Access Denied: Florida Teachers Discuss Life and Lessons in Classrooms Without Books on the Shelves

Some Florida districts have ordered their teachers to remove titles until they are deemed appropriate. In others, teachers are acting proactively to avoid consequences. But how do you teach with empty shelves? Three teachers share their stories.

|

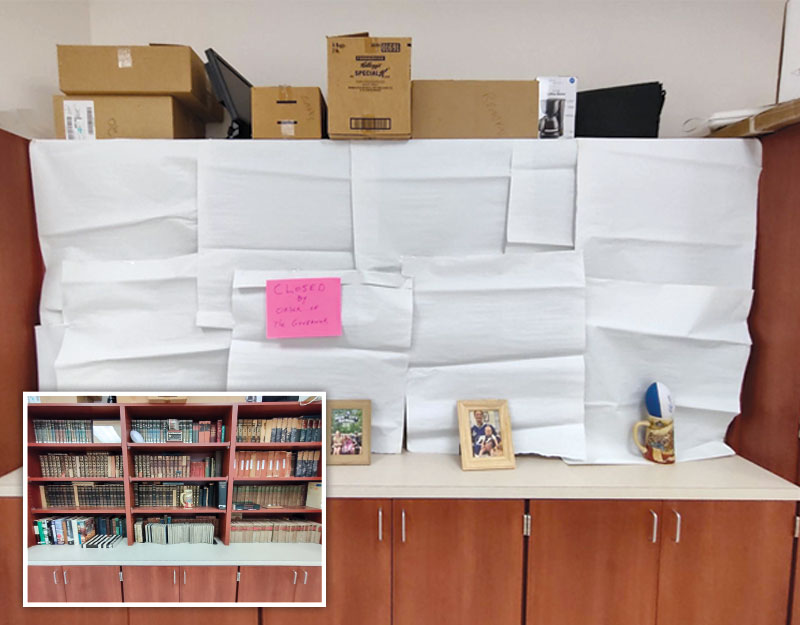

Don Falls’s classroom library before and after the order to hide the books.Photos courtesy of Don FallsDominguez |

Related articlesTeacher Fired for Tweets About Book Removals Continues Fight Against Censorship |

The pictures and videos were startling. Empty shelves, books hidden by construction paper, bookcases turned to face the wall to eliminate access to titles.

In Florida, two recent laws—one requiring all books in schools to be vetted by a media specialist before being made available to students and another leaving teachers vulnerable to felony charges for distributing “harmful materials” to minors—have created a dearth of books in schools across the state.

In at least two school districts, teachers were required to hide their classroom libraries until the books could be vetted—a process that could take months. In areas where those orders have yet to be issued, teachers are removing books anyway, censoring classroom shelves proactively to avoid punishment.

SLJ spoke to several teachers about the impact of the empty shelves on students and teaching.

Don Falls

Manatee High School, Bradenton, FL

Earlier this school year, a student approached government and economics teacher Don Falls in search of some presidential biographies. Falls happily obliged the request. Today, however, the student’s request would be denied. All of Falls’s presidential biographies are now off-limits.

Falls has taught for 38 years—and collected books for his personal and classroom libraries for 50 years. He estimates that there are between 450 and 500 books in his classroom at Manatee High School in Bradenton, FL, and another 1,500 at home. He sometimes rotates books between his home and classroom depending on his students’ interests and what he’s teaching his senior government and economics classes.

Then his district instructed teachers to hide all of their books until they were vetted and approved. Initially, Falls covered the books with construction paper and a note that read, “Closed by order of the governor.” Soon after the original instruction, the district said their books could be visible, as long as students didn’t read them.

A month after the order to bar access, Falls’s collection available to students shrank to 12 titles. The approved books included the first two volumes of “Great Issues in American History”; The Worldly Philosophers; Freakonomics; and a collection of Charles Dickens’s works with Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, and A Tale of Two Cities.

“I have my dozen approved books sitting by themselves over on a bookshelf,” says Falls. “That image is a little bit comical.”

The rest of his books are being slowly added to a database and vetted.

On the no-touch shelves are books including a 36-volume set of works by Voltaire, presidential papers from every president, and works by Hemingway, Cervantes, Plato, Aristotle, and Freud. His vast collection of off-limits American history titles includes some that are a few hundred years old, he says.

Falls, a Manatee High School graduate himself, was shocked to see things escalate to restricting access to books. In recent years, he’s noticed students read for pleasure less and less, and one of the reasons he keeps a classroom library is to try to show the importance of reading. For him, the loss goes far beyond the classroom.

