SLJ Technology Survey: AI Under Debate

School libraries are focusing less on technology since the pandemic. But AI and its role in education are top of mind, our latest survey shows.

School libraries have been focusing less on tech since 2019, according to SLJ’s latest tech survey.

MethodologySLJ emailed a survey invitation to a random selection of U.S. school librarians on March 3, 2023, with a reminder on March 10. The link was advertised inSLJ’s Extra Helping newsletter for two weeks. The survey closed on March 17 with 595 respondents. Data reported in total has been weighted to represent the NCES breakdown of schools in the United States. |

While school librarians are still largely considered school tech leaders, usage is down, and librarians’ priorities are shifting. Regarding the future of artificial intelligence (AI) in schools, some respondents see possible educational uses, while others believe it will stifle creativity and encourage cheating.

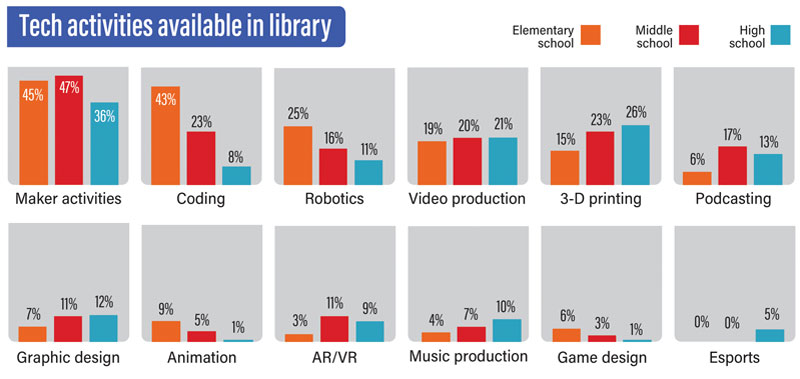

According to the survey of 595 U.S. school librarians, 55 percent of school libraries offer tech-related activities, down from 79 percent in 2019. School libraries offering coding or audio/video production activities have decreased significantly; coding dropped from 60 percent in 2019 to 32 percent in 2023 and A/V from 40 percent to 20 percent.

Librarians still take on a leadership role in introducing and teaching technology, but this has also decreased since 2019. Currently, 57 percent are responsible for library tech use, compared to 71 percent pre-pandemic. Among those responsible, 77 percent said it’s officially part of their job description.

Forty percent of respondents help introduce tech in classrooms, a drop from 45 percent in 2019; and 36 percent said teachers and students use the library to learn new technologies, down from 43 percent.

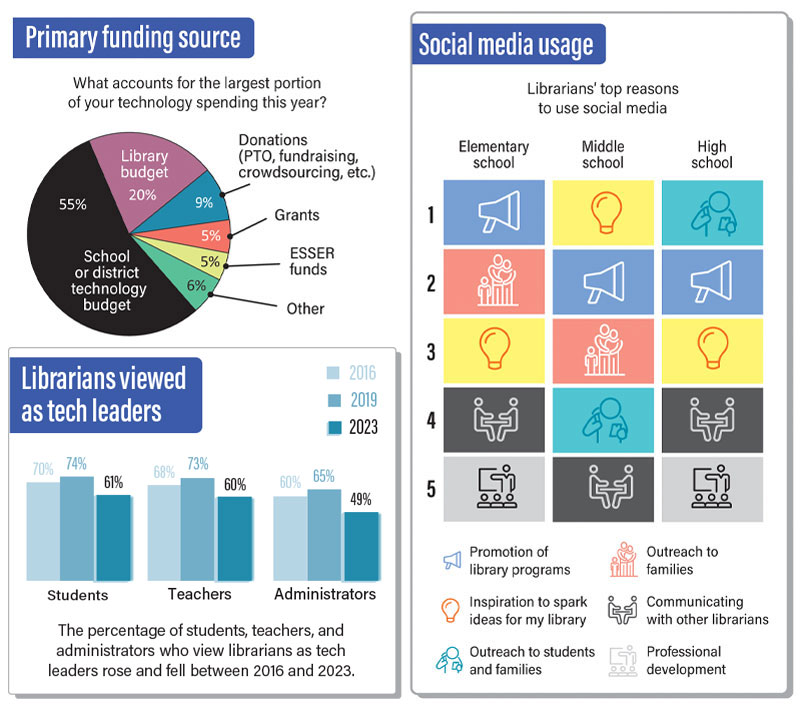

Respondents also said they take on additional tech-related duties as part of their jobs, such as serving on school or district tech teams. And teachers and students see their librarians as tech leaders in around 60 percent of all schools, more so than administrators at 49 percent. Private schools show slightly lower numbers than public schools, with 50 percent of students, 46 percent of teachers, and 39 percent of administrators thinking this way.

Purchasing power

When librarians assist with tech purchasing decisions, it most often involves buying databases in the upper grades, while elementary and middle school librarians are more likely involved in purchasing circuitry kits or robots. School libraries on average spent $4,498 on tech in 2022–23, ranging from about $3,500 in elementary schools to $7,100 in high schools.

