“1619 Project” Poised to Reframe Teaching of Slavery. Here's How Educators Are Using the Information, Curriculum

The New York Times Magazine's 1619 Project and companion curriculum is being used by teachers to change the narrative of American history lessons in the classroom.

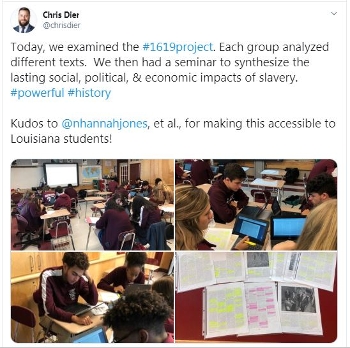

For Chris Dier, the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project—a holistic examination of slavery from its origins to the present day through a collection of essays, poems, and works of fiction—came at exactly the right time. Dier, a world history and AP human geography teacher at Chalmette High School in St. Bernard Parish, LA, was about to start a unit on slavery when the magazine was released in August.

“My students are aware of the basics,” says Dier, who himself was captivated by the project. “But with 1619, a lot of it goes deeper into the analysis. In my class, we connect everything back to how it impacts them in the present, and this mentions New Orleans several times. My students were pretty taken aback; they loved it.”

Dier is among the educators around the country moved by the depth of the project, from its exploration into the impact slavery had on the U.S. economy and how that factors into present-day capitalism to the racist policies that led to the American health care crisis of today. These lessons have been taught over the years by some historians and talked about mainly in African American circles. But the 1619 Project, conceived by  Times Magazine staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones and timed to mark 400 years since some 20 to 30 enslaved Africans were brought by ship to Point Comfort in Hampton, VA, has reignited conversations on how American history is taught in the classroom.

Times Magazine staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones and timed to mark 400 years since some 20 to 30 enslaved Africans were brought by ship to Point Comfort in Hampton, VA, has reignited conversations on how American history is taught in the classroom.

“Now we’ve provided a foundation that the entire society can engage a body of knowledge that’s really grown up over the last century,” says Walter Greason, honors dean emeritus at Monmouth University in New Jersey. “A hundred years ago, this conversation would have been beyond impossible. It was inconceivable.”

1619 curriculum

To underscore the importance of the work and to facilitate engagement, the New York Times Magazine partnered with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting—a nonprofit news organization that supports in-depth reporting on issues to educate the public and improve lives—to produce a free, downloadable 1619 curriculum for educators. It includes everything from a reading guide to questions to consider before and after exploring the project to lesson plans and activities. According to the center’s website, more than 1,000 teachers have reached out to say they plan to use the curriculum in their classes.

Dier didn’t use the Pulitzer curriculum at Chalmette High School, however. Instead, he devised his own plan. He divided his students into small groups, and they picked an article to present to the class. In addition to analyzing the text, students were asked to explain how it connects to today. After finishing one report, they picked another article and repeated the exercise.

It was a truly enlightening experience for the class, he says. Many of the essays resonated with the teens—a mix of white, black, and Latinx students—because they live in the shadows of Louisiana’s sugar cane industry, the economic engine that funded slavery there. In fact, many of their parents work at Domino Sugar in Arabi, LA, which was featured in an essay in the 1619 Project by Harvard professor and historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad.

“I thought it was a fascinating, yet scary, set of articles which enlightened me to the struggles of African Americans that have not been covered in school previously,” wrote one of Dier’s students when asked to react to the project. “It showed me the idea of complete equality is far from real in America and that much more must be done to achieve it.”

Beyond the educational value of the lessons, Dier hopes he’s developing a new generation of critical thinkers.

“It made a direct connection between the history and something that’s real and tangible in their lives,” says Dier, who was named the 2020 Louisiana State Teacher of the Year. “I think it was beneficial for my white students to be provided with that historical context. That way, when they hear certain things in the future that are purely partisan or biased, we can get them to think differently of another group or race or ethnicity. They can remember what they’ve learned and the experiences they had in class.”

A new foundation

Lori Jackson also used the project to make comparisons between historical events and the present. An adjunct professor at Wayne County Community College District in Detroit, Jackson used the 1619 podcast as a primer on the American economy. One episode explored the parallel relationship of the federal government’s prop-up of the cotton industry to the banking industry bailout. The students in her Intro to Business class also discussed how plantation owners were enriched on the backs of their slaves.

