Pairing Children’s Literature and Primary Sources

Using primary sources with literature can help students explore a story using a unique, real-world perspective.

There may be nothing better than a student exploring a story. Engaging and connecting with a story can impact every student’s perception of the world or of themselves. There are times though that incorporating a primary source with the book can make the experience even more meaningful.

Why pair primary sources with literature?

Students' understanding of a story is partially dependent on their ability to understand and picture the moment. Pairing primary sources with literature can help students explore a story using a unique, real-world perspective that they may not otherwise have.

Compelling primary sources help students contextualize elements of a story to better understand and relate to it. A photograph of an event can help students visualize a setting. Listening to a song only referenced in the text might immerse a reader in a scene. Words written by those in a movement may give voice to a character.

There may also be learning moments where the children’s literature leads to greater understanding of primary sources. A story, fictional or true, can humanize a topic that feels more distant when interacting with  an item from long ago. In these cases, beginning with the story to build contextual knowledge may increase student engagement in analyzing primary sources. Students may also be supported in tackling more complex historical items with that additional support from the literature.

an item from long ago. In these cases, beginning with the story to build contextual knowledge may increase student engagement in analyzing primary sources. Students may also be supported in tackling more complex historical items with that additional support from the literature.

As students begin working with more complex literature in high school or even middle school, primary sources may play another role. Instead of connecting readers to the story directly, the historical items can connect students to the author and the world around them at the time they wrote their story. Understanding the big conversations, societal struggles, or evolving ideas in a moment gives a specific lens when reading literature written during that same time. There may be no better way to immerse students in that time period than through primary sources created at that same time. When students in our high school read 1984 by George Orwell, they also focus on primary sources in a study on propaganda in World War II, specifically in countries with dictatorships.

Historically based nonfiction and historical fiction may be the first types of books considered for this pairing. Don’t stop there. Contemporary realistic fiction that is rooted in realities of the day can utilize primary sources from present day to help establish the reality that an author is writing to. Similarly, we can look to those books written decades ago, whether it is described as a classic or a forgotten work, and ask what was happening in the world around that author when it was written to look for influence on the story. Memoir and biography are other formats that could benefit from a primary source pairing.

Students Roles

Students may take on different roles when they interact with literature and primary sources. Depending on the learning objectives, piece of literature, and available primary sources, students can explore different aspects of reading and writing. Some include:

Author or Illustrator Inspirations from Imagery

Photos and other historical images can provide inspiration for writers and illustrators of literature. Students can deeply explore a primary source image through an analysis. They can bring that knowledge to compare it to the text or illustrations asking the question, “Is there any evidence that the creator of this book may have seen this image in his or her research?” This role can provide powerful examples of how visual medium can inspire and impact the written word.

Exploring an Author’s Inspiration and Process

The previous idea can be expanded to additional formats of stories. Full story arcs can typically be broken down into shorter memorable moments. When working with historically based nonfiction and historical fiction, students may use a selected set of primary sources to look for evidence that the author may have seen the same historical item. This exploration can be expanded upon. When identifying a source that authors may have used in their historical research, students can ask, “What information did the author choose not to include? Why might that be? Would I have made a different decision?”

Examining Character Traits

|

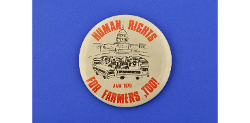

Photo: National Museum of American History |

Characters in a piece of literature are presented in specific ways. They can be described as having specific character traits. When these individuals are historical figures or based on historical figures, students can analyze primary sources to identify character traits of individuals. Whether they are written about, writing about themselves, photographed, or filmed, the creator of that historical document is presenting them in an identifiable way. Students may analyze the literature and the historical document to identify character traits and compare them to see how an individual is portrayed in each. Lindsay H. Metcalf’s Farmers Unite! can be paired with a collection of primary source buttons worn at the protest to explore how farmers are presented in the picture book and how they presented themselves through these artifacts.

Taking on the Role of Author/Researcher

Authors who write historically based nonfiction or historical fiction research the time period they are writing about. They also likely research a specific individual or event that is highlighted in their writing. Students can emulate that research by searching for primary sources related to literature they have read.

Unlike independent research, following the author’s path is meant to illuminate the path the writer took in the creation of their story. The process of students searching for and investigating resources can elevate that role as part of the writing process leading to a better understanding of the text and potentially impact their own future writing.

Taking on the Role of Researcher

Historically based literature can spur unique questions from students. Those questions can be the first step in student-driven research where they delve into a variety of topics where the literature is a jumping-off  point. Primary, as well as secondary sources, can help students find the answers to their personal inquiries and construct meaning stemming from their interaction with literature. As an example, Deborah Wiles’s Kent State, a novel in verse told from multiple perspectives, could lead to questions about the focus of the book. Oral histories collected in connection with the 1970 event could help answer those questions as students continue learning about the event from multiple perspectives.

point. Primary, as well as secondary sources, can help students find the answers to their personal inquiries and construct meaning stemming from their interaction with literature. As an example, Deborah Wiles’s Kent State, a novel in verse told from multiple perspectives, could lead to questions about the focus of the book. Oral histories collected in connection with the 1970 event could help answer those questions as students continue learning about the event from multiple perspectives.

Interacting With Primary Sources

Interacting with a primary source in a purposeful manner is as important as intentionally reading literature. Teaching students specific analysis strategies and modeling them through collaborative classroom use can assist students in developing the habits of historical thinking when working with these types of sources.

If new to primary source analysis, consider using a Visible Thinking Strategy from Harvard’s Project Zero or an adapted analysis strategy, such as a Close Reading analysis, that students already use to analyze other work.

Pairing children’s literature and primary sources has multiple entry points, heightens student engagement, and helps students construct meaning around story and source. Most importantly, the dual focus on traditional literacy and historical literacy centers around students engaging with text and related historical sources to build the connection between the two. Collaborations with classroom teachers at all levels can provide curricular roots to this pairing for the most meaningful learning experiences.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!