Bearing Witness was an Act of Patriotism Then, and so Necessary Today. Tell Your Story. | From the Editor

She was a bit shaky at first but persevered through nerves and emotion to tell her story. My mother's testimony bore witness to injustice. Stories matter.

She was a bit shaky at first but persevered through nerves and emotion to tell her story.

She was a bit shaky at first but persevered through nerves and emotion to tell her story.

“My name is Mary Ishizuka and I am here to speak on behalf of my brother and four sisters—and in memory of our parents, Kuichiro and Hiro Nishi.”

Leaning into a microphone centered on a witness table, my mother proceeded with her testimony, delivered before the federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), at the State Building in downtown Los Angeles.

It was August 5, 1981, and I was there to hear mom talk about her father, who came to the United States in 1905 at age 19. Through perseverance and hard work, she recounted, he saved enough to lease a small bit of land and build a nursery, first in Pasadena. In the 1930s, he cleared a grove of orange trees at Wilshire and Sepulveda and on these 20 acres he raised specimen trees on what became one of the largest nurseries in LA. Grandpa also built a home for his family and served as a leader in his community and the Buddhist church.

“All that changed the night of December 7, 1941,” said my mother. “Two FBI men came to the door and went directly to his bedroom and were taking him out the door with his night clothes on. We asked that he be allowed to change into a suit—they gave no explanations as to why he was being taken or where he was going.” He was brought to the police station, the family learned later, then to a federal prison on Terminal Island, after that a detention center in Missoula, MT. They did not see him for over a year.

I knew, or thought I knew, the event, the basic facts of the incarceration. What I didn’t know was the story—his, the family’s, and that of my mother. That was typical of the Nisei, my parent’s generation, who didn’t speak about the “camp” experience with their children.

So, it was initially difficult to get witnesses before the CWRIC, a bipartisan commission mandated by Congress under President Jimmy Carter to investigate Executive Order 9066, which led to the exclusion and incarceration of all West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry in 1942.

With the support of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and the grassroots National Coalition for Redress and Reparations, more than 750 witnesses brought their testimony to 11 hearings held nationwide, from San Francisco to Washington, DC, and Chicago. For many, it was the first time they had ever spoken about what happened to them.

|

|

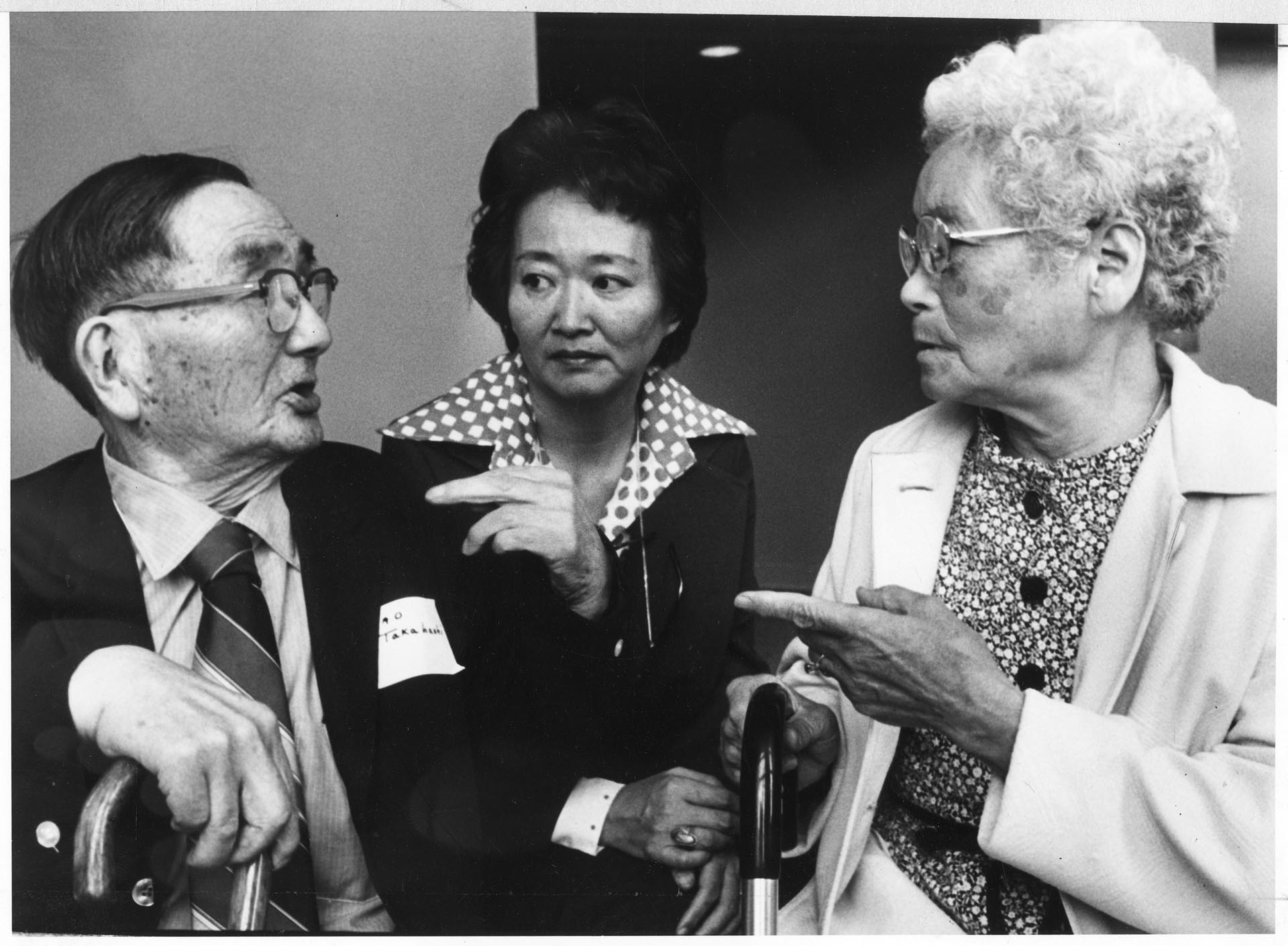

Masao Takahashi, left, and Hotoru Matsudaira, right, discuss their wartime incarceration. Translating their conversation at the CWRIC hearing in Seattle is Takahashi's daughter, Mako Nakagawa, center. September 11, 1981. Source: Densho Encyclopedia |

After receiving these accounts and further interrogation of historical records, the CWRIC published “Personal Justice Denied” in 1983.

With no evidence of espionage or sabotage and lacking military necessity, the evacuation, concluded the report, resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” It went on to recommend a public apology, $20,000 in individual reparations to survivors, and funding for related education, stating that “...nations that forget or ignore injustices are more likely to repeat them.”

The CWRIC findings led to the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. They also spurred the coram nobis cases of Fred Korematsu, Min Yasui, and Gordon Hirabayashi, which resulted in their wartime convictions being overturned. The hearings also enabled Japanese Americans to see “the power of collective action,” JACL’s Harry Kawahara told the Nichi Bei News.

Bearing witness was an act of patriotism then, and so vitally necessary today. Tell your story.

Of note in this issue: Librarian accounts of COVID. See "Finding Our Way: How We Navigated the Chaos and Challenges of COVID-19."

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!