“Looking at the disparity between the wealth these people were making. I actually had one white young lady speak up and say, ‘It’s just like what’s going on with GM,’ ” Jackson says, of the General Motors strike.

Jackson says the themes covered in the project are multi-genre, because slavery’s roots are deep and its impact systemic, making it perfect for a business course. A lot of white Americans today don’t consider themselves the beneficiaries of slavery because their ancestors didn’t own slaves, she says. That point prompted a class discussion on the economic injustices that were a result of the transatlantic slave trade, such as land theft, lack of affordable housing, and denial of G.I. Bill benefits.

Jackson says it took some time to get students on board with the lessons. “A lot of these are students that haven’t had a great foundation in terms of education up to this point. So getting them to engage at first was difficult.”

Reframing the way American history is presented is indeed the goal of the 1619 Project, according to its editors. For some educators, like Katie Lapham, it also presents an opportunity to expose some of our youngest learners to the topic early on.

Reframing the way American history is presented is indeed the goal of the 1619 Project, according to its editors. For some educators, like Katie Lapham, it also presents an opportunity to expose some of our youngest learners to the topic early on.

Lapham—an English as a New Language teacher at P.S. 58 The Carroll School in Brooklyn, NY, which serves K–5 students—is hoping to receive federal Title 3 grant funding to create an after-school enrichment program based on the project.

“Often the way slavery is taught is very superficial and limited to key figures like Harriet Tubman,” she says. “And we’ve failed to make connections to appreciate and consider the legacy of slavery in this country and the legacy of oppression.”

