Harnessing Data Can Help Strengthen Summer Library Programs

Libraries use data about summer programs to make them better every year, and their methods have been improving.

|

From Left: A Summer Adventure booklet brings smiles at the St. Louis (MO) Public Library; Kids frolic in cool foam at an event with local company Bubble Maniacs at the Aguila (AZ) Branch Library;At the New York Public Library’s Summer Writing Contest ice cream party, kids wrote, created zines, and got to see their work in print.Photo by: Courtesy of St. Louis (MO) Public Library; Courtesy of Maricopa County (AZ) Library; Jonathan Blanc/The New York Public Library. |

This summer, thousands of kids will proudly count the number of books and pages they read, hours spent reading, and prizes earned during summer reading programs, all while enjoying other activities hosted by public libraries over the vacation months. For those well-attended programs that work best, young patrons have research to thank. Behind the scenes, librarians collect and crunch data about summer programs to make them better every year, and their methods have been improving.

“We are always using data to refine, to tweak, and to evolve these programs,” says Alexandria Abenshon, New York Public Library (NYPL) director of children’s programs and services. “If we don’t, they are static and they are not reflecting the kids of today or the kids of tomorrow.”

Abenshon adds that the pandemic was a time of great change and reflection for how young readers learn—and how libraries compile data. Some early COVID-19-era findings and innovations have carried through to inform current programming.

NYPL is among many libraries that use data from the reading app Beanstack, along with paper and digital surveys of their patrons, and feedback from staff and readers, to tailor programs that evolve into better experiences for the patrons and communities they serve.

The kind of data libraries use varies depending on the library’s capacity. But in general there is a mix of both quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative data might include the numbers of participants, books and pages read, time spent reading, number of check-ins to the library, number of ebooks read versus print books, and ratings from surveys and questionnaires. Qualitative data can involve things like formal feedback from library staff, parents and caregivers, readers, and community members; as well as which school districts or neighborhoods participants live in, whether they found the program fun and useful, and what kinds of additional summer programming they may want.

Conversations with library patrons are also an important qualitative data point, says Joe Monahan, manager of youth services for the St. Louis (MO) Public Library (STPL). “In addition to this structured data collection, we also really value the informal observational feedback—what are youth and caregivers saying when they come in? Which programs are getting them excited?” he says.

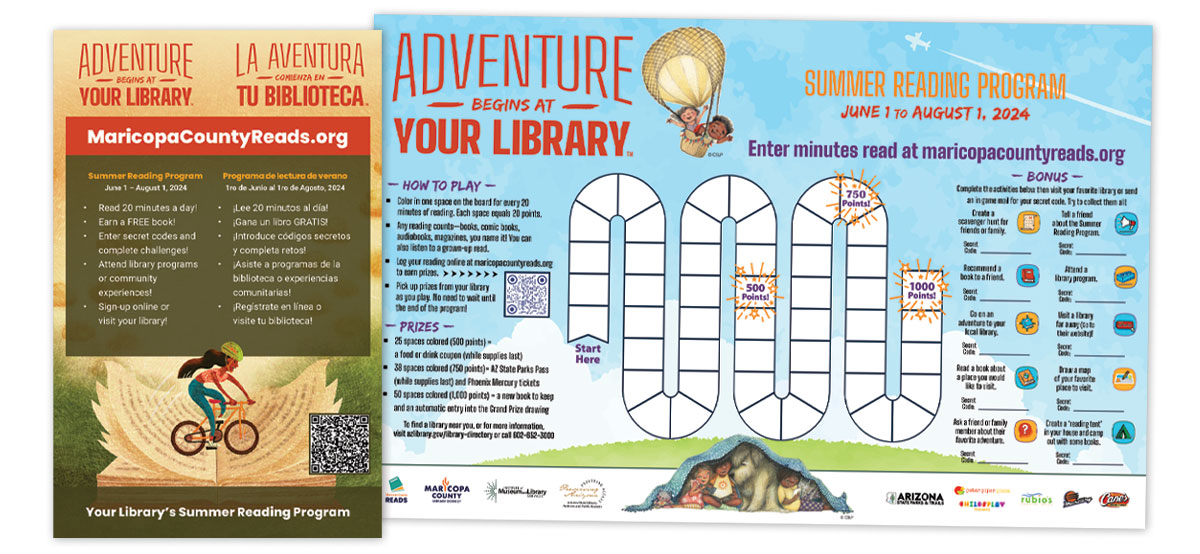

In the Phoenix, AZ, region, Samantha Mears, communications administrator for Maricopa County Library District’s summer reading program, says the library system does not track any student or school district data beyond achievement numbers, age ranges, and whether a child is a new participant. Mears notes that while the general design of the program does not change much from year to year, the program does “use feedback we hear from library staff, messages from customers, and a participant survey to make small adjustments to the program…for instance, creating an ‘all-abilities’ gameboard, creating new marketing materials to explain the program, and adjusting our promotional strategy based on how people are hearing about the program.”