Many librarians said they haven’t faced much opposition in the purchasing decisions. “To keep [helping] students be prepared for the real world, they need to have hands-on experience with A/V, robotics, and relevant technology,” said Marie Davis, library media specialist in the Middle School of Poplarville (MS). “These activities build problem-solving skills. Many of our students are deficient in skills needed to solve problems in the real world.”

“I have really only had to justify the purchase of makerspace equipment in the last eight years I’ve been in my building. And that was a no-brainer, honestly,” said Holly Fuhrman, school librarian at Shiloh Middle School in Hampstead, MD. “My admin was supportive of opportunities for our students to be involved in STEM activities as a club.”

One librarian said the library provides tech for students who might not otherwise have access to it. “We need to help brand-new students that just arrived in this country and have no internet or computers at home,” said the library media specialist from a middle school in Miami-Dade County (FL) Public Schools.

On the other hand, some libraries still don’t offer much in the way of tech. “We do not have staff to implement, so we are just happy to get barcode scanners replaced when they fail,” said a K–12 school librarian in Illinois.

Even those libraries that are willing to spend on tech don’t necessarily have a budget for it. Among respondents, 55 percent of schools use the school or district tech budget, 20 percent use the school library budget, and the rest use one-off funds like grants or donations.

Opinions on AI

AI tools such as ChatGPT have gained prominence in many industries over the past year, but survey respondents had mixed opinions on them. Eleven percent felt positive about AI in education, and 7 percent more negative. Over half didn’t know enough about AI to give an answer.

Proponents said AI has educational value. “Staff can use AI to assist in creating lessons and students can use AI to learn more on a topic prior to writing a paper. Educating about AI could also encourage more students to work in STEM-based careers,” said Andrea Caporale, school librarian at Somerville (NJ) High School.

“It’s the new frontier in searching the internet,” added Heather Taylor, school librarian at Folly Quarter Middle School in Ellicott City, MD. “Students should use it like we use Wikipedia. [Find] a secondary source to confirm details, but let AI help you think about the subject in different ways.”

“It’s the new frontier in searching the internet,” added Heather Taylor, school librarian at Folly Quarter Middle School in Ellicott City, MD. “Students should use it like we use Wikipedia. [Find] a secondary source to confirm details, but let AI help you think about the subject in different ways.”

But other respondents think AI will prevent students from learning needed skills. “It’s important for students to learn how to craft an argument, do research, create materials, etc., before they are assisted by AI,” said Sarah Hale, school librarian at Reno Elementary in Azle, TX. “I worry that AI will take away students learning those skills.”

“I think AI can be used in education if done thoughtfully,” added a Montana high school teacher librarian. “But so far it has shown itself to be racist, sexist, and not always accurate. I respect creators (artists, authors, etc.), and AI draws on their work without giving them credit. Students who ask AI to write for them aren’t showing their learning the vast majority of the time.... I’m so far not convinced the pros outweigh the cons.”

Only 4 percent of respondents’ schools have a student AI usage policy, and 19 percent are in the process of drafting one. Several said their schools block access to AI tools and using them for assignments is considered cheating. A North Carolina high school librarian said, “Many do so anyway.”

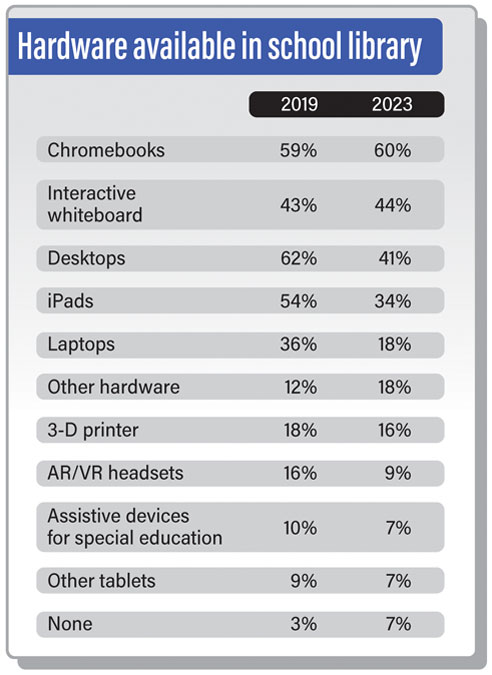

Other types of tech tools showed varying degrees of popularity. In terms of hardware, Chromebooks were the most popular choice, offered in 60 percent of school libraries, up one percent since 2019. Interactive whiteboards trailed at 44 percent. Desktop computers and iPads, at 41 and 34 percent, respectively, dropped from 62 percent and 54 percent in 2019. The “other hardware” category—for example, robots, coding kits, and maker equipment—revealed the only significant increase, from 12 percent to 18 percent.

School libraries that had no hardware for students were at 7 percent, up from 3 percent in 2019. Of those, 14 percent were private schools and 5 percent public.

Student activities

Student activities

The two most common tech activities libraries offer were maker activities and coding. Maker projects were most popular among all school levels at 43 percent, while coding was especially popular in elementary schools.

