School Librarians Share Concerns, Hopes In the New School Year

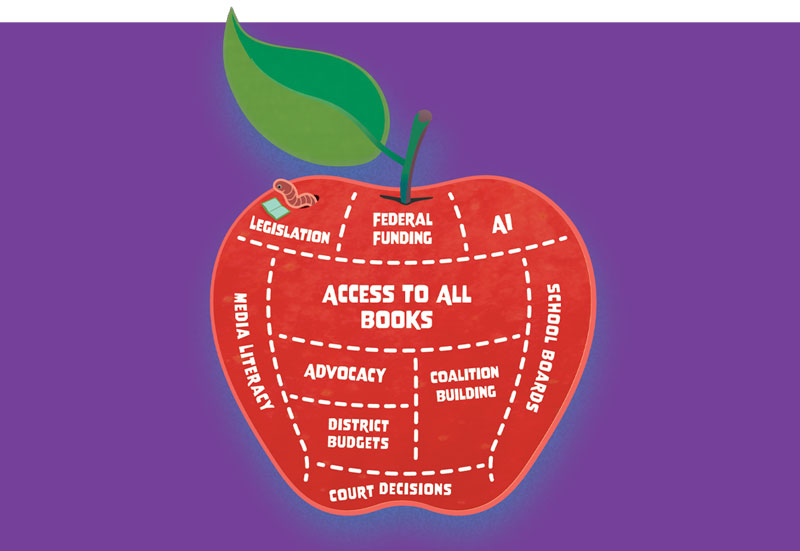

Censorship, AI, and federal funding top the list of concerns for school librarians heading into the 2025-26 school year.

|

Illustration by Mark Tuchman for SLJ |

At a Title I district in New Jersey, a high school librarian was already concerned about her students heading into the 2025–26 school year. The loss of Institute of Museum and Library Services funding meant limited or possibly no databases for research. Frozen federal funding threatened after school programs that keep kids safe, fed, and on-track academically. Then, on July 14, the Supreme Court issued a shadowdocket ruling with no explanation that allows the Trump administration to proceed with its dismantling of the Department of Education. And the librarian’s worries escalated.

Students can’t thrive without the needed resources, and she can’t provide them in her district without federal support, she says. The loss of the Department of Education’s funding could also result in job losses for educators in Title I districts. It will especially hurt English Language Learners, students with special needs, and those who required the department’s Office for Civil Rights to ensure equitable treatment and access to an education, she says. In addition to the day-to-day academic and library concerns, she has seen the impact of undocumented students carrying daily fear of detention and deportation of them and their families.

“I don’t believe it’s possible for my kids to feel safe in the environment they are in today,” she says, noting that the students are participating less in activities outside of school and worried their parents might not be there when they get home. “If you don’t feel safe, you can’t learn.”

The librarian is not just worried about the impact of government actions on the students this school year, she is worried about aborted futures.

“My kids all want to go on to college and to graduate school, and my kids are brilliant students,” she says. “With the Big Beautiful Bill, it’s now going to be harder for them to get the funding. My kids all need federal funding and grants [to go to college].”

In Oklahoma, Amanda Kordeliski shares the concerns.

“I’m very concerned with the [Supreme Court] decision and disappointed in the ruling, but we’re going to keep going forward,” says Kordeliski, noting the direct impact of loss of grants and funding on librarians’ work and the larger, long-term ramifications, especially in states that don’t properly fund education and rural areas where it’s more difficult and expensive to access resources.

[READ: In “Devastating” Decision, Supreme Court Rules In Favor of Parents in Mahmoud v. Taylor]

“I don’t know that we can even really explain the long-lasting impact with those kids, because if they don’t have access to any resources, they’re not developing the job skills that they need,” she says.

Kordeliski must find a way to meet the needs of her students, but as the new president of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), she must also help AASL’s members who head into this school year with new and more complicated concerns and fewer resources.

“Every state operates differently,” Kordeliski says. “We are trying to reach out and make sure they have the resources to support their needs. Being able to assist our members, no matter which state they live in, is really the goal. We have tried to be more proactive in reaching out to make sure that we know what the gaps are [and] try to brainstorm how to bridge those gaps with the resources that we have.”

