Teaching Nonfiction? What You Need To Know About the Differences Between Expository and Narrative Styles

Effective teaching of nonfiction texts requires a keen understanding of the differences in formats and writing styles. Award-winning nonfiction author Melissa Stewart offers a deep dive into the differences between two types of nonfiction, expository and narrative, offering educators comparative texts, specific examples, and tips on teaching and connecting with young readers.

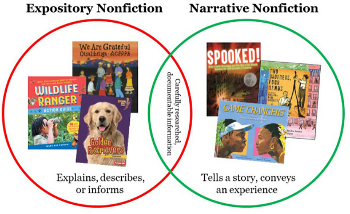

It's vital that teachers and librarians understand the differences between the two nonfiction writing styles: expository and narrative.

It's vital that teachers and librarians understand the differences between the two nonfiction writing styles: expository and narrative.

This article compares expository nonfiction passages from my book Ick! Delightfully Disgusting Animal Dinners, Dwellings, and Defenses to narrative passages on similar topics from three books I admire: Honeybee: The Busy Life of Apis mellifera, written by Candace Fleming and illustrated by Eric Rohmann; Flying Deep: Climb Inside Deep-Sea Submersible ALVIN, written by Michelle Cusolito and illustrated by Nicole Wong; and You’re Invited to a Moth Ball: A Nighttime Insect Celebration, written by Loree Griffin Burns and photographed by Ellen Harasimowicz.

Read also: Understanding and Teaching the Five Kinds of Nonfiction

Comparison 1: A look at honeybees

As you view this double-page spread about honeybees from Ick!, you’ll notice that it’s illustrated with photographs, including a truly astonishing close-up of a bee with a drop of nectar. The spread has a variety of text features, including main text, captions with fascinating facts and figures, a stat stack for kids who love data, a spit-tacular sidebar, and a factoid that compares honeybees to archerfish—another animal that relies on spit for its dinner. Here’s the main text for this spread:

"What’s in Your Honey

You probably know that honeybees make sweet, sticky honey. But do you know how? The process might surprise you.

1. A field bee—a honeybee that leaves the hive to collect nectar— sucks up thin, runny liquid from dozens of flowers. She swallows some of the nectar and stores the rest in her honey sac.

2. Back at the hive, the field bee upchucks the nectar, and a house bee slurps it into her honey sac. Little by little, the house bee regurgitates the sugary stuff. As she rolls it around in her mouth, it mixes with her spit. The nectar warms up and thickens.

3. After the house bee spreads the mixture along honeycomb cells inside the hive, her sisters fan their wings over the cells. Water evaporates, causing the liquid to thicken even more.

4. After about five days, most honey is ready to eat. It’s nutritious and delicious!"

In all the books I write, my goal is to share the beauty and wonder of the natural world with children. My hope is that Ick! will fill young readers with excitement and awe, as they discover how animals get food, make homes, and defend themselves in ways that might seem pretty yucky to us. For example, who knew that bees use spit to make honey?

A numbered list is a great way to convey this information clearly and succinctly to curious kids who are excited to soak up ideas and information about the world. The linear progression helps young fact-loving minds digest and remember the content, so they can quickly and easily share the tantalizing tidbits with their family and friends—something many kids love to do.

To make the expository description engaging, I employed a casual, playful, conversational voice and included strong, precise verbs, alliteration, and a bit of rhyme.

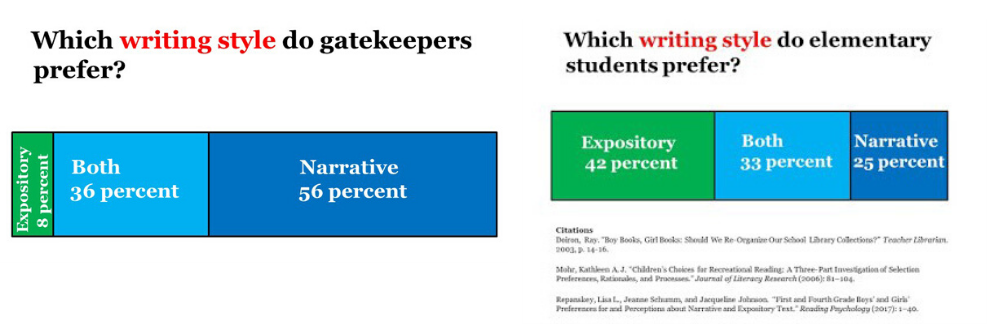

This way of presenting the material seems natural to me. It appeals strongly to my analytical mind. According to a growing body of research, many children think like me. Even though the majority of educators prefer stories and storytelling, 42 percent of the students they serve would rather read expository nonfiction, and another 33 percent of children enjoy both writing styles equally.

