Uniting Against Censorship: A First-Person Account from Banned Books Week Youth Honorary Chair

Former Katy, TX, student Cameron Samuels writes about their experience fighting book bans and rallying fellow students to join them.

Footsteps carry me through a winding labyrinth as my finger brushes the surface of paper casing. Carefully torquing the spine at the edge above to bring it to my hands, I catch the effervescent whiff of a good book. It is alive, and it's endowing me with the author's breath and soul. It is a bridge between the physical realm and a conscious, intellectual mind.

Getting lost in literature was my favorite childhood pastime, but the feeling I came to learn was not of loss but of love. Books are an unwavering haven for me, and if you are reading this, I hope you have had the opportunity to experience the same. Please do not forget the incomparable feeling that a good book offers, because I, as a young student in 21st-century America, can no longer take it for granted.

In October 2021, Rep. Matt Krause delivered a letter to superintendents in Texas, including that of my district, urging the removal of 850 books that touched upon race and sexuality. This letter swiftly became a gateway to the removal of thousands of books and many schools denying students access to entire libraries without parent approval.

The rocks of Plato's cave were falling rigidly into place, creating barriers between books and their readers, students and their education. Retrospectively, challenges to particular books are quite frequent over the course of American history, but this was no single accusation—it was a coordinated attack on shelves of books grouped by the ideological diversity they offered.

As consistent but shallow waves of book banning became a politically-motivated tsunami, librarians and students rushed to the forefront of the brigade to rebuild a bridge to books.

Ticks of a three-minute timer were counting down the seconds remaining on the microphone, my legs were shaking, and the sweat of my palms stuck to the phone in my hands. When I finished speaking, I looked up at the focused eyes staring at me from ahead before I turned from the lectern. The room was silent.

I was at a board meeting for the Katy (TX) Independent School District. I had just condemned the administration for censoring vital internet resources for queer youth with a discriminatory internet filter, and moreover, for canceling an author visit with Jerry Craft and removing New Kid from classroom libraries in accusation of teaching Critical Race Theory.

I was at a board meeting for the Katy (TX) Independent School District. I had just condemned the administration for censoring vital internet resources for queer youth with a discriminatory internet filter, and moreover, for canceling an author visit with Jerry Craft and removing New Kid from classroom libraries in accusation of teaching Critical Race Theory.

Tensions at school board meetings were familiar to me after watching several forums prior to speaking that night, but it was the first time I heard silence, not a roaring applause, after a speaker addressed the board and walked back to their seat.

Hearing the reverberation of my words dissolve into a void, I felt damaged and isolated by the evident tension in the room. A few women made ugly gestures as my feet stepped past those sitting near the aisles. Examining my surroundings, I realized not a single student shared the 200-seat room with me. I was inarguably alone.

Sitting in isolation, I listened as speakers that followed me shared disdain of "pornographic and sexual content" spoiling our libraries. The policymakers on the dais gave me a nonresponse, but when it came to the others, the district immediately ordered the removal of the targeted books and established an easier system for challenging books—direct and swift action to "protect the children" while excluding the most vulnerable.

There was no communication from the district to me on this issue, despite continual actions taken to cleanse libraries of diverse topics, until a few days ahead of the next board meeting. The district was worried, not by the apparent growth of extremism, but by the pressure we placed on them with publicity in the press.

I built a movement through the school hallways and social media that month, drawing attention to the district beyond the Katy community and Texas. We galvanized onlookers into action with sharable infographics, gathered petition signatures that grew to thousands, and leveraged the platform the press provided to reach above the floodline of censorship.

At the December board meeting, with winter break right around the corner, I was planning to pack the board room. We weren't going to let bigots and book banners decide the narrative any longer. We were building power amongst ourselves and driving change in a national movement against bigotry, and instead, for compassion.

Recalling the first time I heard of Banned Books Week in middle school, which opened my eyes to the breadth and depth of book banning—people following in the footsteps of fascism rocked me to my core.