Thoughts on the new year

SLJasked school librarians what was on their minds as they embarked on the 2025–26 school year. In a sign of the times, only a couple of respondents (in interviews and in written response to the online query) permitted their names and schools to be used. Anonymity was requested for fear of angering their administration or becoming targets of their communities or online antagonists outside of their area.

While every school has its own unique issues, there were common threads in the responses. School librarians are grappling not only with the stress of local budget issues but also with the uncertainty of federal funds—those already allocated by Congress for 2025, which have been frozen by the Trump administration, as well as those in the federal budget for 2026. The IMLS cuts leave public library partners unable to step in and fill the gap.

Censorship, restricted access to books, and soft censorship remain a concern for many, bringing added work hours, stress, and the responsibility of defending selections. In addition, public pressure and personal attacks have increased in number and vitriol over the last five years.

In Texas, a new law that goes into effect Sept. 1 gives school boards, not librarians, approval over library book purchases and removals. The bill also allows for the creation of an advisory committee to oversee these collection decisions if there is a petition from either 50 parents or 10 percent of a district’s parents.

Nationally, the June Supreme Court ruling inMahmoud v. Taylor could alter book selections for everyone, impacting the number of titles with LGBTQIA+ representation and requiring planning for parental opt-outs on any read-aloud, discussion, or assignment.

“It’s a nightmare,” says a library coordinator at a charter school in rural Michigan. “I’m thinking about how it’s going to apply in our elementary and middle schools and the units they do, and the parents that could take issue with books that their kids are bringing home. It’s a lot.”

When she spoke toSLJjust days after the decision was announced, she was trying to create a plan for librarians to support teachers “and provide a united front to make sure our kids are still reading what they should.”

She is lucky to be somewhat insulated at a charter school with a lot of supportive parents, she says, but it is still a battle against the loud voices of those who do not support the library’s efforts. “Going into this year, we’re going to have to make sure our policies are up-to-date and find the support from our admin to make sure it doesn’t affect our students,” she says. “It will be better to be proactive. It’s better to have those policies in place and have the harder conversations before [something] happens.”

Librarians also expressed concerns about issues beyond funding and books, such as the use of AI.

“[Our] current administration doesn’t see the value of library instruction in the [middle school]; they believe classroom teachers can do it all,” wrote a librarian from New York City who listed her biggest concern as the use of AI by students and the administration’s support of it. “Beyond wanting kids to use AI ‘effectively,’ administration has been allowing/telling kids to use Chat GPT to review written work to ‘make suggestions’ to better the writing. In the past, middle schoolers have been expected to peer edit—a skill I think is much more valuable to the 13-year-old brain.”

Focus on the students

Despite the myriad issues and obstacles, those who responded to us always returned to the same goal—meeting the needs of all of their students.

“I always look forward to the new school year with a mixture of excitement and trepidation,” Jennifer Cooper, librarian at Osbourn High School in Manassas, VA, responded. “The excitement comes from knowing that I’m going to make connections with students and staff throughout the year. I also look forward to helping students find that right book for them.

“The trepidation comes from not knowing how often we’re going to have to close for state-mandated testing. In recent years, the number of tests and how often they are given have increased. My goals are always about providing a place for students and staff to relax, find a good book, or enjoy a game of UNO or chess with their peers.”

The interruption from standardized testing is just one of librarians’ obstacles, which include the perpetual struggle to get school administrations to understand the role and impact of a full-time library media specialist and quality library programming.

“My hope for the ’25–’26 school year is to be able to show the value of school libraries to my staff and stakeholders,” Missouri high school teacher-librarian Jamie A. Becker wrote. “We have just opened a beautiful new school, and my library is double the space it was. It has everything I could hope [for]. But I fear it will still be utilized as a traditional space instead of a dynamic, flexible space for gathering, collaboration, and learning. I want there to be a ‘learning commons’ feel and move beyond the traditional uses. My goal is to show [a library’s] value outside of just being a quiet place to send students.”

Another ongoing issue for school librarians is being saddled with more responsibilities while facing budget cuts impacting library programs. A library media specialist in Minnesota must teach classes across two buildings and manage all of the administrative responsibilities, checkouts, and shelving for both libraries after losing the paraprofessional who assisted in the past. The school has also added another grade to the building, requiring more middle school titles for the collection.

