Planting the Seed for Brian Selznick's 'Big Tree' | SLJ 2023 Stars

Brian Selznick’s new book originated as a movie with Steven Spielberg six years ago. When production stalled during the pandemic, Selznick created a 528-page illustrated novel instead.

|

All artwork by Brian Selznick © 2023 Universal Studios |

It’s not every day a writer’s agent calls and says Steven Spielberg would like to work with you. But that’s what happened to Caldecott Medal winner Brian Selznick in 2017.

After getting over his initial shock, Selznick signed a nondisclosure agreement and talked to an associate of the famed director.

“So I got this call,” Selznick recalls, “telling me that Spielberg wanted to make a movie about nature from nature’s point of view, and he wanted it to be set during the Devonian era before the dinosaurs, when the world was mostly covered with plants. And they wanted me to write it.”

There was one big problem. The author and illustrator of The Invention of Hugo Cabret doubted he could pull it off.

|

Photo by Brittany Cruz-Fejeran |

“I don’t write about nature,” says Selznick. “It’s not really anything I’ve done before. I wrote one screenplay based on my book Wonderstruck for Todd Haynes, but I’ve never written an original screenplay. But I learned a long time ago that sometimes, you just have to say yes, throw yourself into the deep end, and see what happens.”

Before long, Selznick found himself on an airplane to California for an in-person meeting with Spielberg and Chris Meledandri, the founder and CEO of Illumination, a computer animation studio. Meledandri is also the producer of several films, including Ice Age, Minions, and Sing.

Selznick was eager to attend the meeting but kept his expectations low.

“I assumed that at the end of the meeting, we would all realize that this isn’t a movie that I could do,” he says. “But I hoped that we would hit it off. So that maybe if there was a movie we could do in the future, we would know each other, which seemed very exciting.”

That chat about a movie started a process that ultimately led to the novel Big Tree, published by Scholastic in April of this year. That result came after a couple more meetings about the movie, a lot of research, and the disruption of the global pandemic.

The initial meeting went so well that they planned to meet again in a month, and Selznick was tasked to do some research in the interim.

The initial meeting went so well that they planned to meet again in a month, and Selznick was tasked to do some research in the interim.

When he returned home to New York City, one of the first things he did was meet with Jamie Boyer, a paleobotanist at the New York Botanical Garden. Boyer is the garden’s president of education and vice president of children’s education. He has a master’s degree in botany/paleobotany and a PhD in botany/plant biology and has conducted a lot of research about the Devonian era.

“He’s the one who really started explaining to me how during the Devonian era, there were very few insects, which meant there was very little biodiversity, and that’s why the world was mostly covered with ferns,” says Selznick. “And I just didn’t think anybody would want to watch a movie about ferns.”

Boyer’s description of the time period helped Selznick decide to move the setting for the screenplay forward more than 300 million years to the Cretaceous era, which is toward the end of the dinosaur age.

“If we took a time machine back to the end of the dinosaur age, somebody who knows about plants would see a lot of plants that they know,” says Boyer. “A plant person would probably be able to identify a sycamore and a magnolia and a palm tree, and then here comes a T. rex, so it’d be a weird world to be in as a whole.”

By the time Selznick met with Spielberg and Meledandri a month later, he had completed 200 small drawings about how the movie could open. He copied the drawings and put them into a little book, which he gave them in gold boxes held together with yellow rubber bands. Selznick walked them through each drawing and shared his vision for the movie.

His work impressed them, and they sent over a contract for him to write the screenplay. Over the next two years, he worked on the project, meeting with Spielberg and Meledandri two or three more times to develop the story.

“I realized by basing everything in science, I could try to tell a story that is informing the viewer about the real ways in which nature works,” says Selznick.

