Between Friends: Books Help Tackle the Tough Emotions that Go with Friendship

Getting real about the stormy, frustrating, and sometimes sad aspects of friendship can help middle schoolers navigate social interactions, research shows.

|

Getty Images/gradyreese |

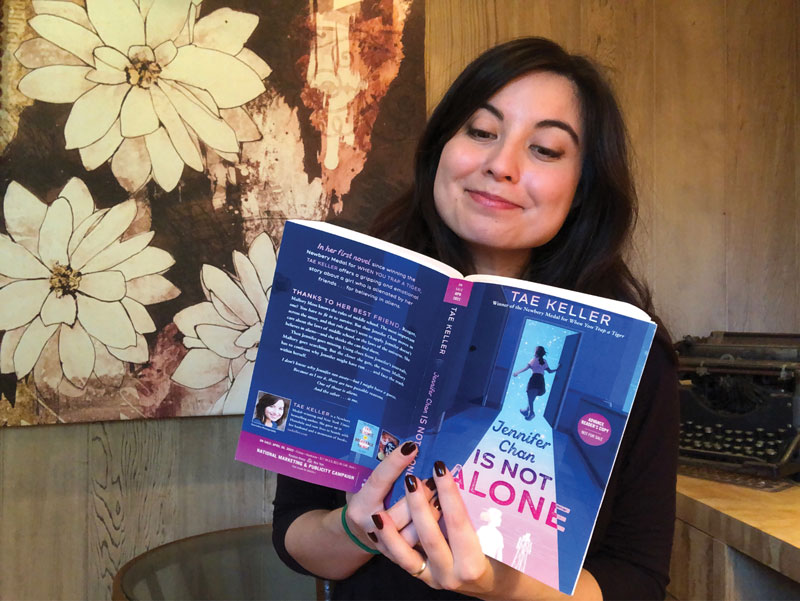

In the last day of school, a group of girls who had been targeting 12-year-old Tae Keller on social media chased her into a bathroom. They cornered her and started “telling me all these things about how I would never be anyone,” Keller says. They asked, “Who do you think you are?” Distressed and confused, Keller didn’t understand why they’d behave that way.

A reader, Keller was used to making sense of the world through books, and she looked to fiction for insight. But she couldn’t find a window into her classmates’ motivation. For years at school, Keller tried to make herself “smaller,” she says: “to dim myself down.” When she became a middle grade author, she set out to write the book she’d once sought—and reclaim that defining question of adolescence: “Who do you think you are?”

|

Tae KellerPhoto courtesy of Tae Keller |

Her novel Jennifer Chan Is Not Alone (Random, 2022) revolves around “the Incident,” where Mallory, whom Jennifer considers a friend, takes part in her bathroom ambush. In so doing, the book portrays friendships in a way that normalizes complexity and anguish.

Helping middle schoolers be real about the stormy, frustrating, and sometimes sad aspects of friendship, rather than idealizing affection between friends, can help them navigate social interactions, research shows.

“We can be afraid to recommend books to kids where friendships fall apart,” said Shauntee Burns-Simpson, associate director of the New York Public Library’s Center for Educators and Schools. “It’s really important for kids to see the challenges of friendship and realize that it’s not just them.”

When Keller was young, she read story after story featuring either “best friendships that are totally stable and perfect” or victimized social pariahs. Her own experience fell in between. Keller wanted readers to know that “everyone is figuring out who they are, so naturally your friendships will change....It’s not cause for total panic.” Yet when she tried to write, Keller couldn’t get into the tormentors’ heads. So she did something that “horrifies” the tweens who attend her readings: She DMed the people who bullied her on Instagram.

Her outreach produced Mallory, who mocks and excludes Jennifer without understanding the destructive impact of her actions. Mallory is afraid of losing status, of feeling small herself. She feels valued and supported by another tormentor and doesn’t want to let her down. That girl, in turn, has a difficult home life, and bullies because “there’d been nowhere else for her anger to go,” Keller writes.