Expository-loving “info-kids” read with a purpose—to soak up facts, ideas, and information about topics they find fascinating. They want to understand the world, how it works, and their place in it. They want to learn about the past and the present so they can envision the future stretching out before them.

To feed all children a steady diet of the books they crave, classroom and library collections need plenty of nonfiction—both expository and narrative. While experts recommend a 50-50 mix of fiction and nonfiction with two-thirds of the nonfiction having an expository writing style, research shows that classroom collections currently include just 17 to 22 percent nonfiction overall and only seven to nine percent expository nonfiction.

Fleming and Rohmann's Honeybee: The Busy Life of Apis mellifera is a magnificent narrative nonfiction title that pairs perfectly with the honeybee passage in Ick!

The key element of narrative nonfiction is scenes, which give readers an intimate look at the world and people (or insects) being described. These scenes are linked by expository bridges that provide necessary background information while speeding through parts of the true story that don’t require close inspection.

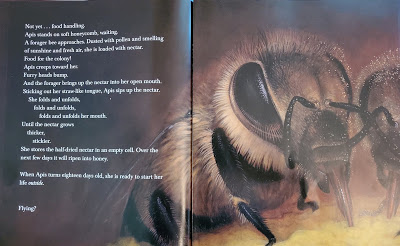

Here’s a spread from Honeybee with some of the same information as the passage from Ick!

Instead of a numbered list, Fleming has written a compelling scene that’s illustrated with Rohmann's stunning art. Here’s the text:

"Apis stands on soft honeycomb, waiting.

A forager bee approaches. Dusted with pollen and smelling

of sunshine and fresh air, she is loaded with nectar.

Food for the colony!

Apis creeps toward her.

Furry heads bump.

And the forager brings up the nectar to her open mouth.

Sticking out her straw-like tongue, Apis sips up the nectar.

She folds and unfolds,

folds and unfolds,

folds and unfolds her mouth.

Until the nectar grows

thicker,

stickier.

She stores the half-dried nectar in an empty cell. Over the

next few days it will ripen into honey."

Fleming is truly a master of rich, luscious language. I love her use of strong, precise verbs; alliteration; repetition; and imagery. Notice how her text breaks force you to pause at just the right moments.

According to Fleming, writing nonfiction with a narrative style comes naturally to her. "I’ve always preferred a story with scenes and characters and emotional weight. And let’s face it; anything that comes naturally has its advantages.“

"When I began this project," Fleming continues, "the plight of bees was foremost in my mind. I wanted to write a book that would engage and enlighten kids, as well as help them recognize the importance of this extraordinary creature. Above all, though, I wanted to spur young readers to action. But action requires empathy. I wanted my readers to care, truly care, about honeybees. And I didn’t think fascinating facts and startling statistics alone would be enough to elicit that kind of emotion. So I turned to narrative.

I wrote a birth-to-death story—a biography—of one bee, following her every movement from the day she emerges into her hive until 35 days later when, tattered and exhausted, she falls to the ground. I emphasized her struggles, heightened tension and suspense, and intentionally created an emotional punch.

A narrative style is the best way I know of distilling a story and getting to the heart of it. I chose narrative with the goal of the writer’s profession: readers finishing the story and maybe, just maybe, caring.

The biggest challenge [of writing a narrative] is staying within the nonfiction fence. [Facts] have to be woven thoughtfully and artfully into the text, so they feel like a seamless part of the telling. While I want kids to cheer, gasp, and cry for Apis mellifera, I cannot anthropomorphize to achieve this goal, and I cannot make up anything. Every detail in the book has to be documented. It has to come from a reliable source.”

By comparing this response from Fleming to my comments above, it’s easy to see how a writer’s natural affinity for a particular writing style as well as her purpose for writing a piece play critical roles in how she decides to present the material. That’s why it’s so beneficial to share book pairings with students.

By reading a variety of related passages, students can gain a deeper understanding and appreciation for the topic as well as all that the wonderful world of nonfiction has to offer. Children can also gain important insight into the kinds of texts they enjoy reading and writing the most.

