Teaching Research Skills Through Game Theory and a Murder Mystery

In an attempt to make teaching research skills less "dry and boring," this middle school librarian hit on a mysterious new lesson plan, and the strategy has been a huge success.

|

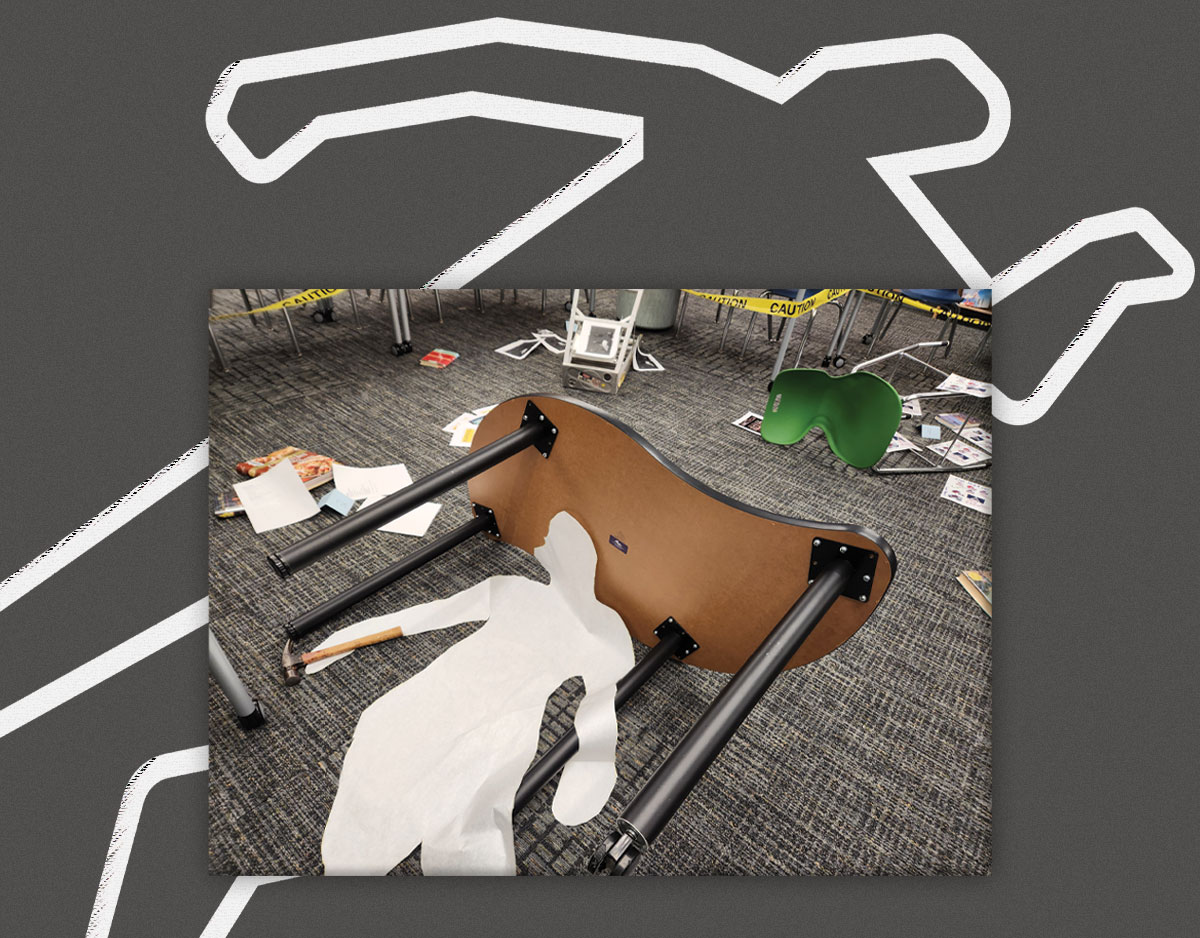

The crime scene in Ertelt’s library.Photo courtesy of Tobye Ertelt |

For a school librarian, “the spark” can come from connecting students to books they love or successfully collaborating with classroom teachers. It’s the moment your thinking—and the possibilities for learning—expand.

When I became a school librarian, I wanted to pull students into their learning. About 11 years ago, two things collided in my mind and started my journey. It started with an eighth grade social studies class. Before me, the teacher had created a four-week unit on the Oregon Trail. Because of a new curriculum and time constraints, the unit needed to change. At the same time, I was learning about game theory. Bam! The spark hit me. I took the social studies teacher’s Oregon Trail lesson and gamified it. I made a choose-your-own-adventure where the kids focused not only on learning about the trail but also life skills, decision-making, consequences, and teamwork.

After that successful unit, I looked for more opportunities to bring game theory and simulations into my collaborations. The lesson in need of such a transformation jumped out at me almost immediately—research skills. While vitally important, research skills are, unfortunately, dry and boring. I was pondering how to bring a fresh approach to the lesson while enjoying one of my crime-junkie television shows when it hit me: Why couldn’t I create a murder mystery in which students use research skills to solve the problem?

First step, find an ELA coteacher as excited as me, who was willing to try. The next day, I started sketching out the lesson, and I reached out to one of the ELA teachers. My starting line: “I have a crazy idea.” Instead of laughing me out of the room, she worked with me, and we planned the perfect murder mystery project.

We begin our weeklong unit with a day focused on defining, giving examples, and class discussion on how to evaluate the lesson. We use ABCD (Author, Bias, Content, Date), but you can change the work to fit whichever method you use: CRAAP Test, SCARAB, RADAR. At the end of the first day, we explain that investigators use the same methods to investigate a crime. Then we introduce the murder with me as the victim.

The next two days consist of the students using multiple sources (suspect statements, eyewitness statements, and the crime scene) to solve the murder. The suspects are fellow teachers and administrators. I originally sent an email explaining the project and what they were being asked to do. Since the first year’s success, I often have so many volunteers, each class has different suspects. I create silly, nonthreatening motives and personas to answer questions about our friendships, what made them mad, and where they were during the window of my murder. All staff are given their statements in advance and cannot add to them “on the advice of their lawyers.”

Eyewitnesses are historical and literary characters played by students. Their statements support or invalidate the suspect statements and crime scene evidence.

At the end of the second day, the teams must make a ClEaR (Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning) statement on who they think is the murderer. From our first year to today, the greatest part of this lesson is the level of student engagement. They are so involved and excited, which gets the staff engaged, too.

The accusation moment is amazing. The holes in their theories become clear, and they see their bias. Almost every year, we have at least one class that completely gets it wrong the first time because “that teacher is too nice to murder someone.” In those cases, we allow them a few minutes to reexamine their evidence and make a new claim. After the arguments and revelation of the murderer(s), we have them reflect on what went well and what they missed during their research that led them to their accusations—even if they guessed the correct murderer.

The final two days of the project focus on individual assessment of their understanding of the research skills. Our students use materials from Bespoke ELA and must answer, “Is Lizzie Borden innocent or guilty of murdering her parents?” They formulate an argument using primary and secondary sources. We don’t allow technology, so they can’t look up what happened to Borden. After they write a ClEaR response, we reveal Borden’s fate.

The success of this unit led to many other gaming and simulation lessons. I have cotaught lessons on the Black Death, ancient civilizations, and the Silk Road. Each successful lesson provides a new spark and increases my commitment to creating engaging work.

Tobye Ertelt is the digital teacher librarian at Oberon Middle School in Arvada, CO.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!