Going the Extra Mile: Equity in Summer Programming

These public library programs reach out to all kids.

|

|

|

From the left: Kids at the Mendoza Dairy in Point Reyes, CA, get ready to read, play, and learn with the Learning Bus/El Bus Del Aprendizaje; Part of Marin County Free Library’s Reading on the Ranches program.Courtesy of the Marin County Free Library |

|

For nearly 25 years, pairs of teenage interns have fanned out to dairy ranches in Northern California during the summer to bring books and games to the workers and their families through a program called Reading on the Ranches.

The six-week program is sponsored by the Marin County Free Library (MCFL). The interns are former participants in the program, which primarily serves Latinx farmworkers.

“Our rural populations definitely have difficulty reaching the physical library for many reasons, lack of transportation being a big one,” says Madeline Bryant, senior librarian and manager of four West Marin branches.

Increasingly, public libraries are implementing summer programs like Reading on the Ranches that center equity. The idea is to make sure the services provided are reaching marginalized groups.

It’s not enough to have a popular summer reading program if the only kids who participate are white and affluent. A summer STEM series isn’t really a success if all the participants are boys, monolingual, able-bodied, or neurotypical.

|

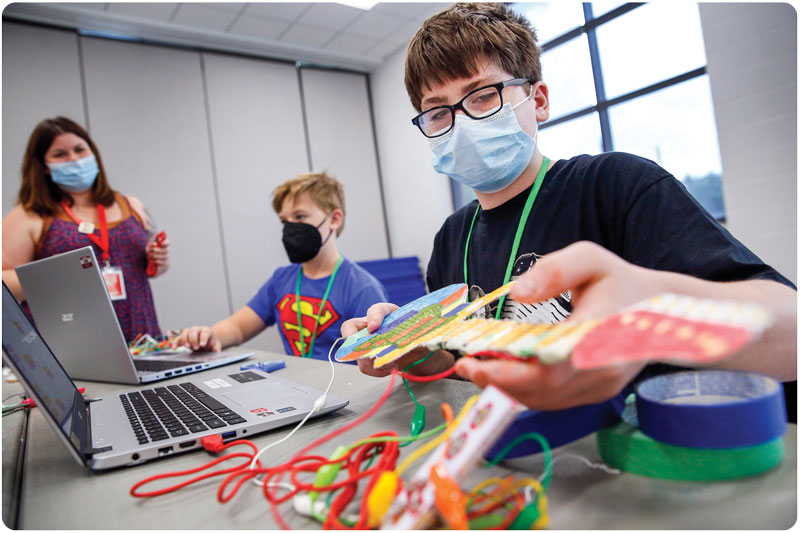

A STEM camp at Cedar Rapids (IA) Public Library, also a ULC partner.Photo by Jim Slosiarek/The Gazette. Used with permission. |

“When we really hold equity, we are reminded that there’s something in common that we’re working toward, and in doing that, folks need different things, different supports, to get to that same goal,” says LaKesha Kimbrough, a healing-centered equity consultant who worked on the California Library Association’s Building Equity-Based Summers initiative.

The goal of most summer programs is to keep children reading over the summer. But to make that happen for everyone, different supports are needed. For the families served by Reading on the Ranches, supports provide a way to physically access books. The dairy ranches where these families live are at least an hour outside of town, and many families rarely come into town.

“It’s such a treat for families who are isolated,” says Bryant. “It’s kind of like when the ice cream truck comes by. It’s the joy when you see a bookmobile or a van and you know that there’s something waiting for you there and that someone’s going to speak your language and bring this welcoming service to you.”

The library staff hopes these visits encourage the families to visit one of their branches in person at some point. The interns see the families when they visit the ranches and choose books accordingly. So if there are a lot of teens around, they bring books that would appeal to that population. If there are many toddlers, they’ll bring more picture books. Bilingual books for toddlers and young children are popular choices, while teens prefer graphic novels, and many of the adults are interested in cookbooks.

“I think the reason this program has been so successful for 20-plus years is those relationships with staff,” says Lana Adlawan, MCFL director of county library services. “We have been respectful, thoughtful, and meet family’s needs without any expectations of them changing what they need to meet our needs. It’s all about them.”