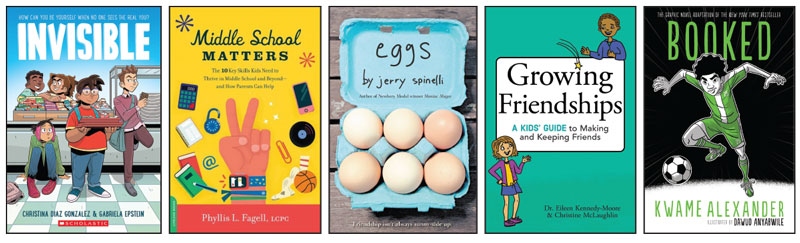

Unseen pressures are also a theme in the bilingual graphic novel Invisible by Christina Diaz Gonzalez and Gabriela Epstein (Graphix, 2022). Nico seems standoffish and haughty. In reality he has just been separated from his parents and worries he will experience homelessness. Still, he does his best to help a mother and daughter living in a van. But his classmates don’t know any of that: “That guy doesn’t care about anything or anyone,” Nico overhears one of them saying. Eventually, however, friendships form.

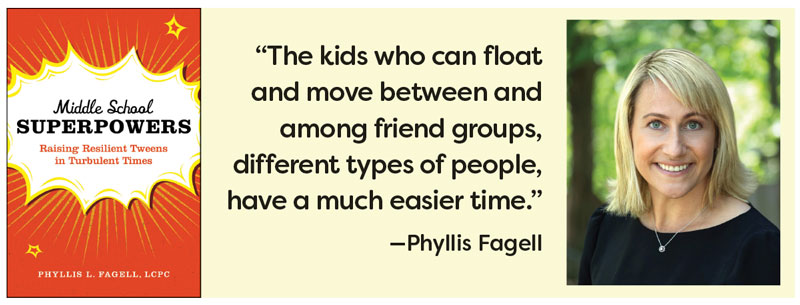

Such authentic stories and details help align literature with the reality of middle school friendship, says Phyllis Fagell, a school counselor in Washington, DC, and author of the books Middle School Matters (Da Capo, 2019) and Middle School Superpowers (Hachette, 2023).

A paper on a “Survival Analysis” of adolescent friendships revealed their mutability: Only about half of friendships survived a middle school year, and only one percent of seventh-grade friendships remained intact by senior year of high school. Additional research by UCLA psychology professor Jaana Juvonen and a colleague confirmed the pervasiveness of friendship churn in adolescence: Two-thirds of sixth-grade friends were either lost or gained over the course of a school year.

“These are very fragile, mercurial, nonreciprocal friendships,” Fagell says, noting that among sixth graders, 12 percent had nobody name them as a friend. Eighty percent of all students experience loneliness at school, a separate study showed.

|

Photo by Jonathan Blanc/The New York Public Library |

Then there’s the “best friend” ideal. Fagell hates the term. Middle schoolers often crave the kind of tight twosome they see in media. But in real life, “it’s a lose-lose,” she tells young people. “If you are the one in that dyad, you have put all your eggs in one basket. So if that relationship goes south you have no safety net, and at the same time everybody in [your] outer orbit is feeling like a third wheel, feeling left out.”

Research on cliques dispels any lingering impression that they’re typically a picture-perfect cluster of ride-or-die, equally situated buddies who stay tight for years. Cliques can be loose and porous, explains science journalist Lydia Denworth in her book Friendship (Norton, 2020). Friend groups often have an uneven power distribution. And they regularly collapse, which is why, in Fagell’s words, “The kids who can float and move between and among friend groups, different types of people, have a much easier time.”

Floating and moving can also include returning to the same person. In Jennifer Chan Is Not Alone, Mallory also forsakes her science-obsessed friend, Ingrid, but reconnects and repairs after realizing they share interests and values. Still, she feels “a hot flash of embarrassment” when her higher-status friend sees them together.

Fictional characters grappling with status can help readers learn to seek “right-fit friends for right now,” Fagell notes. They communicate that forming and keeping friends depends on similarity, a true concordance, not surface-level commonalities or an objective measure of appeal. With interests shifting and personalities developing, that means there’s always an opportunity to make a new friend.

