School Libraries Are Vital to Black and Latinx Students

Libraries can provide safe spaces from bullying and overpolicing.

“These kids won’t go to the library. They don’t read,” a teacher said on my first day as a public school librarian. I worried that she was right. But within a few weeks, I had the opposite problem.

The school was located in a small urban township in New Jersey. Each morning, kids were sitting outside the library media center door, waiting for me. The principal asked me to open the library before classes began and after they ended. About 120 students visited the library during each of the three daily lunch periods.

After school I was usually exhausted, surrounded by about 100 students, mostly athletes. I was supposed to close by 4 p.m. but sometimes would stay later. Football players would fool around, hiding under the tables, holding on to the legs when I announced it was time to go home. I asked one of my regulars why she and her friends never wanted to leave. “What do you do when you’re not here?” I said. “Nothing,” she replied.

I got a fuller picture of their lives one afternoon in December 2013, after a snowstorm, when I was making the 10-block walk from school to the train station alongside groups of students. I was hurrying to make the next train—and to avoid getting caught in a snowball fight. I noticed a few police officers talking to students in the street, but figured they were there just to discourage kids from throwing snowballs at passing cars.

A male officer shouted at a group of about four middle school boys. I had my earbuds in, so I couldn’t hear his command. The boys had headphones on, too, and kept walking.

Then the officer pulled out his gun and pointed it at them. I took out my headphones. He shouted at them to stop walking. One or two glanced at him, but something didn’t register. They kept walking. He moved closer, hands shaking as he pointed the gun at each of the students, ordering them to get down, facedown, in the snow.

The boys held up their hands, frightened, and lay on their stomachs. The officer then ordered me and the kids near me to stop. He aimed his gun at different points in the crowd, so each of us could feel as if we were in his crosshairs. My legs shook. I had never had a gun aimed at me and hadn’t trembled like that since I was a little girl, if ever. More police officers and cop cars appeared so fast, it felt as if they had teleported there. Between six and 10 officers took positions with their weapons.

This was before Walter Scott, before Eric Garner, Philando Castile, before videos of black men being profiled and murdered at the hands of police began going viral. I didn’t have the instinct to take out a phone and record. No one did.

The cops told the boys—just the boys—to line up. They motioned for each boy to lean against a chain-link fence, while ordering the girls to remain in place, frozen. The boys were patted down and released, one by one.

I tried to ask why they were doing this. The officer who started it all pointed his gun directly at my chest, annoyed, motioning for me to go.

Some of the high school kids around me had picked up younger siblings from the elementary school and were bringing them home. One girl later told the principal that she was holding the hand of her five-year-old sister.

After that, I was more conscious of how stress and trauma impact students’ decisions, because I was aware of my own lingering trauma. I couldn’t get the incident out of my mind. I had nightmares and was increasingly frustrated that though the incident was reported to the district superintendent by the principal, there was no further response from the superintendent, police department, or city officials.

At that time, I also worked part-time as an evening reference librarian in a predominantly white town. I spoke with parents all the time and knew the uproar it would have caused if police had pointed guns at their children without explanation or apology.

My students received messages every day that their lives were less valuable, that they deserved to be treated with callousness and disrespect. I understood why they lingered after school. The public library in town was closed for most of that year, making my library one of the only free places where they could sit together and be with friends.

|

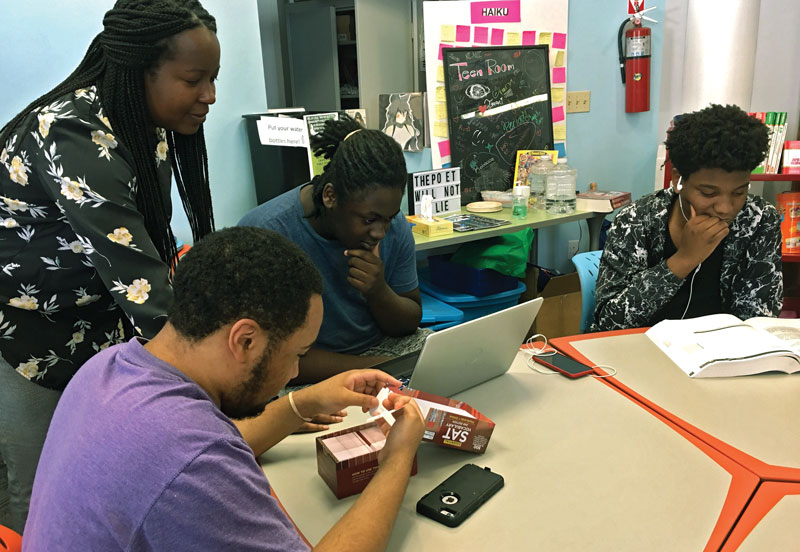

Maisy Card (left) with young patrons at the Newark (NJ) Public LibraryPhoto courtesy of Noelle Williams |

Safe spaces

In her article “The School Library as a Safe Space,” teacher librarian and 2016 SLJ School Librarian of the Year finalist Anita Cellucci writes that the way “to create a safe space for students is to make them part of the process so that they not only have ownership and autonomy, but also feel part of a community.” Black and Latinx teens are frequently sent messages that they are not welcome in many spaces within their own communities. They are frequently met with a barrage of “No Loitering” signs in their own apartment buildings and streets.

While teens in general are often discouraged from loitering, it is no accident that the law disproportionately affects black teens. Loitering laws were first enacted and enforced specifically to police the actions of African Americans during the Jim Crow era. In New Jersey, according to the ACLU, black people are between three and 10 times more likely to be arrested for loitering.

