School Libraries 2021: Advocacy is a Necessary Part of the Job for School Librarians

Battling threats to library funding and positions and educating the community on the value of librarians often becomes like a second job, taking up nights and weekends with conversations, events, and social media posts.

|

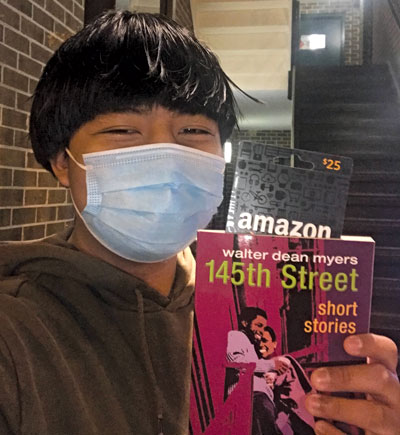

As part of their advocacy efforts, DC Public Schools librarians and supporters held a “read-in”

|

|

SPECIAL REPORT A Pandemic Tale in Pictures |

Curating, booktalking, teaching media literacy—and fighting for your job? Increasingly, school librarians say, advocating to keep their positions is part of their daily work.

Advocacy is not an educational buzzword to these librarians. Battling threats to library funding and positions often becomes like a second job, taking up nights and weekends, in conversation and on social media. But it is the only way some see to stem the tide of school districts phasing out librarians nationwide.

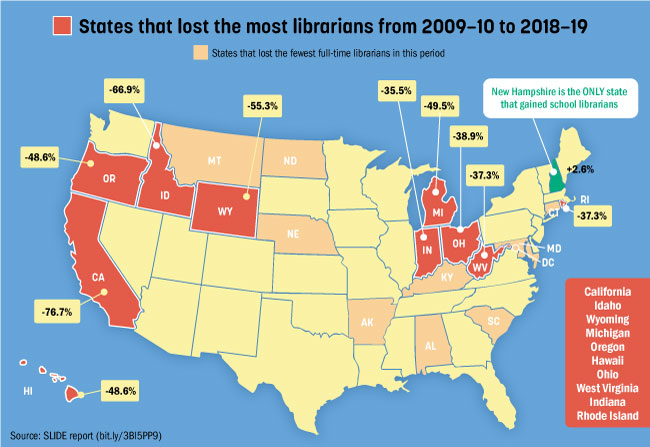

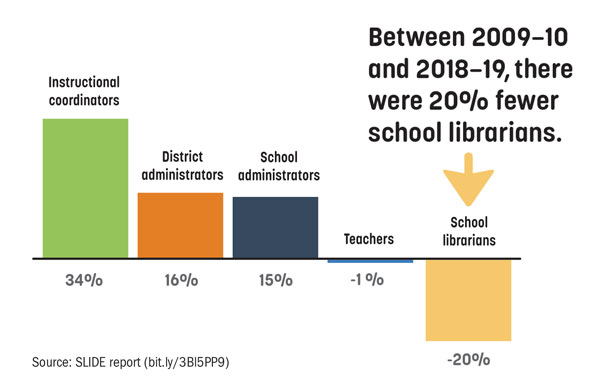

A July 2021 report by the School Librarian Investigation—Decline or Evolution? (SLIDE) research project found that 20 percent of full-time school librarian positions were slashed between 2010 and 2019. The impact is most acutely felt in large urban areas and small rural communities.

As school librarians see their jobs threatened, they are speaking out and finding new ways to spread the word about the importance of their work and what is lost when they are replaced with support staff and/or parent volunteers.

Research shows that the work of school librarians boosts student achievement, particularly in reading. School librarians have always helped children discover new books and assisted with research. Today, they’re also charged with teaching students media literacy, civics, technology, life and career skills, and more.

The titles (librarian, teacher librarian, library media specialist, etc.) and requirements for the job vary by state (bit.ly/3mvtB4M). But the core mission remains the same: Offer access to books and promote a love of reading, empower effective researchers, and provide an equitable learning space that fosters curiosity and critical thinking.

In early 2020, K.C. Boyd, a Washington, DC, middle school librarian, and her fellow DC Public Schools (DCPS) librarians began mobilizing after the district changed funding rules to allow principals to reallocate money earmarked for librarians. Boyd and her peers wanted the district to require a librarian at every school.

With the help of EveryLibrary, a national political action committee for libraries, the DC group launched a petition campaign, scoring a meeting with Lewis D. Ferebee, DCPS chancellor, and representatives of the Washington Teachers’ Union. Library advocates organized FaceTime calls with parents, librarians, and city council members to discuss the work being done in district libraries, the impact on students, and why it is invaluable. In the most visible piece of their advocacy campaign librarians and their supporters held a June read-in on the steps of the offices of the mayor and city council. Over the course of two hours, about 100 people sat there quietly reading.

