Philadelphia May See the Return of School Librarian Positions

UPDATE: The School District of Philadelphia has received a nearly $150,000 IMLS grant. The district plans to hire a district director of library science, who will work with the Philadelphia Alliance to Restore School Librarians to build a pipeline for new certified school librarians in Philly and create a five-year plan to restore its school librarian positions, reports the Philadelphia Inquirer.

|

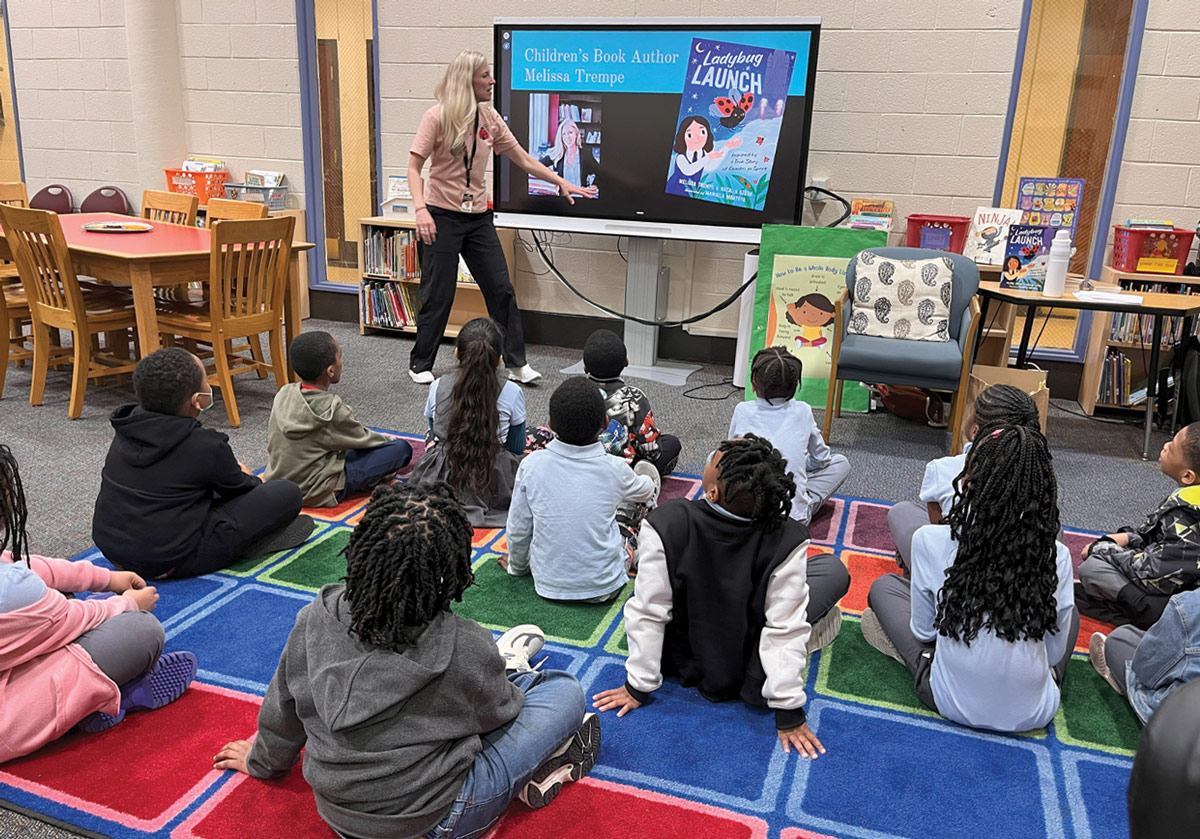

The West Philadelphia Alliance for Children runs library programs in district schools.Photo courtesy of the West Philadelphia Alliance for Children |

UPDATE: The School District of Philadelphia has been awarded a nearly $150,000 grant from the Institute of Museums and Library Services. The district plans to hire a district director of library science, who will work with the Philadelphia Alliance to Restore School Librarians to use the grant to research other large urban districts that have restored or added school librarians and create best practices; build a pipeline for new certified school librarians in the district; and create a five-year strategic plan for Philadelphia to restore its school librarian positions, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer.

[SLJ's June 26, 2024 story:]

For years, Philadelphia school librarians have not seen much affection from the City of Brotherly Love.

Massive budget cuts have decimated the ranks of school librarians, from 176 in 1991 to only four today. That leaves most of Philadelphia’s 216 schools and more than 116,000 students without access to a library, let alone a librarian.

Finally, though, there’s hope. This spring, a job posting appeared for the role of a district director of library science, whose responsibilities will include overseeing all library and digital library programs and services.

While still in the early phase of planning and hiring, according to the district’s office of communications, the new library director position is part of an overall effort to build a comprehensive plan for libraries within the School District of Philadelphia.

“Libraries were an integral part of the district prior to budget cuts and layoffs of librarians,” a district spokesperson wrote in an email to SLJ . “We recognize that libraries can play a vital role in accelerating student achievement, and we are envisioning and reimagining school libraries around the focus [of] accelerating student achievement.”

What this means for the overall future of Philly school librarians is still unclear, but for current librarians and advocates, the job posting has led to cautious optimism.

“I see the creation of this position as a giant step towards restoring school librarians to at least some of our district’s schools,” says longtime Philadelphia educator Loren White.

White teaches at Shawmont Elementary and is currently completing her master’s degree in library science, which she will finish this summer prior to becoming her school’s new librarian.

White’s principal is using discretionary funds to pay for the position.

