and other topics for print, digital, and audio outlets.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!