Absent Live Events, Publishers Keep Creators and Librarians Connected

COVID has changed the way publishers promote books—and how libraries buy them.

|

Darcie Little Badger and Levine Querido senior editor Nick Thomas at a BookExpo event.Photos courtesy of Levine Querido |

Book tours. In-person networking at conferences. Physical mailings. All gone in an instant. COVID has changed the way publishers promote books—and how libraries buy them.

Events on Instagram, Crowdcast, and other platforms are here to stay, marketing directors say, in large part because they draw a much larger school and library audience online than is possible in person. The focus is less on swag, more on deep connection with readers. Since librarians can tune in from anywhere for free, a broader, more diverse group is engaging and providing feedback.

“If I had shown you my marketing plan in January, it would have been all [live] events,” including author bookings at the American Library Association (ALA) and Public Library Association (PLA) conferences, says Antonio Gonzalez Cerna, marketing director at Levine Querido. “In two weeks, everyone had to learn how to create web events and make them successful in a completely different way.”

Little, Brown Books for Young Readers (LBYR) released Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds just as the lockdown went into effect, says Victoria Stapleton, director of school and library marketing. The publisher’s marketing plans for the book had included appearances at the Texas Library Association (TLA) annual conference and SXSW EDU. “It became clear that online events would be very advantageous to getting the book out,” Stapleton says. In tune with the times and the nation’s focus on racial justice, Stamped hit best seller lists.

Once the TLA and ALA events went virtual, “we had to quickly pivot,” says Michelle Leo, vice president, director of education and library marketing at Simon & Schuster. The publisher offered an “ALA in a Box” promotion, where librarians could choose e-galleys or a select number of physical galleys. Simon & Schuster has also participated in webinars from SLJ, Booklist, and Junior Library Guild, Leo says.

|

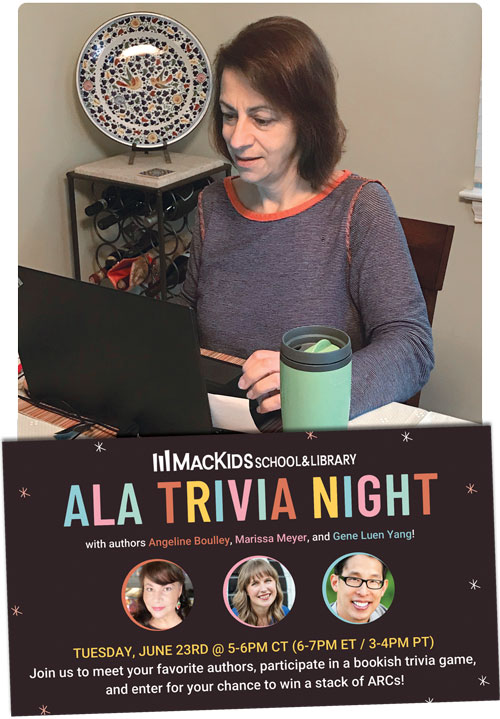

Macmillan’s Lucy Del Priore in her home office and a MacKids promotion.Photo courtesy of MacKids School & Library |

Virtual conferences have been a good opportunity for Linette Kim, library marketing manager at Harlequin’s Inkyard Press imprint. “Because I’m a team of one, I can focus on quality rather than quantity,” she says. With live panels off the table, she is pitching authors to participate in virtual events including Instagram Live and Instagram takeovers.

In addition to participating in virtual events, Random House Children’s Books has produced its own author webinars and, like other publishers, is providing librarians access to electronic ARCs through Netgalley instead of mailing physical ARCs, says Adrienne Waintraub, school and library marketing director.

Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group launched the MacKids School & Library website a year and a half ago and was prepared for the virtual pivot, says Lucy Del Priore, director of school and library marketing. The site tells users what’s available on NetGalley and offers staff picks, downloadable kits, and teacher guides. A permanent “virtual booth” supplements conference offerings. The average number of people using the site rose from 400 last year to some 2,200 currently, and subscriptions to a revamped e-newsletter grew from 40,000 in 2019 to 75,000. The publisher also offered a MacKids Streaming Schoolhouse over the summer for children stuck at home, with illustrators giving art lessons and authors presenting on science and other topics.

Connecting with a more diverse audience

Gonzalez Cerna is seeing more BIPOC librarians virtually, as well as “more engagement from a lot of younger librarians who are already active online and social,” he says. Leo also says that virtual events have been reaching new teachers and librarians who can’t afford the time off or the travel costs of attending a conference in person.

In addition to attendees’ financial limitations, only so many people can fit into one physical conference room, Stapleton notes. She’ll still bring authors to conferences in the future, “but I want to lean into how we can bring rich, interesting, beneficial conversations to our audiences by whatever means are available to me,” she says.

Like other publishers, Random House typically holds a New York–area preview every season for librarians. Now, “We’re reaching a lot of people that weren’t able to travel to conferences or weren’t in New York,” Waintraub says. Similarly, Macmillan’s Book Buzz preview events, previously limited to the tri-state area, are now open to virtual attendees nationwide. Attendance has risen from 60 or 70 to several hundred, says Del Priore.

Random House newsletters and social media handles “have really become our way to communicate with people,” adds Waintraub. “People want to interact with us, want to have these conversations. And if they have to have them virtually, we’ll do it virtually.”