Comparison 2: Journey to the deep sea

Next, let’s look at two passages about amazing deep-sea creatures—one from Ick! and one from Cusolito and Wong's Flying Deep: Climb Inside Deep-Sea Submersible ALVIN.

By examining those two texts closely, you can gain a more solid understanding of:

- the differences between the two writing styles (narrative vs. expository),

- when it makes sense to use each of these writing styles,

- how each type of writing appeals to particular subsets of children, and

- how sharing expository and narrative passages together provides powerful pedagogy.

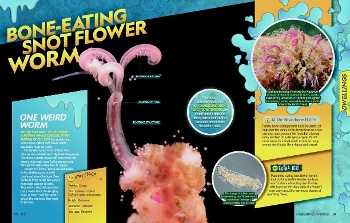

Here’s a spread from my expository nonfiction book, Ick!

Even though there are a lot of text features, readers don't feel overwhelmed because the design helps them navigate across the pages, from the yellow headline to the central photo to the main text on the left to the secondary text features on the right.

Here’s the main text for this spread:

"One Weird Worm

Would you want to live inside a rotting whale carcass at the bottom of the sea? You would if you were a bone-eating snot flower worm. Yep, that’s really its name.

The females spend most their lives attached to a whalebone. Frilly, flowerlike plumes rise above a snotty mucus ball that covers the worm’s main body tube. As the plumes wave through the water, they take in oxygen.

The worm's 'roots,' which are embedded in the whalebone, ooze acids that break down the bone. Then bacteria living inside the worm’s main body tube go to work. They absorb fats, oils, and other tasty treats from the decaying bone, so they—and the worm—get all the nutrients they need to survive."

From the moment I began thinking about Ick!, I knew it would have an expository writing style. Expository nonfiction is generally the best way to present narrowly-focused STEM concepts, such as how an animal’s unique body parts or behaviors help it survive in the world. It’s also a good choice for sharing information in short blocks of text accompanied by lots of visuals and a range of text features.

The challenge of writing expository nonfiction is choosing a great hook, a compelling text structure, and just the right voice. Since gross animals are a powerful hook in and of themselves, that was the easy part of conceiving this book. I had lots of intriguing animal examples, so I knew a list text structure would work well. And the content just cried out for a playful, conversational voice that would delight as well as inform.

Author Cusolito took a different approach in Flying Deep, a fantastic narrative nonfiction title that puts young readers in the pilot’s seat for a thrilling journey to a hydrothermal vent far below the ocean’s surface.

Like the bone-eating snot flower worms in Ick!, the deep-sea denizens in this book are nothing like the creatures we see on land. The environment is so exotic that young readers can’t help but be intrigued.

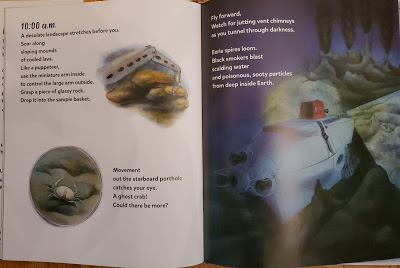

Let’s take a closer look at two spreads from the book:

"10:00 a.m.

A desolate landscape stretches before you.

Soar along

sloping mounds

of cooled lava.

Like a puppeteer,

use the miniature arm inside

to control the large arm outside.

Grasp a piece of glassy rock.

Drop it into the sample basket.

Movement

out the starboard porthole

catches your eye.

A ghost crab!

Could there be more?

Fly forward.

Watch for jutting vent chimneys

as you tunnel through darkness.

Eerie spires loom.

Black smokers blast

scalding water

and poisonous, sooty particles

from deep inside Earth.

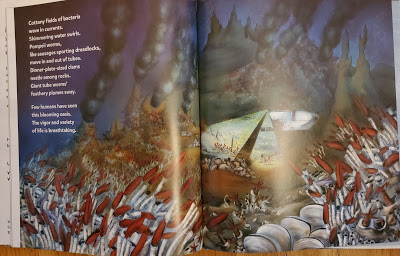

Cottony fields of bacteria

wave in currents.

shimmering water swirls.

Pompeii worms,

like sausages sporting dreadlocks,

move in and out of tubes.

Dinner-plate-sized clams

nestle among rocks.

Giant tubeworms’

feathery plumes sway.

Few humans have seen

the blooming oasis.

The vigor and variety

of life is breathtaking."

