12 Essential Nonfiction Graphic Novels for Kids and Teens

The graphic format can effectively tell complex stories and engage young readers. Encompassing first-person accounts of historical events and guides that address gender and identity, these titles meet the highest standards for nonfiction and are "inclusive, respectful, accurate, and informative."

|

Barmaleeva/Getty Images |

Your graphic novel section is likely the most magnetic area of your library. Kids gravitate to entertaining comics-style adventure, humor, fantasy, and realistic stories, often reading these books again and again (and again!).

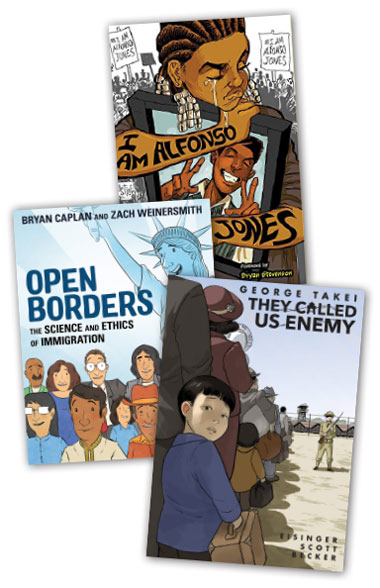

Increasingly, creators are using the graphic novel format to tell difficult, complex stories. In recent years, award-winning books like John Lewis's “March” trilogy (Top Shelf), Jarrett J. Krosoczka’s Hey, Kiddo (Scholastic/Graphix, 2018), and Tony Medina’s I Am Alfonso Jones (Lee & Low/Tu, 2017) foster empathy by offering windows—and mirrors—into different worlds. The expressive art in Jerry Craft’s Newbery Award–winning New Kid (HarperCollins, 2019) provoked a visceral response to its protagonist’s anxiety; images conveying strong emotions can be far more powerful than prose works.

Increasingly, creators are using the graphic novel format to tell difficult, complex stories. In recent years, award-winning books like John Lewis's “March” trilogy (Top Shelf), Jarrett J. Krosoczka’s Hey, Kiddo (Scholastic/Graphix, 2018), and Tony Medina’s I Am Alfonso Jones (Lee & Low/Tu, 2017) foster empathy by offering windows—and mirrors—into different worlds. The expressive art in Jerry Craft’s Newbery Award–winning New Kid (HarperCollins, 2019) provoked a visceral response to its protagonist’s anxiety; images conveying strong emotions can be far more powerful than prose works.

Stories of refugees, genocide, and immigration, as well as books that grapple with consent and gender identity, benefit from the nuance of a pictorial format. Stylized cartoon art directs the reader's focus to what the creator thinks is important—whether it's a passerby’s reaction or action in the background. Artists can emphasize crucial details in a way that photographs cannot and provide big-picture context.

Whether or not the following books fit a given library's age range, the compassion-building titles discussed here are recommended reading for every library professional.

In Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith’s Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration (First Second, 2019), which argues that we shouldn’t put restrictions on the movements of immigrants, , incarceration rates, population statistics, and voting patterns—dry numbers when expressed in prose—become not only comprehensible but memorable. Abstract concepts such as fiscal collapse, cultural disintegration, and the relationship between IQ and production (insert crossed-eyes emoji here!) are gracefully and even humorously communicated via visual metaphor. A huge amount of intelligence is conferred via a few fun panels in this work that’s best for high schoolers or advanced middle school kids.

The panel format lets creators elide or imply scenes that might be too graphic for young readers by “fading to black” or making them happen in the space between panels. In Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed’s When Stars are Scattered (Dial, Apr. 2020) , a middle grade work of fiction based on Mohamed’s living experiences in a refugee camp in Kenya, young Omar, his brother Hassan, and several others are set upon by bandits. Hiding in the bushes with his brother and several terrified girls, Omar narrates, “They took our food, they took our clothes, they took… everything” reads the narration as Omar and Hassan hide in the bushes next to a group of terrified girls.

Older readers may interpret the girls’ facial expressions as an indication that they are in danger of becoming victims of sexual violence, while elementary school students are less likely to catch this. By allowing the art to convey the threat, Jamieson and Mohamed keep the work suitable for a wider audience.

Illustrated stories also allow for contradictions between story and reality. In George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy (Top Shelf, 2019), cowritten by Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, Takei describes his experience being held in an internment camp during World War II. Takei was very young when his family was forcibly relocated from their home in California; his mother brought a bag of sweets and books to entertain him and his siblings on the long train ride, and Takei remembers the journey as a marvelous adventure. Harmony Becker’s art provides a more grown-up perspective, depicting poor conditions and the worried expressions of the adults.