The tradeoff, says Gonzalez Cerna, is the lack of personal interaction. “Your job is to be out there shaking hands, saying hello, remembering the names of all the award committee people, remembering the names of all the influential librarians.…And now it’s bittersweet, because you don’t really get to have that face time with them.” Gonzalez Cerna relies a lot on tweets, emails, and comments on Zoom chats for librarian feedback. Virtual appearances by Levine Querido’s authors and illustrators have included drawing demonstrations on Instagram and online readings.

Inkyard Press has also expanded its newsletter outreach and subscriber count. Because of safety measures at the warehouse, Kim can’t fulfill as many requests for physical mailings as she used to. “I’m more intentional with the galleys I do mail, and they’ve been packaged up as care packages,” she explains, which are then sent to librarians’ and educators’ homes.

|

Michelle Leo of Simon & Schuster working remotely.Photo courtesy of Michelle Leo; Simon & Schuster |

Deeper connections

The focus now, Stapleton says, is on meaningful conversations around books and how they resonate with readers. A recent online event on class and economic anxiety in middle grade books featured LBYR authors Julissa Arce, Jen Torres, and Tony Abbott. “We don’t see a lot of books that deal with [economic anxiety],” says Stapleton. “But the situation with COVID has definitely exacerbated that, because so many people in so many areas have lost their jobs. And educators and librarians are being called upon by their communities to serve these readers.” The publisher encourages deeper conversations through a podcast series as well.

Leo says that Simon & Schuster’s virtual offerings, like other publishers’, include allowing online read-alouds of their titles. “We get tagged constantly in story times from public libraries and readings from individual classroom teachers.”

But one area of concern early on, Gonzalez Cerna says, was learning how to protect authors online. “At the very beginning, Zoom wasn’t as secure….People were harassed and were in uncomfortable situations online,” frequently at bookstore events. Now, he always asks the event host, “What are the protections in place? How are you monitoring comments? How are you monitoring users?” It’s also been a learning curve for authors, he adds: “Not every author wants to be on Instagram, and not every author wants to be tweeting all day long.”

Pandemic buying trends

The main difference between the library market and the bookstore market, Gonzalez Cerna says, is that bookstores are looking for the big-selling titles to help them survive. Simon & Schuster is still seeing the “typical buy,” according to Leo: best sellers, favorite authors, award winners, backlist staples. “But we’re also seeing an increase in more diverse titles, BIPOC titles, and also books about feelings, social-emotional learning, inclusion, and acceptance,” she says, citing Christian Robinson’s You Matter and Our Favorite Day of the Year by A.E. Ali and Rahele Jomepour Bell.

Waintraub has seen a demand for social-emotional and mindfulness books for all ages, and “books that are more inclusive, which also goes to the times that we live in.” Buyers also want new books by known authors. “Kids are looking for comfort,” she says.

|

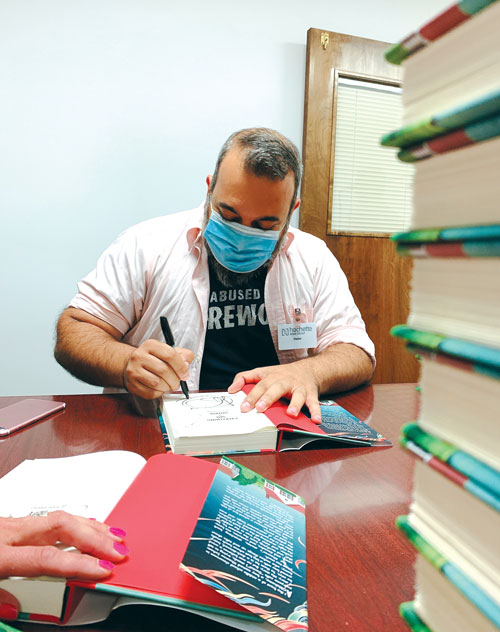

Daniel Nayeri signs books at the Hachette warehouse in Indiana.Photo courtesy of Lucy Del Priore |

Del Priore says that graphic novels have been stronger than ever in middle grade and YA, citing Flamer by Mike Curato as an example. Gonzalez Cerna expects a demand for nonfiction in the coming months, as parents and other community members “create learning opportunities for kids at home.” As the call for #OwnVoices titles grows, he notes that that’s Levine Querido’s entire focus, including current titles such as Everything Sad Is Untrue: (A True Story) by Daniel Nayeri and Elatsoe by Darcie Little Badger.

The movement for racial justice and equity has made more of a lasting impact on her marketing than the pandemic, Kim says, “which is how it should be.” She is focusing on authors of color “who are telling both really vibrant stories [of] joy, but also these powerful narratives about change.” Inkyard’s big title for 2021 is One of the Good Ones by sisters Maika and Maritza Moulite, publishing in January.

Regardless of what happens with the pandemic, virtual marketing is likely here to stay. The pandemic “brought the change faster and made us all realize the potential faster than it would’ve taken otherwise,” Del Priore says.

Looking ahead, Gonzalez Cerna envisions that in-person events could have supplemental virtual components. An author who lives in Australia could participate in a panel via Zoom. “We wouldn’t have thought of that as a possibility maybe a year ago,” he says.

Waintraub says, “I know that teachers and librarians are dealing with so many outside forces. I hope things settle down, and libraries and schools open up fully, and we can get back to focusing on books, on just getting together and talking about books.”

“A school library’s always been the place where you think the most long-term about a book,” adds Stapleton, and it’s more important to think that way now. “You don’t go back to normal,” she says. “You go forward into a new normal.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a freelance writer and editor.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!