Serving farmworker families fits naturally into the library’s mission to be inclusive and welcoming to everyone in the community. In 2018, MCFL, along with the Santa Monica Public Library, started a pilot program for all California libraries to train staff in Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) practices. GARE is a national and regional network of government workers who are striving to achieve racial equity.

Marin County library staff is in the process of looking at their mission to make sure it still aligns with GARE practices.

“We’re doing our strategic plan through a racial equity lens, putting our resources, budget, and goals in line with the work that we are doing with our communities,” says Adlawan.

|

Kids prototype solar-powered homes at the Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County (OH), an Urban Libraries Council partner.Courtesy of Urban Libraries Council. |

A partnership for reading

In some communities, equity-based summer programming leads to efforts to help students perform better in school.

READy for the Grade is a program in Connecticut that works to prevent summer learning loss for kids in low-income families through intensive work on reading. The program was created by NewAlliance Foundation, a nonprofit that provides grants to public libraries for summer reading programs. Six libraries across the state participate, and each library decides how to run the program in their community.

The program serves children in kindergarten through third grade; the latter is a pivotal year for students. Studies have shown that students who don’t read well by third grade are at risk of not graduating from high school.

“The chances of a young person dropping out of high school, or getting into trouble, or graduating without being able to read doesn’t create much of a future for them. So the program is trying to catch the problem, in essence, before it gets that bad,” says Maryann Ott, executive director of NewAlliance.

The Brundage Community Branch of the Hamden (CT) Public Library System (HPLS) hosted the program for the second time last year. The branch is located in an economically distressed area and is within walking distance of three schools that meet the qualifications for the program.

“This branch has not been as well used as it could have been, and so when this grant came along, I thought this is an opportunity for us to revitalize the branch as a community anchor in a very densely populated part of Hamden,” says Melissa Canham-Clyne, library director for HPLS.

Libraries in the program partner with local schools to identify students who would benefit. Most of the libraries offer one-on-one tutoring, as well as small-group reading instruction and other activities that support literacy development. An independent evaluator visits each library and determines if it’s meeting the goals of the program through pre- and post-test scores. In the vast majority of cases, students either improve or maintain the reading skills they had prior to the program.

At the Brundage branch, students came to the library once or twice a week for reading instruction over six weeks in the summer.

“Almost every parent wants more—more hours, more days,” says Marcy Goldman, the head of children’s services at HPLS. “We had one family express such gratitude to the teachers. Their child was so behind, and somehow in the six weeks over the summer was able to learn to read after not getting it for an entire year at school.”

The children’s families were also invited to participate in the program. Last summer, two in-person events were held for families along with five online events. Parents and guardians were also able to communicate with the children’s tutors to check on their progress or find out how to help them with their reading at home.

Outreach is a big part of the program. In 2022, the Brundage branch surveyed local children in third through eighth grade to find out what they thought of the library. They found 34 percent of the children in Lower Hamden didn’t have a library card or even know there was a library in their community.

“We actually have two libraries that they could walk to, so it was a real eye-opener,” says Canham-Clyne.

The library took that information and used it to request funding from community groups; the money is going toward field trips.

“So now we are paying for the schoolchildren during the school year to come to the library to get their library cards made,” says Canham-Clyne. “And to say, ‘Here’s the library. It’s a magical place.’ And also to work on dispelling what we heard in some of our surveys and community conversations—we still see the library as an elitist institution or as a white space. We’re really trying to fight that as much as possible.”

When it comes to considering equity in programming, the president and CEO of the Urban Libraries Council, Brooks Rainwater, says this type of community partnership is vital, and it doesn’t have to be overly complicated.