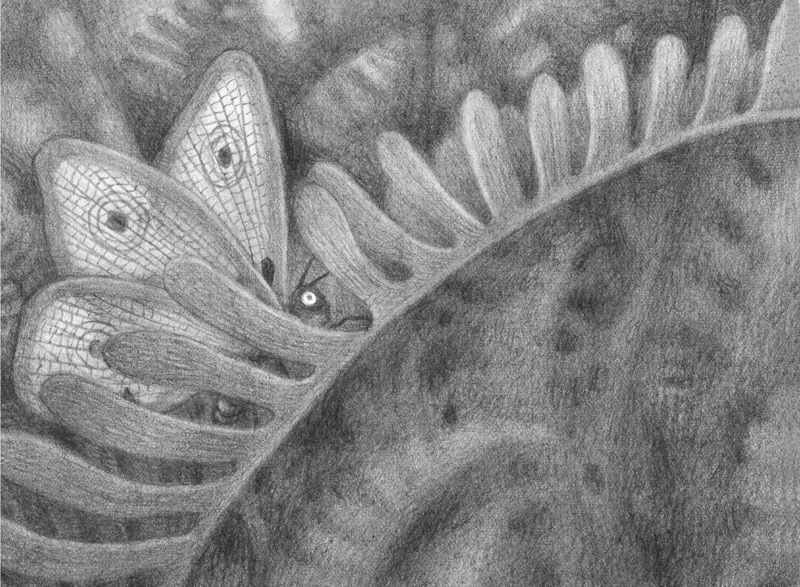

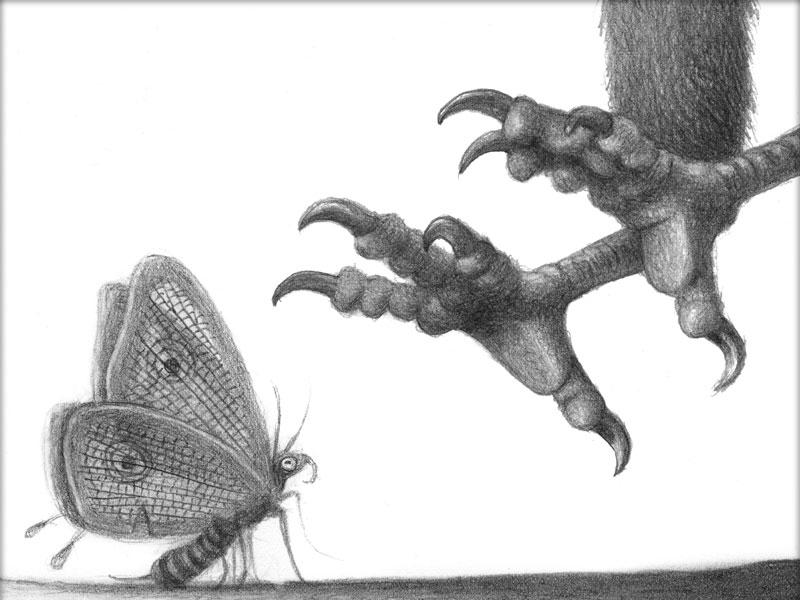

The story would be centered on two sycamore seeds, Merwin and Louise, who are siblings on an epic adventure in which they have to contend with several traumatic events, including a massive fire, a volcanic eruption, and close encounters with dinosaurs. Their journey begins with their search for fertile ground and ends with them trying to save the world.

“I decided to make the main character seeds because I wanted them to be able to move around, and trees have roots,” says Selznick. “And so because I normally write about children who have been separated from their parents, I realized that seeds themselves would be a good metaphor for kids who leave home and have to go find a safe place to grow.”

|

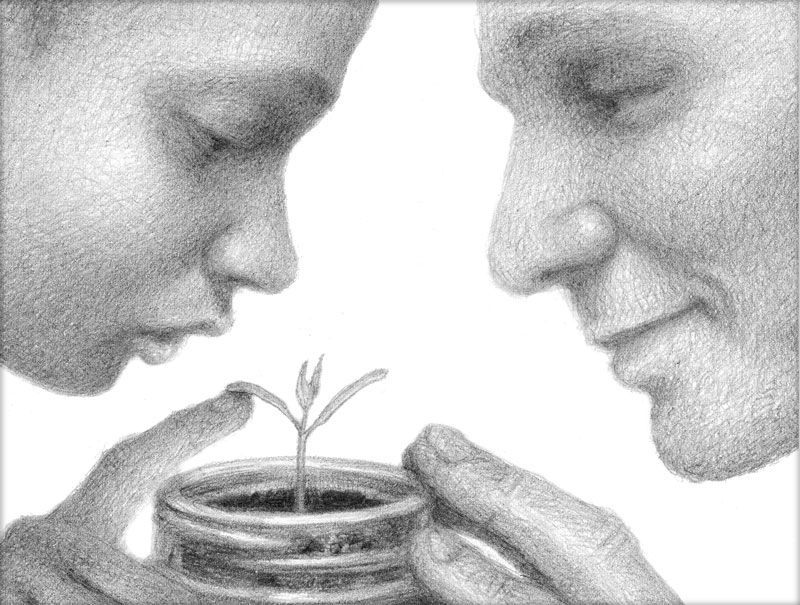

Selznick rendered each highly detailed illustration with a pencil under a magnifying glass. |

Pandemic pivot

Things were coming together nicely, and then the pandemic hit in 2020, grinding everything to a halt. “It became very clear for various reasons that the movie was never going to happen,” says Selznick.

