Killing the Indians in 2023: Book Banning Seeks to Erase Native Americans | Opinion

Children's literature scholar and author Debbie Reese is keeping track of the many books by Indigenous authors that have been challenged and removed from shelves.

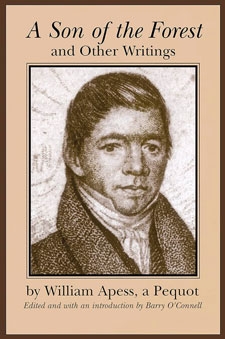

The truth is, we were never uncivilized. But we were depicted that way in children’s books. As far back as the 1820s, Native people objected to those depictions. Pequot writer William Apess, for example, wrote about them in his book A Son of the Forest.

The truth is, we were never uncivilized. But we were depicted that way in children’s books. As far back as the 1820s, Native people objected to those depictions. Pequot writer William Apess, for example, wrote about them in his book A Son of the Forest.

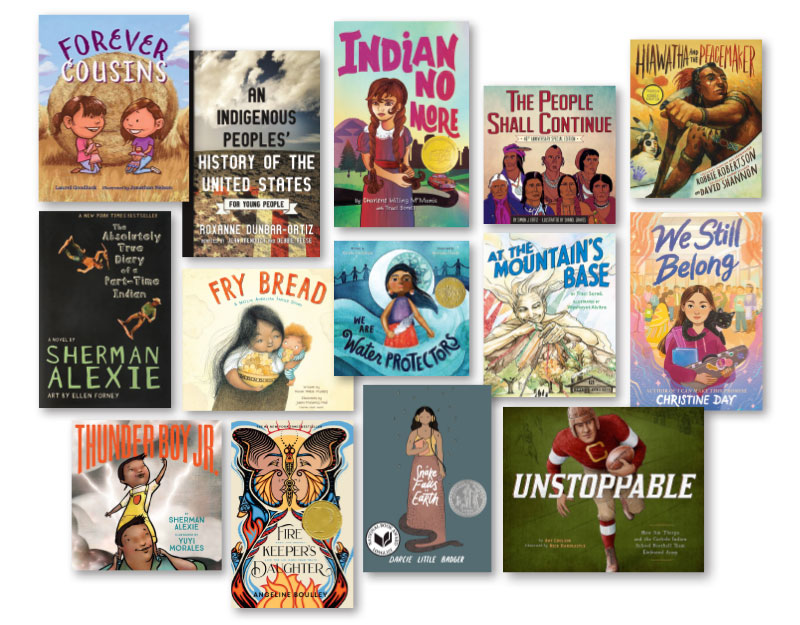

Today—after hundreds of years of derogatory, biased, and factually incorrect representations of us in children’s books—Native parents can reach for books that affirm the lives and histories of our Native Nations and, of course, our children. Those books are by Native writers. With their stories, they are interrupting the cycle of misinformation that has characterized books with Native characters for far too long. And they are bringing forth truths about history that are not included in most textbooks.

Register for Webcast: Webcast: Native Storytelling in Children’s Books with Angeline Boulley, Cynthia Leitich Smith, and Debbie Reese

Let’s look at the picture book Forever Cousins by Laurel Goodluck (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Tsimshian tribal member) with illustrations by Jonathan Nelson (Diné), published by Charlesbridge last year. Its setting is present day, and its main characters are cousins who grew up together in an urban area. In the author’s note, Goodluck tells readers about the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 that moved Native people from their homelands. It is one of many federal programs whose goal was to undermine our nations.

Books by Native writers aren’t just good stories. They are providing non-Native readers with information they have not had access to before.

Today’s book bans are taking those books away from all readers.

I titled this essay “Killing the Indian in 2023” because this movement strikes me as similar to what Pratt wanted done in the 1800s: erase us. In a way, the news coverage of book bans is doing that, too. Books by Native writers and illustrators are not getting much attention in news articles.

To push back on that erasure, in April 2023 I began keeping a log of Native-authored books that are swept up in book challenges and bans. It is my effort to say Pratt was not successful. The federal government was not successful, either. We persevered and will persevere tomorrow, next month, next year, and so on.

The more than 30 books on the list range from Firekeeper’s Daughter, the 2023 Printz Award winner by Angeline Boulley (enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians) to 2021 Caldecott Medal winner We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), illustrated by Michaela Goade (Tlingit).

Also read: Cynthia Leitich Smith’s "Reservation Dogs" Read-Alikes

My own book, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, for Young People, which I adapted with Jean Mendoza (not Native) from the original edition by Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz (not Native), survived a 2021 challenge in York, PA, but is currently banned in some Texas libraries. It was among some 850 titles on a 2021 list compiled by Texas state representative Matt Krause that he said “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.”

Look for books by Native writers—those who appear on that list and others. Ask for these books at the library. Read them yourself. They will enrich what you know about the country known as the United States.

Debbie Reese (Nambé Owingeh) has studied representations of Native peoples in children’s and young adult books for more than 30 years.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!