What It Really Means to be "Bad at School" | A Guest Essay by Brigit Young

The middle grade author reflects on her complicated childhood struggles with academics and self-esteem, and how these informed the protagonist of her novel Bright.

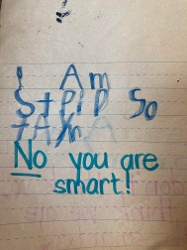

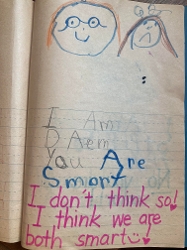

I can’t remember the exact moment I understood I was “bad at school,” but I can recall various comments from others that hinted at it.

I can’t remember the exact moment I understood I was “bad at school,” but I can recall various comments from others that hinted at it.

In second grade, a friend appeared surprised I’d aced a spelling quiz because “that wasn’t [my] thing.” I remember when the concept of division was introduced, I was so obviously flummoxed that a classmate remarked, “Don’t worry, you’re great at singing.” At some point, I grew discouraged enough to tune academics out. I arrived at middle school hopeful for a fresh start, but quickly found I was so shaky in the building blocks of the school curriculum that the typical start-of-school review sessions  were not enough for me.

were not enough for me.

But I had to survive somehow. Each school day. Each hour. And by seventh grade I decided that to avoid hourly humiliation, I would fully embrace “bad at school” as an identity. If I didn’t know an answer, I laughed it off. I joked that I’d never gotten math or geography and never would. I proclaimed watermelon lip gloss as my favorite thing in life. I brushed my hair in class. I constantly discussed my passionate love for Ben Affleck (genuinely felt) and my firm belief that we would one day marry. Back then, we called a girl like that a “ditz," and a “ditz” I became. I was stupid, so I “acted stupid.” Why pretend otherwise? Why put in the effort and try when I was bound to fail in a humiliating fashion?

What I couldn’t see then is that rather than inhabiting an honest version of myself, I was, in fact, still pretending. When kids wrote “You’re my fav ditz!” in my yearbook, or “You’re an airhead but you’re cute haha,” they knew a cultivated persona. When my eighth grade math teacher, frustrated at the deflections and lip gloss reapplications, announced to the class, “She wants to be a ditz, so let her be one,” it hit me that while I’d achieved my aim of finding a way to never get called on, this teacher had it all wrong. She couldn’t see the main issue: I didn’t want to be a ditz. I felt I had no choice.

eighth grade math teacher, frustrated at the deflections and lip gloss reapplications, announced to the class, “She wants to be a ditz, so let her be one,” it hit me that while I’d achieved my aim of finding a way to never get called on, this teacher had it all wrong. She couldn’t see the main issue: I didn’t want to be a ditz. I felt I had no choice.

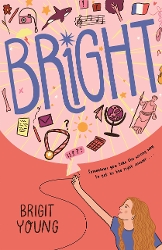

Out of the memories of those academic struggles and low self-esteem, I created Marianne Blume, the main character of my new middle grade novel, Bright. Marianne slides by with Ds and Cs while acting as if she doesn’t care. It’s only when she discovers she won’t make it to high school that she must change her tactics. In a bid for extra credit, Marianne joins her school’s competitive, combative Quiz Quest team, manned by the strict math teacher who refuses to fudge any test scores. In Quiz Quest, Marianne has to find a way out of the box she’s put herself in or she just might find she’s stuck there.

What I couldn’t comprehend about myself back then, and what I attempted to include in Marianne’s journey, is that my survival tactics represented an expression of an intelligence less easily quantifiable than academic knowledge. My choice to “play the ditz” suggested I could read the room and socially comprehend the roles played in school. Much later in life, when I attended college in my mid-20s, that form of emotional acuity translated into skills like dissecting texts, debating ideas, and, fatefully, writing stories. In my author’s biography for the jacket of Bright, I write that I  am a proud graduate of the City College of New York. And I am extremely proud, because little me would never have imagined such an outcome, but that student was hiding inside the whole time.

am a proud graduate of the City College of New York. And I am extremely proud, because little me would never have imagined such an outcome, but that student was hiding inside the whole time.

I wrote Bright for struggling students like Marianne—for the kid I used to be. In Marianne’s path toward recognizing her own shame and forging a way out of it, I hope students not only see some of themselves, but experience a validation of their value. I hope Bright reinforces the message that manifestations of intelligence are enormous and varied. I also want kids who thrive in a conventional academic setting to understand their classmates a bit better. Maybe that kid who never answers doesn’t know where her talents fit in yet, and maybe the student chosen last for class projects has an unexpected quality to offer.

manifestations of intelligence are enormous and varied. I also want kids who thrive in a conventional academic setting to understand their classmates a bit better. Maybe that kid who never answers doesn’t know where her talents fit in yet, and maybe the student chosen last for class projects has an unexpected quality to offer.

Most of all, I wish for readers of Bright to feel sincere hope for Marianne Blume and her future. In an ideal world, kids wouldn’t see “bad at school” as a core piece of their identities, but rather the beginning of a story that holds infinite possibilities, the rocky start to finding their own bright spark.

Brigit Young, born and raised in Ann Arbor, MI, has published poetry and short fiction in numerous literary journals. She is a proud graduate of the City College of New York, and has taught creative writing to kids of all ages in settings ranging from workshops at Writopia Lab to bedsides at a pediatric hospital. Brigit is the author of the middle grade novels Bright, Worth a Thousand Words, and The Prettiest. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and daughters.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!