But he wasn’t ready to give up on the project. He asked Spielberg and Meledandri for permission to turn the screenplay into a book, and they approved.

“By this point, I had really fallen in love with the story and the characters,” says Selznick. “Even though it never was actually supposed to happen, I feel like the book is the form that this story was always supposed to be in.”

Selznick wasn’t supposed to do any of the pictures for the movie. That job was going to animators. The team was in the middle of figuring out where the eyes and mouths would go on the seeds, and that problem went away when the screenplay became a book.

“For the book, I realized that the idea that the story has to be based in science should be extended to the images as well,” he says. “So the seeds are just seeds, and they have no faces. But Sycamore seeds have little bits of fluff on the end that help them move through the air. So I gently anthropomorphize them to make them act a little bit like arms and legs, but still, even that is based in science because the fluff does help them move.”

Boyer served as an external reviewer of the book and helped Selznick make sure all the science was correct.

“The thing that I really love about the story is that it’s a book that is written for the common reader that focuses first and foremost on plants,” says Boyer. “The plants were the main characters, the heroes of the story.”

Boyer also praises Selznick for letting plants be plants.

“He didn’t want to anthropomorphize plants,” says Boyer. “Brian was vindicating that thought that not only I but many educators have always had in the back of our mind—I think they could write a book without adding little legs and a top hat to them and making them run around like animals, and he not only did it, he did it brilliantly.”

That’s not to say that writing about two seeds this way came easily.

“One of the funny things that happened while I was writing was that I kept using expressions that we often use without thinking, like ‘tears rolled down her cheeks’ or ‘a shiver went down his back,’” says Selznick. “And every time I would have to go back and reread it, because I realized they don’t have any eyes, they don’t have any cheeks, they don’t have a back, there’s no front or back on a seed. So everything had to move [away] from specific body parts that we might use to describe emotions for people, and put it inside the seed, so that we could understand that the character is feeling something inside.”

Once he had approval to write the book, Selznick sent two of the screenplays he’d written to his longtime editor, Scholastic vice president and publisher Tracy Mack.

“I read them, and I was completely swept away,” says Mack. “I don’t think I put [them] down for a second. It was just such an incredible ride and such a magnetic adventure, and I never looked back. I never had a moment’s pause. I just couldn’t believe what luck had landed in my lap.”

Mack’s main role in the editing process was to help with character development.

That meant “really defining their relationship and the dynamic in this sibling relationship,” says Mack, “and then also really creating that character arc, and that emotional arc, and trajectory of the story, and how is each one changed by the other? How do they grow over the course of the novel? What are the catalysts for that growth? Things like that; I think that’s probably where we had the most conversation.”

Mack and Selznick were working together during the height of the pandemic, so they couldn’t meet in person; Selznick was also in Rome during that time. He sent her and Scholastic creative director David Saylor a video of himself turning the pages of a mini book he had created and narrating what the pictures were. She says they made decisions about what art to include pretty quickly.

Big Tree, the resulting 528-page novel, features nearly 300 pages of graphite illustrations, which help advance the story. The book also has a unique look.

“One artistic choice he made that I absolutely love and am in awe of is [to use] the text pages for breathing space,” says Mack. “Sometimes there’s very little text on a page, and it’s almost the way a poet would work. The visuals of the way the words land, not just to your eye, but to your ear...it’s quiet. And [a single] line can resonate, and the reader will rest and take it in.”

The novel spans prehistoric times to the present. It also packs in a lot of scientific information. For example, readers learn that plants really do communicate with one another through their roots. Most of these types of scientific facts are revealed in the book’s afterword.

The book also ends on an optimistic note about the future of the planet. Although Big Tree is a middle grade novel, its story feels universal. Younger children will enjoy the adventure behind it, while the themes about the importance of family and working together will resonate with older children and adults.

“It’s a book that works at almost any age transition, like elementary school graduation, middle school, high school, college,” says Mack. “It’s one of those Oh, the Places You’ll Go!. I feel really proud of that. I think that it is the kind of book that can resonate with different people for different reasons. There’s really something for everyone. The book itself is about community, and I think Brian’s created a book that really is a living example of building community and how important that is, especially now.”

Marva Hinton hosts the ReadMore podcast.

Marva Hinton hosts the ReadMore podcast.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!