Similarly, the Houston Public Library does not necessarily change the design of its summer reading program itself based on data collected. But it has used data to make “adjustments to improve staff preparation and training to ensure better promotion and higher participation,” a spokesperson says. “We’ve also tailored the types and amount of programming offered each year to align with the annual theme.”

|

A marketing flyer and all-abilities gameboard from the Maricopa (AZ) County Library |

A shift to virtual data collection

There are many ways these libraries collect data on summer reading programs. After the pandemic forced most of the country to learn remotely for several months, public library systems in New York; Nashville, TN; San Francisco; and Houston, to name just a few, have used or now use the Beanstack app.

According to Beanstack, more than 15,000 libraries and schools have licensed the app to use for reading challenges and tools to motivate K–12 readers. The app customizes data based on the librarian’s preferences, and patrons enter the data when they register for a program through the app.

Nikki Glassley, a librarian and summer reading coordinator at the Nashville Public Library (NPL), says the library uses the app to “collect ages, grades, schools, whether or not kids are homeschooled, in private school, or if they’re in public school; we track the number of days that they spend reading, and then we track both prizes that are earned and prizes that are actually redeemed by people coming in to a library to get them.”

Glassley analyzes the data to capture “the big picture.” She can see whether there is a large discrepancy in the number of children registered to participate versus those who actually use the app to track their progress. Glassley uses that to gauge interest in the program and what changes might need to be made.

With this type of dataset, her team was able to redesign the program to fit patrons’ needs post-pandemic—specifically, streamlining the program. Glassley says that while NPL is still navigating how best to collect patron feedback, staff surveys are an important source for program design.

“We ask staff how they felt about their ability to explain the program. Did they feel like it was something that was really simple? Could you explain it to patrons in one or two sentences? We were hearing from staff that we were really over complicating things,” Glassley says. “The number of optional activities were confusing patrons who just wanted to pick a book or audiobook, and taking away time from interacting with patrons beyond just explaining the program.

“We went back to a lot of basics, really trying to focus on the message of reading and the importance of reading, making that message as simple as possible for patrons to explain or for staff to explain and for patrons to understand,” she adds. “And we saw a 40 percent increase in our participation…the biggest increase that we’ve had in six or seven years.”

NPL also uses the data to guide the work of its outreach librarians, who partner with school librarians and talk to students about the summer programming in neighborhoods and school districts with lower registration or participation in the program. The library saw “a huge increase in the number of public school students who are participating as a result of those visits,” Glassley says.

At the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL), Michelle Jeffers, chief of community programs and partnerships, and Alejandro Gallegos, community engagement manager and Summer Stride co-chair and data lead, also started to use Beanstack during the pandemic to reach patrons virtually. Jeffers says there are some drawbacks to using the app, because the demographic data is input by the patron, who may not share accurate information about zip code or age to protect their privacy. This can skew some applications of that data when it comes to determining which neighborhoods or school districts have low participation, particularly since SFPL’s summer reading program involves all ages.

Gallegos sees the app as a complementary tool. “We’ve always had a paper tracker to go along with our Summer Stride program,” Gallegos says. Based on detailed surveys and feedback from staff about how patrons, parents and caregivers, and children are interacting with the app and the paper trackers, SFPL now has several options available for participation. To capture as accurate data as possible, Gallegos says patrons can fill out a paper form first and have staff help them register for the program through the app using the data from the form.

Abenshon says the appeal of the app to capture data “is that there’s a lot of data that you can get from [it], and that was really exciting. The opportunity to get badges to gamify reading [with Beanstack] is really powerful, and we’ve talked to many of our colleagues in other systems who have leveraged that.”

However, as the city opened back up, Abenshon says the library saw a large drop in the number of patrons using the app because they preferred to come into branches and use manual trackers, which can feel more interactive and personal. For example, some have large murals children create with library staff, noting the participants’ names and number of books read; others have paper trackers.

