Librarianship in 2020: Year of the Go-Getter

This is the time to re-make librarianship in the long term. Here's how some leaders are doing it.

|

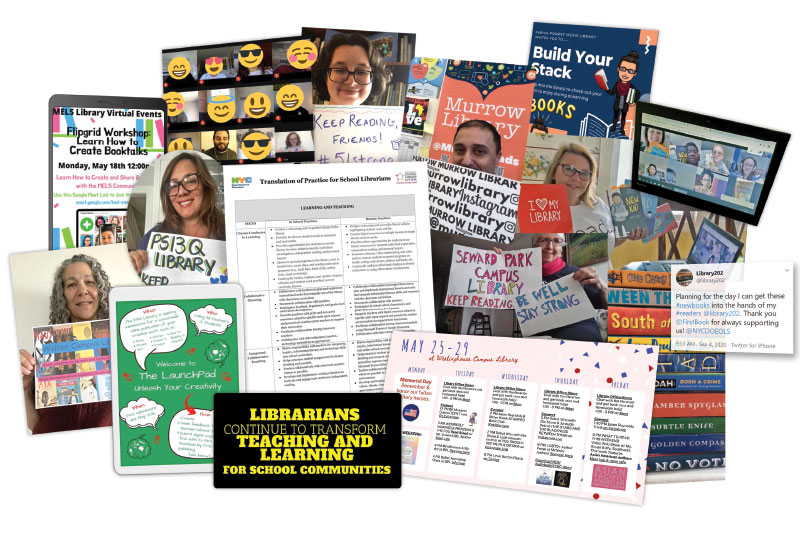

SLJ montage/Images courtesy of NYC School Library System |

When COVID-19 shut down institutions across the country in March, Melissa Jacobs knew that everything about her job was about to change.

The director of New York City’s school libraries immediately saw questions coming into her system’s listserv asking for guidance. “I said, ‘We need to figure this out very quickly.’ How do we do this?”

She took the department’s media program evaluation rubric and rewrote ways to meet all 14 goals remotely, from teaching and learning to program administration. The subsequent document, simply called Translation of Practice for School Librarians, was sent out about a week after schools closed.

The document “took off,” Jacobs says. School librarians told her, “This is the guidance I needed. Now I know what to do.” The Translation of Practice spread throughout the state, and after Jacobs featured it in a webinar, it went nationwide.

“It’s reaffirming to hear from librarians around the country,” Jacobs says. “I’m pleased at how far it extended.”

For school librarians and leaders like Jacobs, now is a crucial time not just to contemplate the future, but to plan for it. Now is the time for change, many library experts say, even as they realize their professional peers are exhausted from trying to replicate in-person services through a variety of virtual methods.

Jacobs, who took the existing school library protocol for the country’s largest school district and rewrote it for today, says librarians shouldn’t expect this transition to be temporary. “I’ve been very clear. Everything we are doing is not just for now.… We have to change for tomorrow.”

“It’s not about what people already use the library for, but how to change the way people are thinking about library services and what that means. The world does not necessarily need the same thing,” says Linda W. Braun, a learning consultant for LEO and a past president of YALSA (the Young Adult Library Services Association).

Since May, Braun and Mega Subramaniam, an associate professor at the College of Information Studies, University of Maryland, have been working with 150 librarians in the COVID-19 Reimagining Youth Librarianship Project. The group meets regularly through Zoom, and Braun and Subramaniam urge participants to push beyond their comfort zones to rethink services for themselves and the profession at large in this extraordinary time.

While this group focuses on public libraries, the same advice holds for school librarians, says Bill Bass, innovation coordinator for the Parkway (MO) School District. Since school went remote in the spring and in-person plans seem subject to change this fall, Bass calls for librarians to use this time of uncertainty to recast their purpose.

READ: The Right and Wrong Way To Make Decisions in a Crisis

“This gives [librarians] the opportunity to think about their role in education differently,” he says. Because school librarians don’t have the same boundaries as classroom teachers, they can “provide authentic, meaningful experiences instead of trying to re-create physical classrooms. Librarians can really help connect the dots for teachers around technology and access to content.”

“As a profession, we’re split between go-getters and the ‘I’m here when you need me’ folks,” says Kristin Fontichiaro, a clinical associate professor of information at the University of Michigan. “This is the year for the go-getters.”

Fighting fatigue, shifting focus

Before diving into ambitious plans, librarians should accept a reality of these times, whether they work at a public building in an urban center, a school library in the suburbs, or a rural library that is the heartbeat of the community: Librarians are overwhelmed.

“The challenge with public youth librarians is they are exhausted,” says Fontichiaro. Many are running curbside pickup and rethinking programs to keep engagement close to normal even when remote. “I’m rethinking how much we can ask of folks when they are trying to tread water. They are at max bandwidth.”

“School starts in two weeks,” K.C. Boyd said in early August. “And I’m tired. I haven’t had a day off since March.” A library media specialist in the District of Columbia Public Schools, Boyd produced five webinars in 10 days, created videos for students, gathered resources for parents, and made sure teachers and students were familiar with remote databases and the tools the library offers.

“I’m beyond tired, but for good reason,” Boyd said. “It’s not about the job, it’s more about the service.”