Code.org was one of the most common coding tools cited. “I love it because it is user friendly for both students and educators,” said Karen Patterson, librarian at Webb Elementary in Arlington, TX. Others included Scratch, the Hour of Code initiative, Kodable.com, and Spheros.

Maker tools tended to be more low-tech, craft-oriented tools like Cricut cutting machines, Legos, origami materials, Keva planks, games, puzzles, and Perler beads. Canva was a popular choice for graphic design projects. “Canva is my new favorite! We have used it to create historical posters and timelines, video book trailers, social media posts for the library media center,” said Maryland middle school librarian Holly Fuhrman.

Aside from Canva, other free tools that respondents mentioned were Flip for student book talks/reviews or to answer questions, Kahoot! for games, Adobe Spark for videos, Unsplash for stock photos, Epic Books for ebooks/audiobooks, MyBib to generate citations, and TinkerCad for 3D design.

Just over half of respondents used social media for work, primarily Facebook. Elementary school librarians were most likely to use social media to promote library programs (73 percent), while middle school librarians used it for inspiration (69 percent), and high school librarians relied on it for outreach to students and families (81 percent).

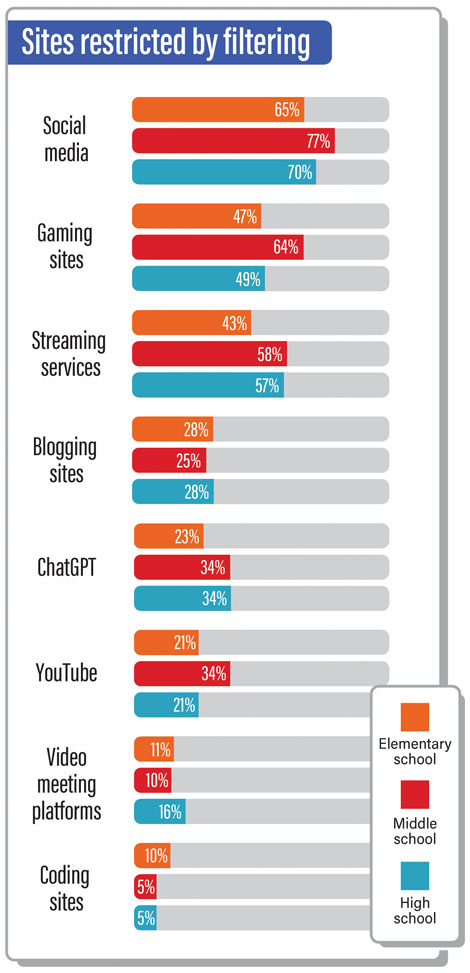

For overall internet use, 90 percent of respondents said their school offers adequate internet access, with 10 percent reporting inadequate access—an improvement from 2019, when 22 percent of respondents reported poor access. Internet filtering restricted social media usage in 68 percent of respondents’ schools, gaming sites and streaming services in nearly half, and blogging sites, ChatGPT, and YouTube in around a quarter.

At the 45 percent of schools that block certain sites, librarians can have them unblocked. Of all respondents, 67 percent of private school librarians can do this, versus 42 percent of public school librarians.

Challenges to tech tools didn’t seem to be a big problem, at 4 percent overall and 8 percent among high schools. Sometimes parents complain about inappropriate content on some platforms.

Challenges to tech tools didn’t seem to be a big problem, at 4 percent overall and 8 percent among high schools. Sometimes parents complain about inappropriate content on some platforms.

“Sora was brought up because of books with mature content available to elementary students,” said a high school librarian in Missouri.

One respondent had a different tech problem. “Students were figuring out how to wipe Chromebooks from school management,” reported a California high school librarian.

As for student access to outside devices, 45 percent of respondents track 1:1 devices in their school, while 42 percent track makerspace equipment.

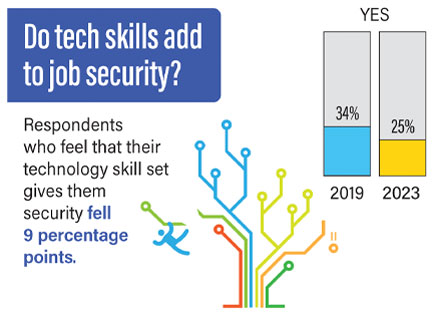

Even though many respondents said tech is an important part of their jobs, 31 percent didn’t think those skills would help with job security; just 25 percent said they felt more secure in their jobs, a decrease from 34 percent in 2019.

And some respondents felt the best thing to use with students was no tech, preferring to read to them instead. “The kids spend so much time on devices that I like to break that up a bit. I am not anti-technology, it’s just they are so distracted by their cell phones,” said Laura Ellis, middle school librarian in Montgomery County (MD) Public Schools.

“Parents and caregivers need to step up their game reading with their kids at home,” added Lisa Ross, elementary paralibrarian at Ramona (CA) Elementary School. “This is the number one free action that will improve students’ reading and comprehension and success in school.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a writer and editor with a passion for children’s books.

Marlaina Cockcroft is a writer and editor with a passion for children’s books.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!