Healing Reading Trauma and Creating Inclusive Libraries | 2024 SLJ Summit

In their SLJ Summit session, librarians Julie Stivers and Julia Torres provided strategies and suggestions for helping students overcome reading trauma and creating truly inclusive libraries.

In their SLJ Summit session, “For Inclusive Libraries, Heal Reading Trauma,” librarians Julie Stivers and Julia Torres forced attendees to ask themselves some difficult questions and provided strategies and suggestions for helping students overcome reading trauma and creating truly inclusive libraries.

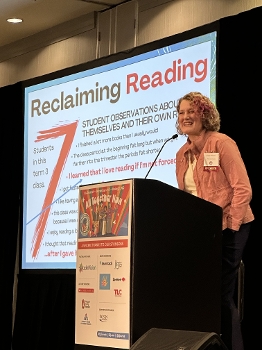

“We cannot run our school libraries on good intentions,” said Stivers, upper school librarian at Carolina

|

Julie Stivers |

Friends School in Durham, NC, and 2023 School Librarian of the Year. “That is not going to work. Then school librarianship is not for us. I'm sorry. Impact matters more than intent—every time, every day, in every moment, every context.”

Acknowledging that they did not use the word “trauma” lightly and are not counselors, Stivers and Torres explained that any student can suffer from traumatic reading practices, but that BIPOC students, English language learners, disabled students, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community are impacted the most. For students whose identities intersect, “the harm can exponentially increase,” Stivers said.

To help heal this trauma, Stivers and Torres said librarians must take an honest look at their practices and make a conscientious effort to undo the structure and programs that create reading trauma, such as being shamed around what is being read, not considering kids’ taste in book choices, but instead spotlighting the same titles year after year; using students achievement as a measure of comparison; and putting time pressures or goals on reading.

“When we think about reading and young people, we have to recognize that? it is not relaxing or restorative if it's done under a time crunch,” said Torres, a public teen librarian. “You're telling someone they need to read 40 pages a night or they're going to be behind.”

That creates toxic stress and impacts the child’s desire to read. Instead, adopt strategies that allow young people to pace themselves.

“I've heard from educators that if they are setting the pace themselves, and they'll go as slowly as possible, because they just want to work the system,” Torres said. “Young people don't care to work the system when they feel the system is working for them. So that's something I want all of us to really think

|

Julia Torres, right, and Julie Stivers |

about. When they feel like we're on their side and we are advocate for them, there's no need to try to game what's going on, because they trust that we really want is what's best for them.”

Reading is relaxing and restorative when it meets individual needs and goals, Torres said. And young people should be involved in setting their own goals and creating a holistic experience that includes satisfying curiosity, entertainment, or being part of a shared experience.

School librarians should also consider broadening their views on what a book club can be. It could be two or three people, include a virtual element with people from another state or country, a listening club where everyone listens to the same audiobook, or a silent book club where everyone just reads without feeling any pressure.

“Open things up for our young people, so they don't just think of a book club as a stereotypical experience,” said Torres.

Stivers stressed collaborations with others in the school, such as counselors or the nurse; and Torres reminded the school librarian audience to look at their public libraries for partnership as well.

“I love to think about our role as librarians and the power of libraries in both macro and micro ways,” said Stivers. “So if we look at this in a very macro way, we might be working with a counselor to do programming. If we're looking at it as micro way, you're reading the book and sharing with your counselor, because you know that they're probably going to get it to a specific student.”

Stivers also shared that she doesn’t call her library a safe space, because she cannot guarantee that. But she does guarantee that she is a safe person, the person students know they can go to when needed.

“Being a soft space to land during the day is vitally important,” Stivers said. “It is not less important than any academic rigor that we are engaged with during the day.”

To make the library space truly inclusive, Stivers and Torres offered these tips:

- Do not sort students (use nongendered terms to address groups of kids, for example)

- Create a collection of titles with BIPOC characters that goes beyond trauma-centered narratives, biographies, and nonfiction

- Do not have traditional book fairs that are book sales that separate students by those who can afford to pay and those who cannot

- Provide students a place to read on their own time

- Do not only spotlight books on BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ communities in their commemorative months.

School librarians must consider who—or what—they are centering each day.

“Do we care about the books, or do we care about the reader?” Stivers asked. “Every time, whether it's policy, whether it's interactions, whether it's a conversation with your administrator, whether it's physical layout, whether it's advocacy, we have to choose the reader every time.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!