The action, Boyd says, was highly effective.

“We did the exact opposite of what they expected us to do,” says Boyd. “When people normally protest at that site, they’re kind of loud; they have signs; they’re banging drums and cowbells—and we sat down and silently read. That’s what we do. We are librarians. We read. We support our students, and we support the community. We showed through a quiet gesture how serious we were about the work that we were doing.”

During this long campaign to save school libraries, there was never a work stoppage. “We were consistent in providing service to our students,” says Boyd. “We never wavered in that area, even though it was upsetting for some of us, because some people lost their positions last year.”

She also cites their positive approach in social media posts and with the media.

“Though it was a very heightened emotional time for many of us, we still remained professional,” says Boyd. “We did not trash DCPS in the news, because at the end of the day, this is our employer, and we understood that we have to try to get along.”

In August, an amendment passed calling for a full-time librarian in all 115 schools in the district.

|

K.C. Boyd (left) and Christopher Stewart (center) led the advocacy efforts in DC that eventually prevailed, guaranteeing librarians in schools for another year.Photo courtesy of K.C. Boyd |

Their public campaign also helped spur DC city council member Charles Allen to introduce the Right to Read Act, a bill that would guarantee a librarian in every year starting in fiscal year 2023 and “each subsequent fiscal year.”

A win, for sure, but these efforts to justify the value of their jobs—and do it in a big enough way to make a difference—are exhausting. They amplify school librarians’ baseline stress from the lack of job security and concern over how their absence would impact the students, who are often the kids who need the most support.

Whether a school has a librarian often depends on where that school is located.

“Children attending suburban schools are more likely to have full-time librarians, while those attending more urban and rural schools are more likely to have no librarians at all,” says Keith Curry Lance of the RSL Research Group and the principal investigator for the SLIDE study.

Both Boyd and Christopher Stewart, who is in his fifth year as a DCPS school librarian, teach at urban, majority-Black schools in high-poverty areas. The SLIDE study found that districts with the most students living in poverty were much less likely to have school libraries.

So, for many librarians, this type of advocacy work is about much more than keeping their jobs. It’s also about making sure the most disadvantaged kids have access to the resources they so desperately need.

“I’ve always been a champion for the underdog,” says Stewart. “This is my calling: to make sure that I am literally ending injustice—and I consider it an injustice. I consider it a civil rights issue when you do not make it equitable to have a school librarian in every school.”

|

|

Photo courtesy of Christopher Stewart |

Equity is an issue in many large cities . In Seattle, the difference between the North End and South End neighborhoods is the difference between properly supported, full-time school librarians and a patchwork of staff and funds.

Anne Aliverti, an elementary school librarian in the wealthier part of the city, can turn to parents and caregivers when needed. At Bryant Elementary, she holds a readathon fundraiser that brings in money for new books. Through her parent teacher student association (PTA), Aliverti can hire a paid library assistant for eight hours a week. And she has many parent volunteers who help with checkouts, shelving, and maintenance, so she can focus on teaching and running library programs. But Aliverti knows that librarians elsewhere in the city, like JK Burwell, don’t have that luxury of support.

“You have parents who are pulled in so many different directions; some of them are working two jobs,” says Burwell, who splits her time between South End schools John Muir Elementary and Graham Hill Elementary.

“The equity issues in Seattle are ridiculous. PTAs in the North End can pick up a lot of stuff that we have to put in our budgets in the South End.”

Aliverti has been politically active since becoming an educator in 1996. She’s been a union representative, served on the bargaining team during teacher strikes, spoken out to the PTA on behalf of the library’s needs, and is an active member of her building’s race and equity leadership team. Being involved with other school departments and aligning the library’s services to common goals builds value and visibility, she says.

“A librarian has to take risks,” Aliverti says. “You have to do things that are maybe not quite in the mainstream or in your comfort zone, but you have to go out and take a risk.”

Communicating how a librarian’s role contributes to the school and the wider community is a large part of creating credibility, says Sarah Logan, a teacher librarian in the Camas School District near Washington State’s southern border. She sends out newsletters and monthly statistics about the library and gives updates at PTA meetings to strengthen relationships with parents.

“Whenever parents want to thank me for a program, I tell them, ‘I appreciate hearing that, and I hope that you’re letting the school board and the superintendent know that as well,’” she says. “I feel very listened to in my district, but parents are super listened to.”

|

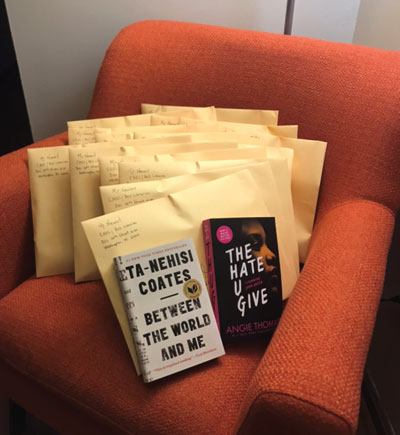

Christopher Stewart dropped off and mailed books to students when school was remote because of COVID.Photo courtesy of Christopher Stewart |

After one of her updates to the PTA about the state of her library, a parent approached Logan about creating a library liaison position within the PTA. Having a point person to share concerns and victories has been helpful in spreading awareness about the library’s role, Logan says. This type of advocacy can trickle up, and it can be less intensive for librarians who don’t have extra time or resources to advocate for legislation.