SFPL also has a system-wide research and analytics unit that tracks which branches books are checked out from and returned to, the most popular titles, and the most popular languages of the books. Gallegos says the unit is “using some of this summer data and overlaying it to get like kind of a deeper, more analytical picture, less anecdotal” about the program. And like SFPL, NYPL and Nashville conduct staff surveys as a means of redesigning programs. These pieces of feedback are subjective but crucial to tailoring programs not just for each library system, but for each branch.

While electronic surveys and apps may work for many library systems, youth services administrator Christine Caputo of the Free Library of Philadelphia (FLP) says that isn’t effective for their city. Caputo says the staff “tends to do paper-based surveys because we’ve tried to do electronic things, and we’ve got a big digital divide” among patrons and between underserved neighborhoods and areas where the library is accessed more.

Caputo also explains that “hyperlocal programming” is how FLP operates. “It could be one part of the neighborhood is well-connected to the library, but another part is not as well-connected, [so] some of the outreach programs that we do in order to try and reach those really smaller segments of neighborhoods” are driven by staff and parent/caregiver survey data conducted periodically and at the end of the summer. “We [also] have half-page surveys for kids to give feedback, mostly about the individual programs and activities,” Caputo says. “They have smiley faces and frowny faces on them, so that the youngest kids can also participate.”

Philadelphia was no exception to the changes experienced during and after the pandemic. “Over the last several years, we’ve really been rebuilding and reconnecting with communities and with individuals,” Caputo says. “We have a huge literacy challenge in Philadelphia, as other big cities do, and so one of the things that we’ve done is to try to double down on some of our engagement with literacy and with literacy organizations” in the wake of the pandemic.

Caputo explains that the city’s McPherson Square Library is located in a small park frequented by drug addicts and some of the city’s unhoused population and had traditionally lower enrollment in summer reading programs. Partnering with the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department, Caputo says they were able to “build a new playground in that square, and fenced it in. They have a city department that comes out and cleans the park every morning from all the needles and debris so that the kids have a place in the summertime they can come and be kids and they don’t have to worry about the dangers.

“That library has become a focal point for what other kinds of services and programs and materials that need to go to that community,” Caputo says, including play activities run by the Parks and Recreation Department, addiction counselors who speak with the park’s unhoused population, and community groups who help people access housing and public services.

|

Strip 2: From Left: Stocking up on free books at a St. Louis Public Library Summer Adventure event; The Free Library of Philadelphia’s 2024 Summer of Wonder kickoff event.

|

A new survey across libraries

The National Summer Learning Association (NSLA) also collects key data that library systems could use to redesign summer reading programs, says Elizabeth McChesney, former Chicago Public Library systemwide director of children’s services and family engagement, who now serves as a senior adviser to NSLA. McChesney helped write the short NSLA survey, created in 2024, which is comprised of questions about whether parents/caregivers agreed that summer activities at the library help motivate their child to read and learn, whether participating in summer activities through the library helped prepare their children for the next school year, and what parts of their library’s programming the caretakers enjoyed most.

Participating library systems included those in St. Louis, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and central Arkansas. “The results were aggregate for the survey,” McChesney says. “Each library ran their own surveying and gave me their data, which was compiled.” She notes that while “NSLA doesn’t create library programming, per se…we do talk about ways that libraries may want to deepen their work based on our evidence and experts who come in and talk with us.” The survey results were presented at the NSLA’s National Summit last fall.

“When the library leaders talked about this on a panel at the summit, they all said they learned a lot about their communities and what parents’ dreams are for their kids,” McChesney says. And the survey results revealed more than just program participation or the number of books read. It showed that “parents love the reading programs but seek out STEM and tech programs right alongside it,” and “libraries report an uptick in interest in free programs every year.”

Using data from its own patron and staff surveys and the multi-system NSLA survey were some of the reasons SFPL is offering more outdoor, family-friendly programming during the summer. It currently partners with the National Park Service to plan field trips and guided tours of the local national parklands, which many patrons had never visited or knew was accessible. Gallegos says, “Part of our mission is to open up people to new experiences.”

Driven by participants’ preferences and research, STPL “marked a major overhaul of our approach to our summer learning program” in 2024, Monahan adds. The library system partnered with the St. Louis County Library to offer a combined summer learning program throughout the whole region, in which participants could choose what programs to engage in and which books to read based on their interests, rather than being assigned them. They also “placed a great emphasis on drawing in St. Louis’ amazing local museums and learning institutions to serve as partners in the program.”

Monahan adds that the NSLA data cemented what the STPL was learning from its own patron and staff surveys: “It really showed how the library can be important to kids and families in many different ways, depending on their needs.”

Mythili Sampathkumar is a freelance journalist based in New York City.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!