“I’m feeling completely overwhelmed,” that library media specialist wrote. “I had so many ideas and plans for this next school year, but now I feel like I’m barely going to survive.”

In addition, the district is looking at a large budget cut for 2026–27, with the fear of losing library programs completely looming over this year.

Concerns about library job security have been around for decades. This year is no different. In Spokane, WA, secondary school librarians report being moved into the classroom, according to one middle school librarian who is spending her summer studying the curriculum for a subject she has never taught before. The school libraries will be opened for a limited number of periods, she says. Students will lose research and media literacy instruction, and there won’t be time for librarians to collaborate with teachers in the classroom.

In Chicago, librarians are celebrating a new Collective Bargaining Agreement under which Chicago Public Schools will add 30 school librarians in each of the next three years. It is a big win for school librarians in the country’s third-largest public school district, but the plan for implementation and the needed funding are a work in progress. It is unclear how the district will bring in the 30 new librarians this year.

[READ: The Cost of Losing IMLS Funding]

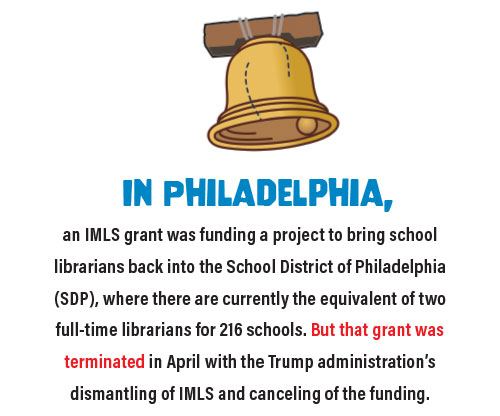

In Philadelphia, an IMLS grant was funding a project to bring school librarians back into the School District of Philadelphia (SDP), where there are currently the equivalent of two full-time librarians for 216 schools. But that grant was terminated in April with the dismantling of IMLS. The status of such IMLS grants is moving through the courts, including a lawsuit filed by the American Library Association (ALA v. Sonderling). A separate lawsuit filed by 21 state Attorneys General (Rhode Island v. Trump) resulted in a preliminary injunction that returned grants to only those 21 states, but Pennsylvania was not part of the lawsuit.

“On a positive note, SDP has announced that the district is committed to the goals of the grant, to see that all their district-operated schools eventually have school librarians and libraries,” says Deb Kachel, a member of the core planning board of the Philadelphia Alliance to Restore School Librarians, which is managing the project. “We are continuing to work on the grant objectives—developing educational pathways to build a cadre of certified school librarians and to develop a five-year strategic plan that aligns with district goals. However, funds to pay for this ongoing grant work have not been determined.”

A reason for hope

A reason for hope

Through it all, librarians are showing up every day with one clear focus. When asked what she was looking forward to, the Michigan librarian responded without hesitation: “Our students,” before excitedly discussing “bulking up” the high school library collection, particularly with a larger graphic novel selection, and creating a student advisory board.

Working for the students keeps these professionals motivated, and while many are feeling the effects of the difficult fight for the resources and ability to support all kids and a comprehensive public education curriculum, at least one person interviewed found reason for hope.

“For the first time, I’m seeing people who make decisions for education asking questions about school libraries, rather than just listening to some very loud and often misinformed voices,” says a school librarian from Oklahoma. “Those questions give me hope. People are looking for reality. They are looking for truth beyond extreme talking points. And I’m excited about that.”

She is focusing on creating new relationships with the education decision-makers in her state and offers this advice to others around the country looking to create important connections: Start within your own school community, making sure fellow educators in the building understand what librarians do for students and staff. Then move outside the school to the district and school board level, families, stakeholders in the communities, and local and state elected officials. “Most decisions that affect us are made at those levels,” she says.

She hopes that what she sees in her state is a sign of a turning tide and could provide hope and a road map for embattled areas across the country.

“We in Oklahoma have lived with what the rest of the nation is seeing right now, with a very conservative majority,” she says. “We understand how to build relationships and get beyond certain rhetoric and show how we all are reaching [toward] the same goal, which is helping our learners find success.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!