“I am an avid reader and have been my whole life,” Falls says. “I also believe in exposing students to books. Reading is fundamental to not only a successful education, but I think to a successful life—being able to read and take that information and make it part of you.”

|

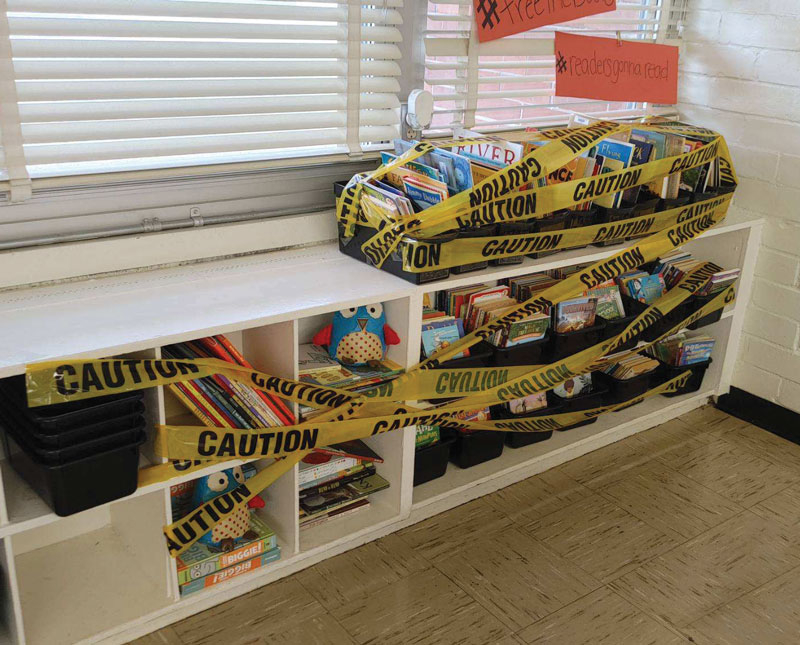

Andrea Phillips’s inaccessible titlesCourtesy of Andrea Phillips |

Andrea Phillips

Duval County Public Schools

At the end of each class, reading interventionist Andrea Phillips would let students who finished their work get a book from her classroom library and read for pleasure. She also had a Little Free Library from which kids could take books to take home.

“That has all stopped,” says Phillips.

Earlier this year, Phillips sat with colleagues and watched a video outlining the district’s new rules about books in the classroom.

Paula Renfro, the district’s chief academic officer, instructed teachers that all books in classroom libraries were to be “covered or stored and paused for student use” until they had been reviewed and approved.

After the meeting, Phillips returned to her classroom and made a tearful video saying she was about to box up all her books, 200 to 300 titles.

Phillips has had to find other activities to occupy those who finish the day’s lesson before class ends. She spent a day putting together literacy activities and introduced them to the students so they could do that when their work is finished.

“It’s not the same,” says Phillips. “They’re working on more literacy skills now, which is good, but I would prefer to see them spending those five minutes enjoying a book and learning to build that love of reading. That’s my job.”

She has found a few approved guided reading books (meant to accompany curriculum) to substitute for the missing titles, but her students haven’t shown much interest.

“When’s the last time you picked up a book for pleasure to read about Abraham Lincoln?” she says. “So my third graders are not doing that either.”

They much prefer the popular “Dog Man” series that is waiting to be vetted, she says.

Someone in her school suggested she use the time to give students a passage and reading comprehension questions.

“That’s great, but it’s kind of like you getting off work and finishing your job and your boss saying, ‘Here’s another report for you to do. Have fun with that. Here’s your reward for downtime.’ ”

The restriction of access was supposed to be temporary, but about a month in, Phillips’s classroom library remained covered. She says her kids, mostly third graders, ask when the books are coming back, but she can’t give them an answer.

“I spent a lot of my personal time curating that collection for my students, and it brings a lot of joy to my heart to have my kids come in and say, ‘Oh, you got new books?’ ” Phillips says. “To see them actually excited about picking up a book and taking it home…it was pretty heartbreaking to lock all of those things in my cabinet.”

|

Books in Aurora Dominguez’s closet.Courtesy of Aurora Dominguez |

Aurora Dominguez

South Florida

Aurora Dominguez’s school district recently began requiring teachers to get approval for any books they plan to use in the class curriculum. The district has not asked educators to remove their books, but Dominguez put hers away as a precaution.

“I put my books in my closet to have them out of sight as I seek approvals as needed,” says Dominguez, who teaches high school English, journalism, and research writing. “I am just being careful because I like my job, and I am waiting to see what happens next... I’m trying to protect myself. It might sound extreme, but I honestly do not like the direction where a lot of things are going.”

Titles like Furia by Yamile Saied Méndez, about a teenage Argentine soccer player, and Lobizona by Romina Garber, about an undocumented immigrant in Miami, are now stacked hidden from view. Dominguez taught Furia in the past and hopes to include Lobizona in her curriculum in the future. For now, though, the books are inaccessible to students for lessons or borrowing to read on their own. Books like these were especially hard for Dominguez to put away. She and many of her students are Latin American and could relate to these stories, she says.

Since the new rules, she has submitted one book to teach— Sense and Second Degree Murder by Tirzah Price—and received approval.

Dominguez, who was her school’s 2021–22 Teacher of the Year, began her career as a reporter and editor, but after many years she says she felt the call to become a high school teacher. She still reviews books and encourages her students to become readers.

Former students are shocked to see the empty shelves now when they visit Dominguez. One of the things they remembered most about being in her classes was the teacher lending her books to students.

Dominguez is unsure what the future holds. The pandemic and now the new rules and laws regarding books and access have all taken a toll on her mental health—and her students’, she says. She wants to stay in the classroom, so she is placing a priority on her mental health and life outside of school.

“My advice to teachers is to realize that caring for themselves matters,” she says.

Colleen Connolly is a Minneapolis-based journalist who writes about children and education, and more. She can be found at colleenmaryconnolly.com.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!