“The primary advice I would have is to look at your existing programs and think about how and whether they’re serving the whole community. Really key in and focus on historically excluded communities, thinking about ways that we can lift up children of color as well as those [who] are disabled,” says Rainwater. “Having that holistic approach can make an incredible difference.”

|

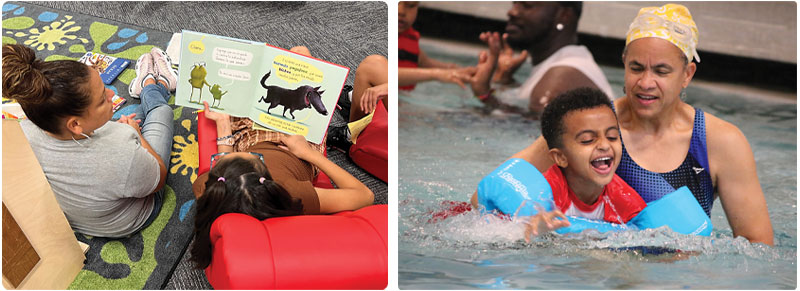

From the left: An instructor and child at Willimantic (CT) Public Library participate in the READy for the Grade program. Courtesy of New Alliance Foundation; Camp Read-A-Rama cofounder Michelle H. Martin connects reading to activities like swimming. Courtesy of Camp Read-A-Rama |

Camp Read-A-Rama

In Washington, the Spokane County Library system and Sno-Isle Libraries have teamed up with a University of Washington professor to offer a reading camp.

Michelle H. Martin is the cofounder and board chair for Camp Read-A-Rama, a day camp that ties reading to traditional camp activities. She is also the Beverly Cleary professor for children and youth services in the Information School at the University of Washington and exclusively teaches pre-service librarians.

Martin, who also serves as the program chair for the school’s MLIS program, started Read-A-Rama in 2001 when she was a professor at Clemson University in South Carolina.

“I just thought it didn’t make sense for me to be a children’s literature scholar and not be making a difference in the community when children’s literature really lends itself to community outreach,” says Martin, who holds a PhD in English.

She turned the event into an assignment for her students. They learned how to do an effective read-aloud with young children that accompanied some sort of activity related to the book. Every child who participated got to take a book home. After running this program for seven years, Martin teamed up with another Clemson professor, Rachelle Washington, to teach a course called Ethnic Children’s Literature and Camp Read-A-Rama. She and Washington developed the camp into what it is today.

“Then I also—being a lifetime Girl Scout—taught the students about how to take the kids on a hike and connect it with books, how you take them swimming and connect it with books,” says Martin.

They ran the program for five years. When she took a job at the University of South Carolina, they continued it from there for another three years. The camp became a nonprofit organization during this time, and it made the transition with her when she moved to the University of Washington in 2016.

“Right now we are in the process of trying to train librarians, teachers, school youth group leaders, whoever is wanting to roll up their sleeves and help improve childhood literacy in the U.S.,” says Martin.

A big part of the camp is encouraging kids to incorporate books into every aspect of their lives.

“It’s about, as we say, helping kids learn to live books,” says Martin. “So everything you do, there’s a book you can connect it with, and every book you read, there’s something you can do to help you enjoy that book more.”

Achieving equity has been a part of the program from the start.

“I have always positioned Camp Read-A-Rama in communities that need us most,” says Martin. “I think Read-A-Rama is good for every child. But we really have a passion for reaching the kids whose parents maybe don’t speak English or maybe have some literacy challenges themselves.”

The program also takes steps to help children who are living in poverty. Some of the camps provide breakfast and others provide swimsuits so that every child can participate in swimming.

The camp’s focus on equity also comes into play with the books selected.

“We base the curriculum, not exclusively, but primarily around books by BIPOC authors, and books that feature children with disabilities, that feature children who are Black and Brown, children who are from other countries besides the U.S.,” says Martin.

A daunting goal

While many librarians agree that equity should be considered when it comes to programming, taking on initiatives like this can be daunting, especially today, when some conservatives treat equity like a dirty word.

For that reason, Kimbrough says, some of her library clients choose to avoid that word and talk about increasing access to the library instead. Others want to start taking equity into consideration, but the task can feel overwhelming.

“There’s no checklist for equity work,” says Kimbrough. “There’s no finish line for equity work, and that can be scary.”

She says others are held back by fear that they’ll make mistakes.

“My encouragement is to think about, What are we learning as we’re doing this work? Because there’s no such thing as perfection,” says Kimbrough. “We’re human. We’re wonderfully flawed, so we’re all going to learn and grow.”

Marva Hinton hosts the ReadMore podcast.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!