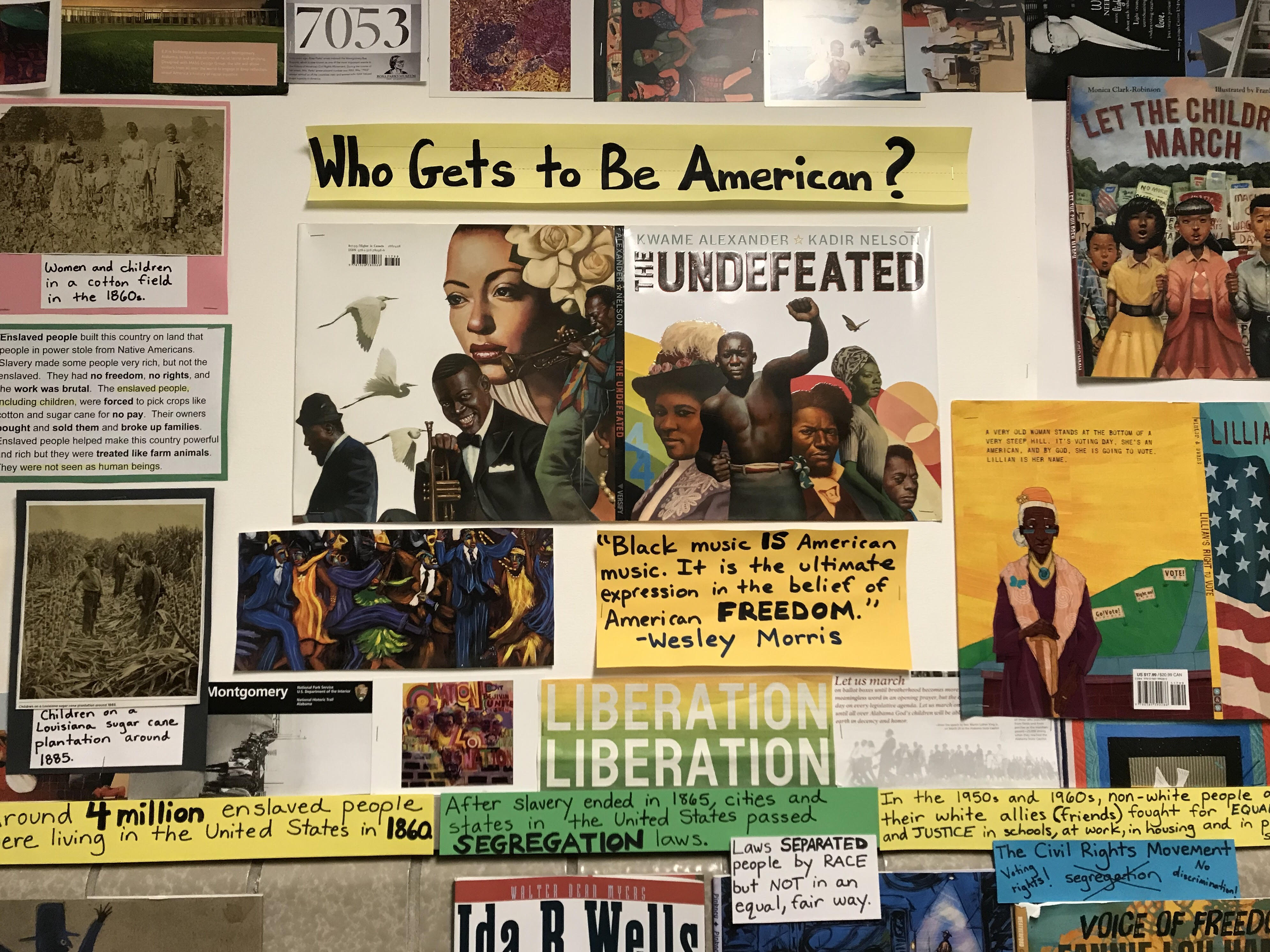

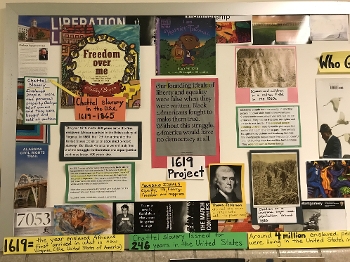

Lapham wants to explore African Americans’ struggle for full citizenship in her program, posing the question, “Who gets to be American?” on the bulletin board outside her office. She’s already received administrative support and positive parental feedback.

While she awaits approval, students, staff, and parents can engage with the images, articles, quotes, questions, and facts she posted on her bulletin board (pictured above and left) highlighting some of the key themes explored in the project, such as music.

“Black music is American music. It is the ultimate expression in the belief of American freedom,” New York Times critic-at-large Wesley Morris wrote about the relationship between slavery and music, and how black sound has been co-opted since the early days.

Reaching those who need it most

Lapham says she wants her program to complement the social justice work already done in her school by some of her colleagues, including a Black Lives Matter Week of Action.

“There are just pockets of events; it’s not across the board,” she admits. She hopes one day there will be widespread efforts, especially because her school is 75 percent white.

Greason applauds the effort and is curious to see which districts embrace and support educators who want to build upon some of the project’s themes. He says he’d expect educators in larger cities, such as New York, Philadelphia, or Chicago, to integrate it into their lesson plans. But it’s critical for rural small towns and homogenous suburbs to also decide it’s important enough to have meaningful discussions about the wide-ranging effects of slavery in America.

|

Walter Greason |

“So much of my life has been about bringing that content to school districts and states that are hostile to it,” says Greason, whose digital humanities projects include “The Wakanda Syllabus” and “The Racial Violence Syllabus.” “If the curriculum can penetrate those communities—and become serious starting points for conversations and transform the way residents of those communities look at the discourse around racism in this country—then I think we are at the beginning of a transformative moment.”

Christina Joseph is an editor, writer, and content strategist.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

K Schmidt

We can all assume victim status and find resources to back us up. But, framing the past with today's woke culture is completely out of context. I'm surprised ALA, SLJ, and entities that support reading/readers continue to inhibit minority opinions. Libraries used to be a place to find freedom and inspiration. Not allowing certain books to see the light of day, whether publishing or purchasing, is the same as book banning. Libraries and publishers should be welcoming various opinions and be places for freedom of the press (like my library), not bullies/judges forcing their mantra on unsuspecting patrons/children. There is so much to write, and I have to get to work, but ALA has wimped out. In writing this comment, my issue is not with slavery. Slavery is a horrible practice. (There are more people in worldwide slavery today than during the entire time from 1619-1864 in the colonies and United States.) My issue is that many libraries have lost their independence, thanks to ALA and their wokeness. Please go back to providing information, not influence, and be the resource every reader needs.Posted : Nov 14, 2019 02:25