“It’s really, really important for us to push that narrative,” said Burns-Simpson. “Books are supposed to be the windows and mirrors and sliding doors. Let’s make sure that we are giving stories that [do] that for friendship.”

A person doesn’t have to be flawless to be a good friend. The students in Invisible connect over a mission: helping a child who is struggling with homelessness. In Jerry Spinelli’s Eggs (Little, Brown, 2008), the odd-couple characters “seemed to get along. Maybe because he had a sourpuss to match hers.” And in John Cho’s Troublemaker (Little, Brown, 2022), the narrator knows his buddy Mike can be annoying. Mike also lied to him and got him in trouble for graffitiing church walls. But when Mike was really needed, he “stuck by me.”

Fagell encourages such fair-minded assessment, “because the worst situation is that you have nobody,” she says. And a single pal has significant value: There’s a huge difference in academic and psychosocial outcomes between friendless adolescents and those with just one friend.

|

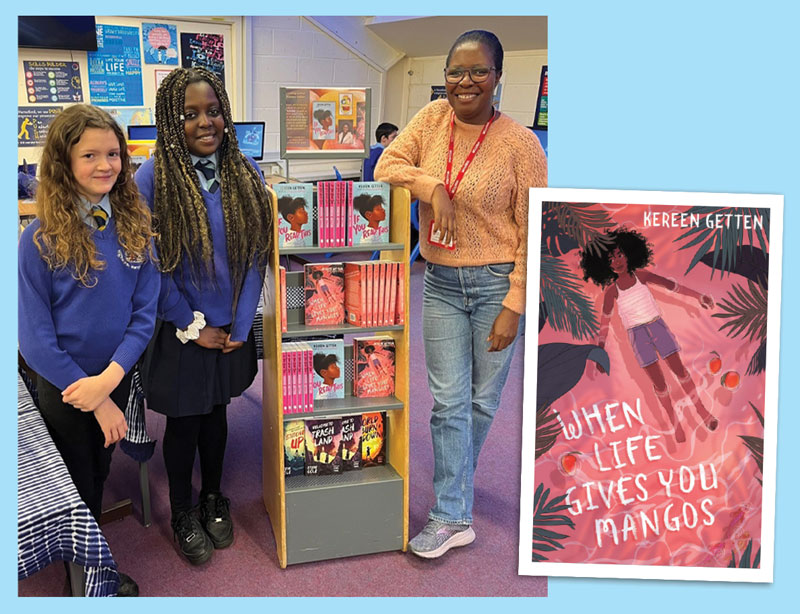

Kereen Getten with students at the Highworth Warneford School library in the UK, where she ran a writing class and signed books.Photo courtesy of Kereen Getten |

Author Kereen Getten conveys these ideas and others in her novel When Life Gives You Mangos (Delacorte, 2020). Like Keller, Getten remembers reading books as a kid and thinking, “That’s not how my friendships are. I just remember the turmoil of friendship, the heartache, the ‘Do they like me? What have I done? Am I okay? Am I fitting in?’” she says. “It consumes you. When it goes wrong, that becomes your entire world, and you almost feel like you’re falling apart, especially when you don’t know why.”

Getten notes, “Not every friendship has to be deep and meaningful.” There’s value to just being available for a game of “pick leaf.”

Though her protagonist, 12-year-old Clara, and another girl, Amber, “will never be close friends,” the relationship still has value. And when Clara feels attacked by her cousin (also her best friend), Clara’s anger drives her to exaggerate and make up offenses. Kids need to know it’s normal when that happens. Clara also assumes the worst of a new girl, who turns out to have exactly the unflappable, accepting temperament Clara needs; she becomes a close right-fit-for-right-now friend.

The power of apology; friendship tools

Fiction can also model the friendship-enhancing power of admitting fault and making amends. In Kwame Alexander’s Booked (HarperCollins, 2022), it’s this: “I guess what I’m trying to say, Coby, is I’m sorry.” John Cho’s Troublemaker narrator reflects: “I realize I’ve finally gotten it right. Not by cheating or by proving myself. But by saying…sorry when you’re sorry.” In Invisible, Jorge, who goes by George, says, “Listen, about what happened back there....It’s me. I’m sorry.” These stories don’t just normalize conflict; they communicate that redemption is possible.

