Lee Bennett Hopkins Left Legacy of Anthologies, Careers Launched, and the Call To Infuse Poetry Daily Across the Curriculum

Hopkins's impact on poetry for children went beyond his prolific creation of anthologies. He championed cross-curricular use of poetry and allowing children to read for enjoyment, while jump-starting the careers of many poets along the way.

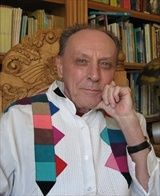

When Lee Bennett Hopkins died on August 8, he left a legacy that showed his incredible impact on poetry in general and poetry for children, specifically: More than 120 anthologies of poetry for children, his own work, countless poets whose careers he launched or who he inspired and helped, poetry awards he founded and funded, and story after story of blunt criticism and seemingly limitless generosity of time and spirit with fellow poets.

|

Photo by Charles Egita |

"What really distinguished Lee? First, the way he championed poetry across the curriculum,” says Janet Wong, a poet and children’s author.

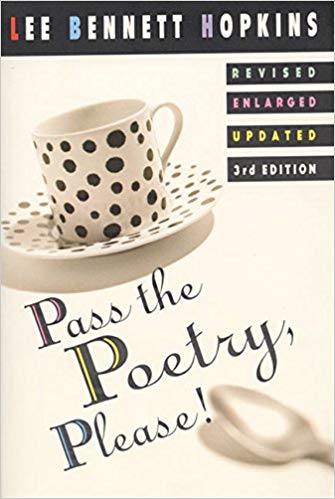

In his 1972 anthology, Pass the Poetry Please, Hopkins wrote, “It is my firm belief that poetry can and must be an integral part of the total school curriculum, interwoven within every subject area.”

“That was really revolutionary at the time when he started putting anthologies together,” says Wong.

When Hopkins won the NCTE Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children in 2009, Wong and Sylvia Vardell put together Dear One: A Tribute to Lee Barnett Hopkins, which was a collection of poems from more than 50 poets about Hopkins and his impact on their careers.

One of his biggest impacts he had was seeking out diverse voices to include in his books.

“He was ahead of his time for sure,” says Vardell, a professor of children's literature at Texas Woman's University, author of Poetry Aloud Here! Sharing Poetry with Children in the Library, and creator of the blog “PoetryForChildren.” Vardell notes that Hopkins put together a children's anthology of poems by Langston Hughes in the 1960s and sought poets of color when compiling an anthology. “He was really good about, that and sometimes that meant seeking out brand new voices that hadn’t been published elsewhere. He launched a lot of people that way,” she says.

Hopkins was known to mentor young poets and mix their work with the established voices. He also shaped poems with his editing, request for new drafts, and, at times, biting criticism. But poets sought his approval, knowing a compliment from Hopkins was hard-earned.

“He was very generous, very loving, very kind, but also very critical,” says Vardell. “He just felt like he was the arbiter of the quality and the relatability for children. He wasn’t wrong. The books sold. They’re read by kids.”

Indiana high school English teacher Paul Hankins was a huge admirer of Hopkins. When Hopkins died, Hankins brought two crates of his anthologies into school, using the moment to introduce his students not only to Hopkins but also the many poets he spotlighted in his anthologies. The 11th graders looked through the books to identify a poet and a poem they liked. Then, they practiced their citation of a poem, a poet, and an edited collection of work.

Indiana high school English teacher Paul Hankins was a huge admirer of Hopkins. When Hopkins died, Hankins brought two crates of his anthologies into school, using the moment to introduce his students not only to Hopkins but also the many poets he spotlighted in his anthologies. The 11th graders looked through the books to identify a poet and a poem they liked. Then, they practiced their citation of a poem, a poet, and an edited collection of work.

“This helped us to anchor our celebration of the poet with skills our students need to continue to work on early in the year,” Hankins wrote in an email.

Then, the more creative part of the activity began. “The students then used their chosen line to inform their own poem,” Hankins wrote. “What I get to see as the teacher is students writing poetry informed and inspired by the likes of Rebecca Kai Dotlich, Jane Yolen, Charles Ghigna, Amy Ludwig VanDerwater, Janet Clare, and Matt Forrest Esenwine, and many, many more. And I got to see my students write poetry informed and inspired by [Hopkins] himself.”

It’s not always easy to get high school students to read poetry. Hankins says he is always concerned that they just don’t know very many poets. Hopkins believed that students should be exposed to poetry as often as possible, and without strict rules.

“He said once—and I’ve used this in my teaching a lot—to avoid the DAM message,” says Vardell. “DAM stood for Dissect, Analyze, and Memorize.”

While middle and high schoolers may not have a long list of favorite poets these days, thre popularity of novels in verse point to an ongoing engagement with the poetic form.

“We couldn’t have verse novels that are as successful as the verse novels by Jacqueline Woodson, Kwame Alexander, and Margarita Englel but for Lee’s work, pioneering work,” says Wong. “They liked to call him the pied piper of poetry.

“That being said, he was very, very adamant that verse novels could not replace collections or anthologies of poems," she adds." Very often in verse novels, you don’t have the same variety of poetic technique that are used. In telling a story, a lot of verse novelist’s find that variety in technique get in the way. I do remember Lee lamenting this. What you find with some verse novels is that there’s very little music in the verse. The novel part comes first. With the best verse novels, you have it all—you have the story and the music.”

Neither Vardell or Wong hesitated when asked what people could do to honor Hopkins.

“If every teacher in America would read poems every day, he would have been thrilled,” Vardell says. “It’s really that simple. He just felt like everybody would be a better person if they had a diet of poetry…. He would just want more of it out there. Every day. Every kid. Every classroom.”

Wong agrees, and adds, “If people wanted truly to honor him, they would mount a campaign for ALA to have a poetry award.”

Vardell says that she has tried in the past, she says, but ALA resisted. Vardell says she was told that the organization already had too many awards and couldn't fund or manage adding another. But, she maintains, it’s time to pick up that banner again.

“Maybe that will be Lee’s spirit carrying us forward to get that to happen,” she says. “We all know the awards encourage publishing. It all comes down to the marketplace, trying to get more books on more shelves and into the hands of teachers and children.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!