America Was Great Even Before America: How Eldon Yellowhorn Is Reclaiming Indigenous History

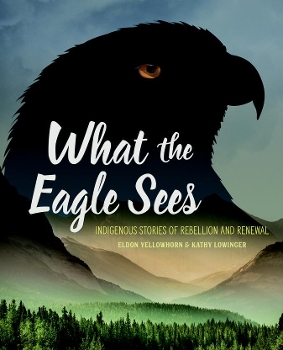

Dr. Eldon Yellowhorn and co-author Kathy Lowinger seek to reclaim Indigenous history in their book, What the Eagle Sees: Indigenous Stories of Rebellion and Renewal.

In this Op-Ed, Dr. Eldon Yellowhorn discusses the importance of Native American Heritage Month, preserving Native and Indigenous history free from the white gaze, and his research process for What the Eagle Sees: Stories of Rebellion and Renewal (Gr 6 Up, Annick).

What the Eagle Sees: Indigenous Stories of Rebellion and Renewal examines a history that receives little attention. My co-author and I documented the responses of Indigenous people after they encountered a glimpse of a larger world that arrived from beyond the ocean. The first contact with Vikings and their failed attempts to establish colonies was an event that produced no legacy beyond the features and artifacts left at sites such as L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada.

A few centuries later the arrival of Spanish, French, and English navigators created an entirely different aftermath. Once they returned home, they claimed they had discovered a new world inhabited only by “savage people.” These untruths inspired more fantasies of undiscovered lands populated by potential slaves.

For the last five centuries, Indigenous people have faced immense adversity because of those tales. Due to the Doctrine of Discovery (a papal bull issued in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI), they lost the right to occupy their homelands and consequently, the right to their autonomy. Indigenous people continue to live with the burdens and consequences of those encounters.

On Halloween, President Trump declared November as “National American History and Founders Month.” The President stated in his official proclamation, “Our Nation’s patriots and heroes have always been guided by the belief that America must shine brightly out into the world. Indeed, this conviction has been at the forefront of the American experiment since our founding.”

Although Trump also issued a proclamation on National Native American Heritage Month, he still decided to choose November as the debut of National American History and Founders Month. His timing, in addition to the intended purpose of this new holiday, was seen as suspiciously tone-deaf, if not ignorant and harmful, by Indigenous people and scholars. Since 1990, the month of November has been Native American Heritage Month.

Each chapter of What the Eagle Sees chronicles the death of Indigenous America. The text describes plagues and famine brought on by the chronic warfare that unfolded with the invasion of white European colonizers.

Dark topics such as slavery, dispossession, and genocide are discussed, but they are undeniable components of historical narratives that elevate and even deify heroes determined to explore an empty land inhabited by nameless people. The institution of white supremacy can explain the condition in which Indigenous people ceased to possess their homelands the moment a white man entered their country.

The book aims to attach identities to the people who resisted these incursions. Imperialists attempted to impose acts of assimilation on people who did not owe their existence to the kings and nations that engulfed them. However, the moments of brightness that broke the morose cycle of loss and death are also covered.

Our narrative arc must land on hope: it sets us apart from other approaches that emphasize a whitewashed American dream. Indigenous youth can read about ancestors who had the right mix of curiosity, imagination, and creativity to adapt to the impact of colonialism. They will learn the meaning of the heritage highway that memorializes the Trail of Tears.

Observing Native American History Month holds the potential to overcome negative stereotypes and misleading tropes that circulate in the absence of facts. For example, when white settlers first crossed the Appalachian Mountains and began occupying the Ohio River Valley, they came across many artificial earthworks constructed by Indigenous people. Despite the evidence of burials and grave goods with an autochthonous origin, the white settlers pushed propaganda about an ancient culture they called the Mound Builders.

At various times the Mound Builders were used as evidence that Phoenicians (a lost tribe of Israel) or the Vikings had settled in their environs. These artificial knolls even inspired William Cullen Bryant to compose The Prairies. Bryant’s poem gained popularity as citizens of the new republic justified their dispossession and deportation of the Cherokee Nation. It laid the foundation for an American mythos that normalized their maltreatment of all Indigenous people.

While we can now dismiss theories about the Mound Builders as uninformed speculation, there are still elements within archaeology that contest the premise that Native Americans were the first occupants of this continent. Despite the compelling evidence from studies of ancient DNA, a few archaeologists advocate the idea that the first Americans came from the Iberian Peninsula.

Although we take a global approach to our subject we also understand that history is personal. Each of us embodies the historical path our ancestors traveled in order for us to exist. Anecdotes and stories from my Piikani lineage were added to make the connections real and direct. The milestones my ancestors passed down through generations inspired the narratives and stories that form our oral histories.

I am especially interested in examining the mythology I learned about as a child and which I now study with an anthropological interest. The book features dramatic folklore with characters bearing names such as Scarface and Bloodclot because they enliven our imagination. However, I examined those same stories to ask how they informed the lives of my ancestors and to find the messages that they contain. When I recall those old stories, I feel like I am participating in a conversation that takes me across time.

I like referring to the early written reports from people who met my ancestors and related their impressions in their journals. For example, as a native speaker of the Blackfoot language, I knew our name for horse combined our words for elk and dog, but I never questioned its origin because I knew they were gifts from a supernatural being.

Horses were always part of my childhood and played a big role in our community; to imagine the world without them seemed farfetched. We depended on them for all our routines. We rode them to get from place to place. We harnessed them to pull our wagon in summer and our sleigh in winter. Yet I sometimes heard old people talk about the dog days before we got horses when the ancient Piikani made their tools from stone and turned clay into pots.

While conducting research for my master’s thesis, I came upon David Thompson’s Narrative. His prose, which chronicles his days in the fur trade, taught me how horses became known as elk-dogs. Suddenly I had the answer to a question I did not know to ask.

Although we shared our perspective of the past in this volume, we did not want to imply that there is no modern era for America’s first people. We wanted to show that nineteenth-century predictions of a vanishing race were misguided. Merely surviving into the twenty-first century is our victory.

We wanted readers to know that there are contemporary musicians, artists, scientists, writers, and ordinary people who see their ancestry in the soil of this continent. Therefore, emphasizing my voice was particularly important in telling this story.

Too often historians treated our side of the ledger as incidental to the history that really mattered. We were regarded as broken, conquered people who contributed nothing substantial to the historical record, or to modern times.

Observing Native American History Month brings history to the forefront of popular culture. It is the one time of the year when average citizens look to the origins of Thanksgiving and see Native Americans as essential to the narratives about the founding of the country.

November is a time to contemplate the false impression left by writers who overlooked our presence and forgot our contributions to modern America.

We must reclaim it so that Indigenous people can use our moment to show that we are still here and using our talents to make our world brighter, just as we have always done.

|

| Photo by Annick Press |

Dr. Eldon Yellowhorn (Piikani Nation) is an award-winning author and professor of Indigenous Studies at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. He employs archaeological methods to study the history of his community in Alberta, Canada. His research includes Blackfoot language revitalization using AI and machine learning techniques.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!