A big mistake educators can make is assuming middle schoolers “are too old for really concrete social skills,” Fagell says: “I couldn’t even tell you how many times a child has come to me at lunch and said, ‘I don’t know how to ask someone to sit with me.’” She sometimes meets with pals who are at loggerheads. When Fagell says the friendship gets a vote—“What would the friendship say it needs?”—kids realize, “the friendship would say ‘Let it go. It’s not that important.’”

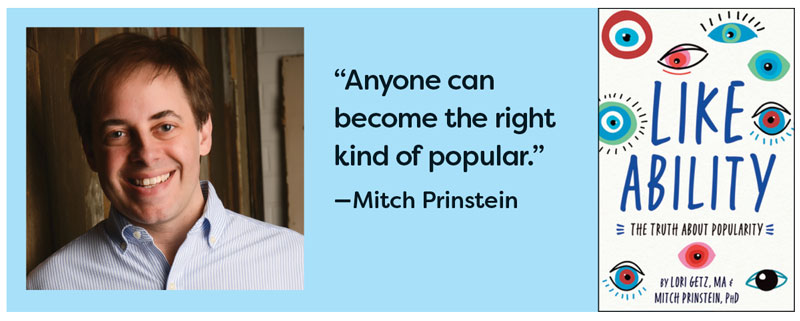

Nonfiction books for children, such as Like Ability: The Truth About Popularity by Lori Getz and Mitch Prinstein (Magination, 2022), can also provide kids with valuable tools to navigate friendships. Prinstein, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of North Carolina, studies popularity. Most middle schoolers don’t realize that there are two types of it: status and likability, he says. In the workbook-style Like Ability, for ages 12 and up, readers learn that “the most likable kids are the ones that make others feel happy, valued, and included,” and “anyone can become the right kind of popular.”

Growing Friendships: A Kids’ Guide to Making and Keeping Friends by Eileen Kennedy-Moore and Christine McLaughlin (Aladdin, 2017), is intended for ages six to nine, but its step-by-step coaching can help older kids, too: “It’s hard to move away from a familiar group, but it’s better to do that than to allow yourself to be treated badly again and again,” the book advises. In another chapter, kids learn, “Every friendship has an occasional Friendship Rough Spot” that’s not a reason to end it. The book also tells readers that friends who argue a lot may be better off separating, and that “Good friends make you feel like you matter to them.”

That’s the take-home message in Eggs as well: Everyone is just looking for someone to “wave back.” In When Life Gives You Mangos, Clara feels “the sting at the back of my throat” when her cousin “doesn’t care where I’ve been.” These stories subtly urge kids not only to invest in friends who turn toward them, but also, like the protagonist in Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, to know when a friendship breakup is the healthiest choice, Burns-Simpson says.

Burns-Simpson sees an additional role for nonfiction books: Coming to the library and noticing another kid poring over a book on a topic that gets you fired up is a route to deeper friendship, she says; especially, in her experience, for “many boys and boys of color.” Kids bond over fiction, too. That’s why Burns-Simpson connects, for example, manga readers; and it’s why she promotes “that open access hour, whether it’s before school begins or after, to allow kids to be able to just sit around and see what other folks are into.”

Fagell adds that children who identify as boys struggle with friendship instability and want “mutually satisfying, reciprocal friendships,” just as much as girls, but “social norms around things like stoicism and masculinity make it harder.” That’s where books like Troublemaker and Booked can make a difference.

And while friendships across gender often evaporate after age seven, there’s no good reason for it to be that way. So in When Life Gives You Mangos, Getten says she purposefully included boys in the story, though there was no romance. She describes Calvin’s friendship as “this gentle wave” around Clara.

“I really wanted children to see themselves,” Getten says. “I wanted them to see that friendship can be ugly, and it can be sad, and it can be miserable. But also, it can be just so beautiful. And it’s all okay.”

Gail Cornwall is a former teacher and recovering lawyer who now works as a mother and freelance writer in San Francisco.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!