“Many schools do not have the ability to purchase a school librarian position, since our school district requires schools to have physical education/health, art or music, and technology teachers,” White says. “Small schools with only two or three preparation teachers don’t have the flexibility to add a school librarian. Additionally, most principals in Philadelphia have never worked with or known a school librarian, since they were cut so many years ago.”

Impact of school librarian cuts

It’s difficult to say what impact the loss of librarians has had on generations of Philly students, but library advocates point to research that shows students who attend schools with full-time, certified librarians perform significantly better on reading tests than students whose schools are missing a librarian. Perhaps not coincidentally, most students in the district of Philadelphia in grades 3–8 do not read at grade level, according to 2022–23 standardized test data.

“The longer our district is without school librarians, the more families don’t expect it and don’t know what the role of a school librarian is,” says Bernadette Cooke, one of the rare school librarians in Philadelphia, although her official title no longer reflects that role.

Cooke began her career in 1991 at William B. Mann School, a pre-K–5 school in Wynnefield, a neighborhood in West Philadelphia. After 13 years, Cooke left teaching for two years to go on family leave. When she returned, only a few schools still had libraries. Eventually she landed a job at Julia R. Masterman Demonstration School.

In her time there, Cooke’s position has been eliminated twice, returning once after the school received funds from an anonymous benefactor. After she was cut again, her principal rehired her as an English teacher to ensure job security.

“It makes me really sad that I had to resort to that to maintain my position,” Cooke says.

Yet Masterman is one of the lucky schools to even have a certified, paid librarian on staff. “I am fortunate to be at a school with a vibrant and vocal parent group [that] values the school library. I have also had principals who believed that school libraries were essential and not a frill,” Cooke says.

In other neighborhoods, concerned community members stepped in to ensure students had access to some form of library program. The West Philadelphia Alliance for Children (WePAC) began bringing volunteers to schools in 2003, with a focus on children in grades K–4. Today, WePAC’s volunteer teams work with 12 partner schools, weeding and updating collections, providing at least once-a-week read-alouds and literacy activities, and supplying and maintaining a library cataloging system.

As much good as these volunteer programs have done, the goal remains to return certified school librarians to schools. Jennifer Leith, executive director of WePAC, has yet to hear specifics from the district about the new library director position, but she is excited about what this new role means for the city and WePAC’s future.

“I don’t know how that relationship would work or what they are thinking, but certainly we would want to work with the district,” says Leith. “We started out of a crisis, and if that means the crisis has subsided and we can move on to other book access and literacy work, and the district is willing to take over these libraries and commit to having paid people in it, we’d love that and would help them get to that point.”

Working to bring school librarians back

It will take a major push, however, to fix what might be the worst public school library system in the United States.

“Philadelphia probably has one of the nation’s worst examples of number of students to number of school librarians,” says Debra Kachel, a school library advocate and a core planning member of the Philadelphia Alliance to Restore School Librarians (PARSL).

But advocates like PARSL are working hard to change that reality.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is change perceptions,” says Barbara Stripling, a past president of the American Association of School Librarians and co-founder of PARSL. In addition to combating the stereotype that librarians are simply “book checker-outers,” Stripling says that most parents and community members don’t even realize their schools are missing a librarian.

“We want to flesh out and help them understand what school librarians teach and what the added value of the growth, both personal and academic, of students in the school,” she says.

As part of its mission, PARSL has been working with the School District of Philadelphia to create a long-term strategic plan. This spring, in collaboration with the district’s grants office, PARSL applied for a $150,000 grant through the Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Program to fund a multi-year planning effort to recruit, train, and return certified school librarians to the district.

Through the grant, PARSL will bring together a cohort of 10 urban school districts, including representatives from Boston, New York City, Chicago, Dallas Independent, and Oakland—urban districts that have all begun to restore their own school librarians— “to look at common trends and challenges and what strategies were used to breakthrough barriers,” says Stripling.

Whether they receive the grant or not, advocates know that any real change will be dependent on a school budget that includes school librarians.

“We know you can’t change a whole district or staff all schools immediately, so a strategic plan built with the school district is the best way to approach it, and that includes building up the sustainable funding we know we need,” says Kachel.

Reasons for cautious optimism amid concerns

Advocates and librarians like Cooke are wary, especially since libraries and librarians were conspicuously absent from superintendent Tony Watlington’s most recent comprehensive five-year academic plan for the district.

“Until we, and administrations across the state, view school libraries as necessary to a child’s education as learning math and science, and start passing legislation to support them, school libraries and librarians will always be in danger of being wiped away if money gets tighter or a different administration takes over who doesn’t view school libraries as integral to the school,” says Cooke.

But in addition to the posting for the director of library science position, there are other indications that things might finally be changing.

“Publicly there has been this declaration that school libraries are very important, and signs have been pointing in the direction that [it] is actually on their to-do list,” says Leith.

Currently, there are bills in both the Pennsylvania house and senate that would require a school librarian in each public school in the commonwealth. Although bills like these have been introduced in the past and failed due to budget constraints, a recent ruling by a Commonwealth Court declaring Pennsylvania’s school funding system unconstitutional might finally provide the means for school librarians to be reinstated.

“There are billions of dollars in improvements needed, but the district has been talking about this and it seems like they are putting some thinking behind how to reopen school libraries in Philadelphia,” Leith says.

After years of neglect, soon-to-be-minted school librarian White is hopeful that students across Philadelphia might finally have the same opportunities her students will receive in the fall.

“I am really looking forward to seeing my students’ eyes in August when they enter a redesigned library filled with new books that I have gotten donated and my principal has purchased,” White says. “We will be one of only two K–8 schools with a librarian next year as far as I know. That is inequitable, unjust, and a travesty. Every book should have a reader and every reader should have a book.”

Andrew Bauld is a freelance writer covering education.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!