The evolving service aspect is the focus of those calling for reform. The pitch is basic: If you can’t find a way to rethink how your library operates during a worldwide pandemic, it will never happen. That’s where leadership comes in.

Part of the problem, Braun says, is that too many librarians are laboring to re-create what they used to do. “We’re asking people to think about not who you traditionally serve and who comes into your building, but who might need the library [now] in ways they never had before,” she says. For many people, that means dealing with food insecurity and unstable housing during the pandemic.

The first lesson Braun and Subramaniam are trying to teach is that librarians need to shift their focus, rather than taking on these new tasks while also re-creating typical services.

Instant changes

Boyd’s job changed overnight when her school system went remote. Immediately she began working to connect students and teachers to the district’s databases and public library resources. She and her colleagues supported virtual learning—and also conducted professional development and helped parents navigate online learning. Some were even responsible for device distribution. One of her coworkers brought books, water, and snacks to social justice marches in the city, Boyd says.

The same shift was true for Jennifer Wertkin, director of the Wellfleet (MA) Public Library on Cape Cod. While in the summertime the artsy area swells to 19,000 residents, fewer than 3,000 people live in town year-round, she says. She bought Wi-Fi hotspots to lend to residents because “I consider internet to be a basic human right. Everybody should have broadband.” While pushing most programming online, Wertkin focused on offering simple services such as copying and faxing for residents.

Wellfleet’s youth librarian took story time online and created a middle school reading group. Fluid plans about the reopening of schools have left the library in limbo, ready to work hands-on with teachers if that’s what they need.

In Michigan, where past education spending cuts have dramatically pared the number of school librarians, public librarians were already scrambling to fill the void, Fontichiaro says. Instead of focusing on enrichment and community, youth librarians are teaching about fake news. “To be involved in learning is a big adjustment,” she adds, but pushing into schools while library buildings remain closed is just one way to remind the public of librarians’ importance.

Another way to be proactive, Fontichiaro says, is for public librarians to know a school’s curriculum and work to create lessons, handouts, and resources on a topic. If a teacher is sick or schools suddenly go remote, this work can help plug the gap.

“In Michigan, we’ve been encouraging youth librarians to seize this crisis as an opportunity to make new connections and to try new ideas,” says Cathy Lancaster, youth services coordinator for the Library of Michigan in Lansing. One example is the Michigan State University program Show Me Nutrition, a bilingual education offering for K–8 students. Libraries partner with university extensions to provide six classes in schools to help children make healthy lifestyle choices. Students are even given “ingredient sacks” so they have cooking supplies on hand.

“It is hard in a pandemic that continues over months to recognize creativity or feel like one is doing enough,” says Lancaster. “But I am very proud of the many creative and engaging youth programs I’ve seen from libraries across Michigan, and what I’m hearing from my counterparts across the country.”

Even for librarians willing to embrace a sea change, it can be challenging to convince library administrators that now is the time, says Braun. While striving to rethink their work, librarians are “discouraged if they have these ideas and their administrators aren’t supporting them.”

“We are learning the difficulties in changing mindsets,” Subramaniam says.

John Chrastka, executive director of EveryLibrary (a political action committee for libraries), says school librarians need to remind their coworkers what an effective library does. “If your administration has identified your job as critical, fantastic. If not, you have to be in position to actively advocate for yourself and the work you are doing.”

Bass agrees, telling school librarians, “You can’t wait to be invited. You have to bring solutions from the outset.”

Pooling expertise for public health

Amy Blevins and her colleagues at the University of Indiana fall into the go-getter category. When COVID-19 took hold in March, she was asked to join a team that would do rapid research to answer pressing questions from state leaders. Besides Blevins, an associate director for public services at the university’s Lilly Medical Library, the team has five other librarians, including workers with specialties in health sciences, emerging technologies, and law. Together, the team jumped in, reviewing critical topics such as the sterilization of masks, when infected providers can safely return to work, and the best practices for treating acute respiratory symptoms. The group’s website is open to the public. The team updates answers to public questions as new information and studies become available.

Because this work was done in addition to the team’s regular tasks, and almost always demanded quick action, it was stressful, Blevins says. “It’s a whole new ballgame to do in four hours what we would normally do in a week.”

Because the virus is so new, it can still be hard to find relevant studies, she adds. But when Russia recently approved a vaccine for COVID-19 by skipping its Phase 3 study, she was able to remind officials in her state that typically about half the drugs being studied fail during Phase 3 testing.

This is exactly the type of pivot Braun and Subramaniam are hoping librarians can make in their own communities, be it at school or in a public library.

No matter how circumstances evolve this year, Boyd says one thing will remain true: “We are walking, breathing information hubs. Sometimes we know resources, sometimes we dig. That’s where our skill set comes in.”

Wayne D’Orio writes frequently about education and equity.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Katherine Kelly

"Part of the problem, Braun says, is that too many librarians are laboring to re-create what they used to do." This is only true because we are being forced to do so in the same way we were pre-pandemic. At my school in Florida we have been testing kids since they returned to school in August, quarterly reports are still expected to be written, observations and evaluations are the same (with very minor tweaks), and equity is only give lip-service. All that is cared about is bringing everyone back because the governor and White House wants it so.

Posted : Oct 27, 2020 11:27