While it is important to highlight the academic support that libraries provide, we must also emphasize that libraries are safe spaces for many who face physical danger when they socialize in groups in public, including black and Latinx teens, often subjected to overpolicing in their communities.

One of the most famous cases that highlights this tragic reality is depicted in When They See Us, Ava DuVernay’s miniseries about the Central Park Five. More recently in New Jersey, an investigation found that in July 2016, after an Independence Day fireworks display, a group of black teens leaving a Maplewood park, described by police as an “agitated crowd,” were forced to march over the town border into Irvington. The teens who resisted because they lived in Maplewood—not in Irvington—and wanted to go home, were pepper sprayed and kicked by officers before being arrested.

|

Photo by Getty Images/Fstop123 |

Fighting the ‘Geography of No’

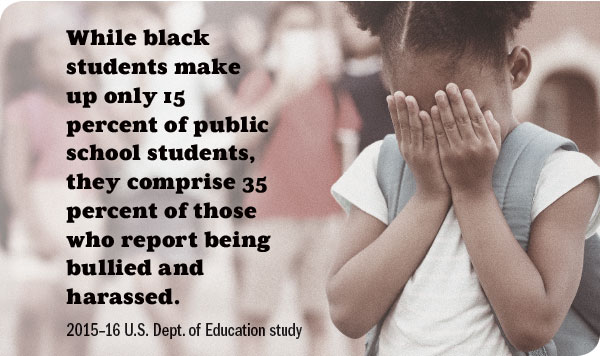

Black and Latinx youth are often overpoliced inside the school, too. While black students make up 15 percent of the U.S. public school population, they are the most severely punished. In 2016, they accounted for 31 percent of in-school arrests and law enforcement referrals. Also, while black students make up only 15 percent of public school students, they comprise 35 percent of those who report being bullied and harassed, according to a 2015–16 study by the U.S. Department of Education.

The good news is that more libraries are creating teen spaces that counteract the negative messages teens receive in public spaces. The first designated teen space to open in the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL) in 1994 was a response to the vilification black and Latinx teens faced after the Los Angeles riots.

Anthony Bernier, LAPL young adult librarian at the time, was “appalled at the way the media was blaming young people, and [he] started to think about the role the library had in dealing with young people in a real way, as opposed to institutional responses.” In Bernier’s article, “A Library ‘TeenS’cape’ Against the New Callousness,” originally published in Voice of Youth Advocates (VOYA) in 2000, he describes how library teen spaces can deliberately counteract the zero-tolerance public policies inflicted on urban teens through what he calls the “Geography of No.”

In conversation, administrators at my school always discussed the library as purely an academic space. Since it served a low-income community, they wanted to make sure students had all of the resources to get their work done. Some of those administrators would walk into the library and admonish the students for putting their heads down, having bottles of soda out on the table, or looking at their phones instead of reading or doing school work.

I found rules encouraged by the administration—no eating, no sleeping, no cell phones—difficult to enforce, and unnecessary. Sometimes, the most valuable support a school library can offer a student is a place to put their head down when they are feeling overwhelmed or exhausted—for reasons that might include being policed outside of school, overly disciplined within school, or bullied.

I began to think less about enforcing rules but rather of ways to make the library a place of refuge and as Cellucci describes, a place of “solace and protection” and positive community interaction. My school cafeteria and hallways were too chaotic for some students, including those who stayed clear of both because they were bullied. One day when the library was closed for testing, I saw a boy who was a regular during lunch walk circles through the hallway for the entire 30-minute lunch period rather than go to the cafeteria.

I eventually abandoned the no eating rule.

A few years after leaving that school, I began working at the Newark (NJ) Public Library as a teen services librarian and helped design the first teen room alongside Heidi Cramer, former assistant director of public services. I initially worried that teens wouldn’t come. But as with the school library, when black and Latinx teens realized that they had a safe space for themselves, where they could socialize, they showed up. We see an average of 350 young people a week during the school year.

“When school is out for the summer, we have teens who stay at the public library from the time we open until the time we close,” says Karl Schwartz, a teen librarian who runs the teen space at the Hoboken (NJ) Public Library. “For black and Latinx teens who come from communities that are overpoliced and underresourced, having a space that is set aside for them, that they can have a sense of ownership over, is crucial.”

A moral defense of libraries

Since 2000, American public schools have lost 19 percent of their school librarians, according to SLJ research. Most frequently, those losses have been in districts that serve black and Latinx students. “Districts which have not lost a librarian since 2005 are 75 percent white, while the 20 districts that have lost the most librarians had on average 78 percent minority student populations,” according to Edweek.

Being an urban school or public librarian means always needing to justify the value of your work. Often we make the argument for why schools need libraries solely through the lens of academic achievement. We collect data, make charts and graphs, and track the minutiae of student progress to prove the immense value of a library. But all of this number crunching does not tell the whole story.

In order to paint a fuller picture of what a school library can do for a community, we also need to make a moral argument, one that encompasses the social context in which black and Latinx teens live in the United States and takes into account the structural barriers they face in their daily lives.

This argument might not be easily captured in data. But it may be the most morally persuasive case we can make for the continued existence of school libraries and dedicated teen spaces in public libraries.

Maisy Card is a writer and a teen services librarian at the Newark (NJ) Public Library.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Library Teacher

Articles like this can be divisive. I work in an area where my students are low-income and not minorities. The library is a special place for them too.Posted : Aug 13, 2019 11:22