Illustrated stories also allow for contradictions between story and reality. In George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy (Top Shelf, 2019), cowritten by Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, Takei describes his experience being held in an internment camp during World War II. Takei was very young when his family was forcibly relocated from their home in California; his mother brought a bag of sweets and books to entertain him and his siblings on the long train ride, and Takei remembers the journey as a marvelous adventure. Harmony Becker’s art provides a more grown-up perspective, depicting poor conditions and the worried expressions of the adults.

Takei’s point of view remains intact (“I can only imagine what thoughts were passing through his head in that moment…”) while the art fills in the gaps—without forcing Takei to write about details he doesn’t remember.

Graphic nonfiction titles like Takei’s, or historical fiction in graphic novel format, such as R.J. Palacio’s Sydney Taylor Book Award–winning White Bird (Knopf, 2019), which centers on a young Jewish girl in hiding during World War II, catapult middle grade readers into unfamiliar contexts without pages and pages of prose description. In White Bird, the art focuses on the characters, with just enough background detail to establish mood and setting. Context is provided in an incidental, natural way, and the illustrated format conveys a documentary quality that not only makes difficult concepts easier to understand but also imparts a level of trust.

Graphic novels often have the advantage of brevity. Students will brag, “I read this book in an hour!” making them very appealing for class reads. Books that are this accessible, and contain art as visual markers, also make discussion more fruitful. Kids are more likely to find the passage they’re talking about and more likely to reread important sections, or even the whole book.

Many grown-ups dread addressing challenging topics such as sexuality, relationships, and body autonomy with young people. However, study after study has shown that it is essential to teach children about these concepts—and the earlier the better.

Rachel Brian’s Consent (for Kids!): Boundaries, Respect, and Being in Charge of You (Little, Brown, Jan. 2020) takes much of the awkwardness out of finding appropriate language, instead relying on easy-to-understand cartoon graphics. The creator of the viral video “Consent: It’s as Simple as Tea,” Brian explains the concept of consent and bodily autonomy by using analogies that sit comfortably within the scope of an elementary-age child’s experience or comprehension. Kids might have to hold an adult’s hand when crossing a parking lot, but it’s fine to ask the adult to ease up on their grip. If a person has agreed to let someone hurl pies at your face in the past, they have the right to change their mind.

Like many graphic novels, this is a book with a light touch. Because the art carries much of the pedagogical load, it can afford to be short—and even funny. Though injecting humor into books can be misinterpreted as flippant or inappropriate, especially in books on such sensitive subjects, graphic novels can accommodate two tones simultaneously; while the text is busy with a serious explanation of asexuality, as in Mady G. and J.R. Zuckerberg’s A Quick and Easy Guide to Queer and Trans Identities (Oni, 2019), the art can entertain readers with images of goofy snails listening to music.

Like many graphic novels, this is a book with a light touch. Because the art carries much of the pedagogical load, it can afford to be short—and even funny. Though injecting humor into books can be misinterpreted as flippant or inappropriate, especially in books on such sensitive subjects, graphic novels can accommodate two tones simultaneously; while the text is busy with a serious explanation of asexuality, as in Mady G. and J.R. Zuckerberg’s A Quick and Easy Guide to Queer and Trans Identities (Oni, 2019), the art can entertain readers with images of goofy snails listening to music.

Aimed at older teens, this text, like Archie Bongiovanni and Tristan Jimerson’s (even quicker and even easier) Quick and Easy Guide to They/Them Pronouns (Oni, 2018), tackles a complex topic—in this case, the spectrums of gender, orientation, and attraction—and uses visual metaphors, cartoon exaggerations, arrays, and floating symbols to cover a lot of ground in less than 100 pages.

Targeted at younger kids, Heather Corinna and Isabella Rotman Wait, What?: A Comic Book Guide to Relationships, Bodies, and Growing Up (Limerence, 2019) hits the humor even harder, with a cartoon platypus commenting from the margins. Chapters on puberty, masturbation, and sexual identity, along with a memorable page on “weird genitals” (“Worried your genitals look weird? You’re probably right”) contain anatomical illustrations that will have middle schoolers cringing—but readers won’t be alone; the book’s characters are right there with them.

These books are inclusive, respectful, accurate, and informative—they meet the highest nonfiction standards. More readable than the encyclopedic prose tomes on bodies and relationships, they are also more up-to-date and candidly describe how to treat others with respect—and how to recognize when someone isn’t respecting you.

When I show nonfiction or historical graphic novels like those listed above to parents, they often remark, “I wish this book was around when I was learning about…” Do yourself a favor and add these books to your own reading list and to your library.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!