New York City Public Schools (NYCPS), the country’s largest public school district, is experiencing a school librarian hiring boom. It comes after a large advocacy campaign, with support from the New York City School Librarians’ Association (NYCSLA).

“It was a group effort to get NYCPS to hire more school librarians,” says Arlene Laverde, NYCSLA past president, a librarian at a Queens high school, and president-elect of the New York Library Association. “When I was president of NYCSLA, we had a social media campaign where we tagged the NYC DOE, the chancellor, the national PTA, and other groups daily on what school libraries with certified librarians had to offer.”

Laverde says NYCSLA’s current president, Jillian Rudes, met with the chancellor’s office to highlight librarians’ impact, supporting student learning and district goals particularly during virtual learning necessitated by the pandemic. The city schools’ Department of Library Services also promoted school librarians and reminded principals about the mandates regarding these positions.

“It was a complete group effort that really came together,” says Laverde.

But there is still work to be done. Of the 1,700 public schools in New York City, Laverde says only 600 have a school librarian. A state mandate calls for a librarian in every middle and high school, but Laverde says the district hasn’t reached that.

“It’s mandated by the state, but it’s an unfunded mandate,” says Laverde, who also cites stereotypes about librarians and misconceptions about what they do as reasons for the shortage of school librarians in the city. “We need to educate people on what librarians do.”

She explains that in New York State, librarians are required to be certified teachers, a point that she emphasizes when she talks about her job.

“When I tell people about my job, I say I am a school librarian, I am a certified teacher,” says Laverde. “I make sure I let people know that teaching is the number one priority of my job.”

Librarians’ work often looks different than what administrators or other teachers think of when it comes to delivering instruction.

“Pretty much every period of the day that I’m around people, I’m teaching them—whether it’s a whole-class instruction, a colleague that I’m teaching how to find something or how to use material, a professional development that I’m running, or an individual student who I’m teaching how to search,” says Laverde.

But because most librarians don’t work in a classroom, their roles as educators can be less than obvious, a point that can hurt them when school leaders are allocating their budgets.

Most schools only have one librarian, so when that position is cut, the whole department is shut down. John Chrastka, founder and executive director of EveryLibrary, says it can take years to feel the consequences of that move.

“They try and paper it over,” says Chrastka. “They’ll bring in literacy coaches. They’ll bring in volunteers, and by the time we’re far enough down a couple academic years on the calendar to realize we’ve made a bad decision, the school library might have turned into classroom libraries, or it’s so out of date it’s just a reading room.”

When librarian positions are lost, the SLIDE study also found that they are rarely restored. According to the report, in 2015–16, 3,560 districts nationwide (28 percent) had eliminated all school librarians. Nine out of ten of those districts without librarians had not reinstated them by 2018–19.

Even when administrators know a librarian’s value, once that line is cut from the budget, it can be hard to justify returning it when the district has many other needs. That is the story in the Camden City (NJ) School District, where school libraries and librarians were eliminated about a decade ago. Even with the influx of COVID relief funds, superintendent Katrina McCombs says it would be fiscally irresponsible to dedicate grant money to a costly initiative to restore those positions without knowing if she could sustain it.

“Libraries are powerful; libraries promote and foster a love for reading,” she says. “But I have to be sure that we do not fall off of a fiscal cliff afterwards.”

Debra Kachel, who teaches at Antioch University Seattle and is the project director for SLIDE, notes that there are places where kids are growing up without ever setting foot in a school library.

“This then impacts the whole library ecosystem,” says Kachel. “If we are graduating kids from high school [who] have never known a school library or librarian, and then, when they become taxpaying citizens, we expect them to support libraries—well, that’s not going to happen.”

With once-in-a-lifetime federal funding on the line, Chrastka says school librarians must be bold, organize, and act at the “very local” level and make a clear argument that their position better serves the educational goals of their district than another position would.

This new framework for advocacy and activism will involve “aligning support from the union, interest among other teachers and educational stakeholders, and administration to create not just a position but a standards-focused local policy that ensures students have access to what a school library program is designed to do,” he says.

Marva Hinton is a freelance journalist, a contributing editor at Edutopia, and host of the ReadMore podcast. Lauren J. Young and Christina Joseph contributed to this story.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!