Notice Cusolito’s use of second-person narration (“stretches before you,” “catches your eye”), similes and metaphors, and precise word choice. She varies sentence length to build drama, and her imagery is spot-on. The craftsmanship behind this book is undeniable.

“To write in a narrative style,” says Cusolito, “you need the basics of a story: beginning, middle, and end. Biographies tend to have this built-in, but many STEM topics will not work in a narrative style.”

By framing her book as an undersea adventure, a journey to a hidden world beneath the waves (which has a built-in story arc), the author found her way to a narrative style. She explains, “I was out for a walk when the first line popped into my head: ‘Imagine you’re the pilot of ALVIN, a submersible barely big enough for two.’ (Note: it fits three. My memory was wrong.) I thought, ‘Whoa! That's good!’ I reached to my back pocket for my notebook, but I had forgotten it. [Luckily] it dawned on me that I had another tool in my pocket I could use—a smartphone with a Notes app. I sat down beside a pond to type that first sentence and more came flooding out. I typed wildly, with one finger, trying to capture everything.

When I looked up 30 minutes later, I had a 500-word draft. By putting the kid reader in the pilot seat for a typical dive day, I had found the heart and structure of my story.

Once I decided on using the structure of a dive day [a narrative with a sequence text structure], many of the decisions were made for me...so I was able to [focus on] word choice and rhythm.”

By comparing this response from Cusolito to my comments above, it’s possible to identify some of the reasons an author decides to use either expository or narrative nonfiction in STEM-themed books. For example, expository nonfiction is the best choice for books that explain or describe widely-accepted science knowledge or concepts, while narrative nonfiction is a better choice for titles that focus on the role of humans in making scientific discoveries. Narratives can explore how scientists carry out investigations or the nature of scientific inquiry.

Comparison 3: What’s for dinner?

Finally, let’s compare two loosely connected passages that include information about what butterflies and moths eat. One comes from Ick! and the other is from Griffin Burns and Harasimowicz's You’re Invited to a Moth Ball: A Nighttime Insect Celebration. My hope is that comparing these two texts will further assist you in differentiating the two writing styles and in understanding the best situations for using each kind of text.

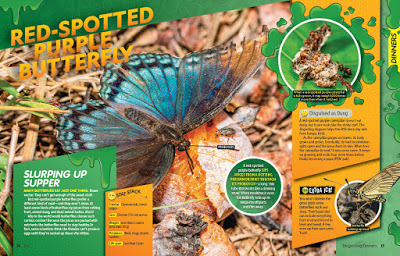

Here’s the red-spotted purple butterfly spread from Ick!

Like the other spreads in this book, it’s illustrated with photographs, including a large close-up image of a butterfly gorging on juices from a rotting persimmon fruit. And it has a variety of text features, including captions with facts and figures, a stat stack for kids (and adults) who love data, a sidebar about red-spotted purple caterpillars (which look a whole lot like bird poop), and a factoid that describes even more surprising butterfly food choices, from mud and blood to sweat and urine.

Even though there’s a lot to explore on this spread, the design helps readers navigate the elements. While some narrative lovers might feel a bit overwhelmed by this layout, info-kids will be excited by the cornucopia of choices.

Here’s the main text for this spread:

"Slurping Up Supper

Many butterflies eat just one thing—flower nectar. They can’t get enough of the sweet stuff.

But red-spotted purple butterflies prefer a different kind of meal. And they aren’t alone. At least seven kinds of butterflies sip juices from rotting fruit, animal dung, and dead animal bodies. Blech!

Why in the world would butterflies choose such curious cuisine? Because the juices are packed with nutrients the butterflies need to stay healthy. In fact, some scientists think the females can’t produce eggs until they’ve sucked up these vile vittles."

Since Ick! focuses on animals that rely on gross stuff like pee, poop, vomit, and rotting carcasses for food, building materials, or defense strategies, my goal on this spread was to describe the strange and surprising range of foods that butterflies, especially the red-spotted purple butterfly, eat. To make the expository text engaging, I employed a casual, playful, conversational voice and included a healthy helping of strong, precise verbs and alliteration along with a dash of onomatopoeia.

While I sincerely hope that kids will be as excited to read Ick! as I was to write it, I recognize that it may not be a good fit for every young reader. And that’s why I’m thrilled that Griffin Burns and Harasimowicz created You’re Invited to a Moth Ball, a narrative nonfiction title that features kids joyfully observing an incredible variety of moths—an experience they won’t soon forget.

