Crucial Conversations: It’s Never Too Early To Talk About Race

Research shows that preschoolers naturally categorize people by race, can be conscious of social stereotypes as early as age six, and naturally attribute positive traits to their own ethnic or racial groups.

|

©Tom Williams/Associated Press |

A week after the murder of an African American man, George Floyd, at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, Nickelodeon, the children’s media network, aired a message.

For eight minutes and 46 seconds (the amount of time a police officer had his knee on Floyd’s neck as he lay helpless and then lifeless on a public street), viewers saw a black screen containing three words in white text: “I can’t breathe.” The only sound was that of someone breathing.

On social media, some praised Nickelodeon for forcing a conversation about racial injustice. Others argued that a children’s network was not the right platform for a “scary” ad. Nickelodeon responded: “Unfortunately, some kids live in fear every day. It is our job to use our platform to make sure that their voices are heard and their stories are told.”

Amid mounting racial injustice and nationwide protests calling for change, the commercial illuminated questions concerning when and how to teach children about race. It was also a call for parents and educators to embrace anti-racism.

|

SLJ montage. Photo source: Phynart Studio/Getty Images |

“Children often become aware of these events in the news and have concerns and questions,” says clinical psychologist Ann Hazzard, coauthor of the children’s book Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice.

“When we read and discuss the book, early elementary children are engaged and appropriately concerned about injustice, but not traumatized,” she says. “It’s the adults who are intimidated by approaching the content.”

Though Hazzard believes that children should be shielded from graphic images or inappropriate details of violent incidents, she and many experts agree that discussions with children about race and racism can and should begin early.

This is in part because research shows that preschoolers naturally categorize people by race, children can be conscious of social stereotypes as early as age six, and kids naturally attribute positive traits to their own ethnic or racial groups.

Additionally, Hazzard says that “without context and corrective information from adults, white children can develop bias from exposure to media stereotypes and disparities.”

Despite these rationales, parents and educators often avoid talking about race for fear of saying the “wrong” thing. “But silence can communicate that race is a taboo topic or signal a lack of concern about the racial status quo,” Hazzard explains.

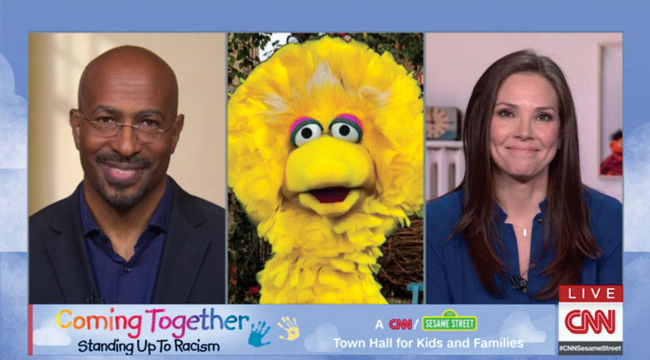

In a CNN/Sesame Street Town Hall about racism, psychologist and educator Beverly Daniel Tatum, author of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?, says the goal is “to talk in a warm and inclusive way about differences that exist in different people.”

|

The CNN/Sesame Street Town Hall |

For example, if a child describes another child’s skin color in a derogatory way, a parent could say that all people have different, beautiful skin colors or explain that skin colors come from different amounts of melanin.

Sometimes, however, parents and educators avoid addressing differences and instead teach children to be “colorblind” (i.e., disregard ethnicity or race). Some consider this counterproductive.

“If you can’t talk about [race], you can’t understand it, much less fix the racial problems that plague our society,” says clinical psychologist Monnica T. Williams in Psychology Today.

In the article “Colorblind Ideology Is a Form of Racism,” Williams writes that “because [people of color] often encounter difficulties due to race, colorblindness creates a society that denies negative racial experiences, rejects cultural heritage, and invalidates unique perspectives.”

Janet R. Damon, library services specialist for Denver Public Schools, agrees. In family engagement sessions, she encourages parents concerned about “messing up and accidentally raising a racist” to model their truths to their children.

This could sound like, “You know, when I was young, we were taught not to talk about race.” Or “I love your grandfather, but he said or did things when I was a kid that I don’t agree with and I want our family to do things differently,” she says.

In approaching these conversations, clinical psychologist Afiya Mbilishaka says that “parents should identify ways that the color spectrum impacts their challenges and privileges.” For Black families, this often means not “sugarcoating” stark realities of racism.

“Black families talk to their children about race for preparation and protection,” Mbilishaka explains. “To function in a world that does not value Black lives, Black parents want their children to know when racism is happening and how to cope with it.”

To counteract negative portrayals and instill confidence, Mbilishaka suggests that parents of color focus on culture and expose children to positive images and media. Hazzard cautions that content used to educate children about race should not focus exclusively on people of color struggling against oppression.

“Library collections should include books about diverse individuals having typical childhood experiences,” Hazzard says. “Art, music, and science lessons can cover the contributions and cultures of diverse people—and not just during Black History Month!”

|

Doloves/Getty Images |

Actions speak louder than words

Talking to children about race is one, albeit crucial, aspect of preparing the next generation to be good citizens. Modeling anti-racism (i.e., being actively engaged against racism in all aspects of life day-to-day) is another.

Research has long shown that what adults do is sometimes more impactful for children than what adults say. So adults who actively engage in cycles of learning, listening, and talking about anti-racism may be more effective at teaching children to be anti-racist.

For educators, Hazzard says, embracing anti-racism might involve ensuring diversity in books that they and students read and teaching age-appropriate lessons on racial injustice and history that do not gloss over painful truths.

Beyond “the rush [she sees] to push diverse book collections and book talks,” Damon suggests that librarians advocate for local equity initiatives or support scholarship fundraisers for diverse organizations.

Anti-racist policies are also important. “Teachers can contribute to school and district policy reform efforts to reduce racial disparities in educational opportunities and school discipline,” says Hazzard.

Overall, Hazzard believes that teaching children about race and racism is a process. “Addressing bias takes openness and courage, but…it’s not just one conversation,” she says.

Damon concurs. “This important work also requires self-reflection and humility.....We all bring fear, childhood trauma, and trepidation to these conversations.”

As a result, and to better understand the harmful impacts of systemic racism, privilege, and unconscious bias that are pervasive in education, parents and educators must reflect on their own (sometimes painful) race-related experiences. The resulting awareness can make them more powerful role models for children.

Meanwhile, in the wake of remarkable protests for racial justice, some families tuned in to the CNN/Sesame Street Town Hall to get guidance on anti-racism from children’s media characters like Big Bird and Elmo.

Jeanette Betancourt, senior vice president of social impact for Sesame Workshop (the nonprofit organization behind Sesame Street), also offered insight.

“In our house, we often say that the hard conversations are the most important ones,” she said during the Town Hall. “This is an opportunity to talk, in everyday moments, about similarities and differences and to take advantage of the diversity that surrounds you—but to have these conversations early on in a way that sets a foundation and lasts for a lifetime of awareness.”

Kelley R. Taylor has covered trauma-informed librarianship, web accessibility, and restorative justice for SLJ.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!