Moth Ball is perfectly suited for a narrative writing style because it conveys an experience.

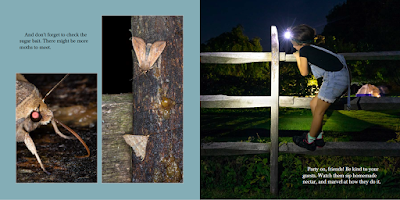

Let’s take a look at two spreads:

The first spread (top) features a group of children observing an incredible variety of moths attracted to a white sheet illuminated by a special light. Wow! And the second spread (which loosely connects to the food theme of the Ick! spread above) highlights why it’s useful to know an insect’s dietary preferences.

Here’s a closer look at Griffin Burns's text:

"The number of moths might be small at first. Be patient. On a warm night, moths become more active as the night gets darker and the hour gets later.

Some people never, not once in their whole lives, connect with moths this way. So take your time. Soak it all in.

And don’t forget to check the sugar bait. There might be more moths to meet.

Party on, friends! Be kind to your guests. Watch them sip homemade nectar, and marvel at how they do it."

There are so many things to love about the way this book is written. While direct address (“Be patient.” “take your time.”) can sometimes seem heavy-handed or even didactic, in this book, it contributes beautifully to the gentle, friendly, invitational voice. Even though the language is remarkably simple, each word has been carefully chosen to instill a sense of wonder and awe, which will undoubtedly inspire many young readers to begin planning a moth ball of their own.

After reading the book, I wondered what inspired Griffin Burns to write about a moth ball rather than a more general introduction to moths. I also wanted to know how and why she decided to employ a narrative writing style. Here’s what she had to say: “I’m one of those people who is naturally drawn to narrative. I never asked myself what would be the best writing style for a book about moths. Instead, I stumbled into a subject that was new and fascinating to me—moth watching, and I saw immediately that there was a beautiful and intriguing narrative ready-made—a moth watching party, or moth ball. Those two things convinced me that I wanted to make this book.

This is not a book that gives a reader everything they'll ever want to know about moths. Rather, it’s an invitation into the world of moths, a quick and (I hope!) intriguing look at a new subject. My fondest wish is that readers finish and do two things immediately: 1) hit the library for more books about moths and 2) start watching the moths in their own neighborhoods.”

According to Griffin Burns, one big advantage of writing a narrative is the built-in text structure. While writers of expository nonfiction have to carefully consider how they will frame their facts, narratives typically have a chronological sequence structure. “I didn't start by pondering how to organize all the moth facts,” the author explains. “Instead, my focus was entirely on telling a compelling moth story. I had to decide where to begin that story, where to end it, and how to get from one to the other.

Eventually, I decided I would host a moth ball and invite readers to come. That story starts with the book's title. I have readers arrive early, when it's still light outside, so that they can help me set up the party; that’s how they learn to attract moths. The story ends where so many great stories (and parties) do: bedtime.

This very simple story structure guided the way I conveyed moth facts. I couldn't just stick those facts anywhere, because I had to consider the party narrative. [There’s a] natural break in the party after the moth attractants were set but before the moths arrived. [That’s where] I tucked extra moth facts for readers.”

The importance of exposing students to both nonfiction writing styles

I hope that directly comparing expository and narrative passages will help educators see that two writing styles present information in different ways, and as a result, appeal to different kinds of readers.

Ultimately, we want all students to interact successfully with both expository and narrative texts, but developing the skills to do so takes time and patience and practice. That’s why it’s so important to meet young readers where they are by understanding and encouraging their natural preferences.

When school and public library collections feature a rich assortment of expository nonfiction, narrative nonfiction, and fiction titles, every child will be able to find books they connect with right now as well as books that can help them stretch and grow as they develop confidence as readers.

Melissa Stewart has written more than 180 science books for children, including the ALA Notable Feathers: Not Just for Flying, illustrated by Sarah S. Brannen; the SCBWI Golden Kite Honor title Pipsqueaks, Slowpokes and Stinkers: Celebrating Animal Underdogs, illustrated by Stephanie Laberis; and Can an Aardvark Bark?, illustrated by Caldecott Honoree Steve Jenkins. Her most recent title is Ick! Delightfully Disgusting Animal Dinners, Dwellings, and Defenses. Melissa maintains the award-winning blog Celebrate Science and serves on the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators board of advisors. Her highly-regarded website features a rich array of nonfiction writing resources.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!