At the time, I was becoming aware of the intersections of fact and fiction ahead of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Misinformation and extremism skyrocketed on the campaign trail, leading to what has become an ongoing attack on marginalized identities. I saw it happen, but ignorance left many clueless of this political transformation. I am crestfallen by how we came to this.

We analyzed implicit biases in eighth grade, scrutinized conformity and oppression in my freshman English class through works of literature, and Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 was required reading my sophomore year. We critiqued censorship, not gave in to it, and issues of race and other marginalized identities were focal points in our classroom discussions.

My education taught me to think critically, question the status quo, and to see impermanence in the world—I learned to hold a growth mindset for society, to be open-minded, and to seek a community of compassion.

This is education. We were not indoctrinated. At no time did I feel "anguish" in my white skin like Texas legislators accused the curriculum of imposing; in fact, we were still praising Christopher Columbus and ignoring the horrors of imperialism. I felt rather disheartened by the lack of LGBTQ+ and Holocaust education, among other topics not taught in the state curriculum.

While legislators accused schools of horrifically teaching pronouns and Critical Race Theory, we grew as individuals and leaders, not cogs in a machine of state power. When leaders point their fingers at education and an ever-changing society, we know they are clasping their seats as we speak, trying to preserve power. That's when we refuse to uphold injustice.

Among the groups established in response to the recent, unprecedented wave of book banning, a coalition of Texas educators founded FReadom Fighters to challenge the dangerous investigations initiated by Krause and Governor Greg Abbott. As it had throughout centuries of history, dehumanizing verbiage became common in the words of political leaders nationwide, trickling down into ignorant minds.

|

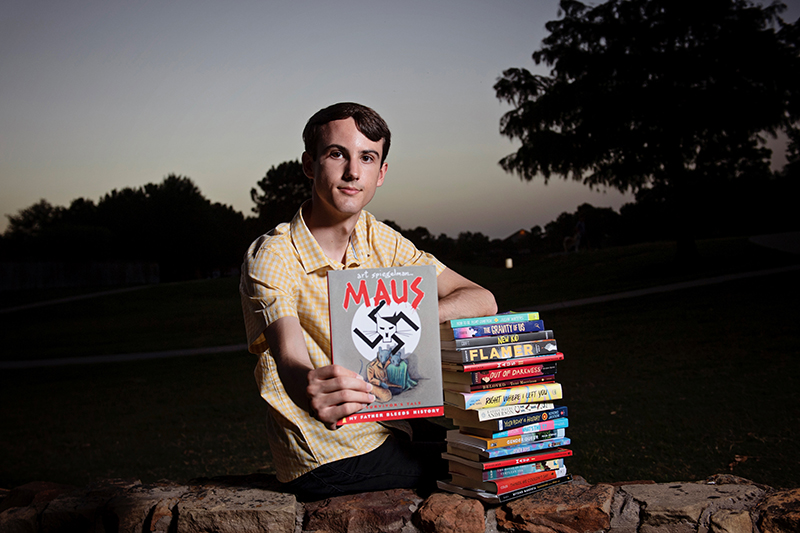

Samuels and their classmates distributed more than 700 banned books to students. |

With the momentum I built in Katy since November, I brought together students at several high schools in February for a FReadom Week effort to eventually distribute more than 700 challenged books and pack another school board meeting defending intellectual freedom.

District officials and community members, not surprisingly, immediately challenged our efforts by initiating reviews on the books we distributed and going as far as threatening to disrupt our events and verbally harassing us at public events—which got even worse with school board elections upcoming.

Katy became a leading district in Texas, not for its academic success or an inclusive school environment, but as a symbol of censorship. Unfortunately, other districts in Texas and across the nation also entered this competition to attest to their conservative principles while scapegoating wokeness. Students had nothing else to do but continue fighting back.

In Leander, a suburb of Austin, students formed a Banned Book Club. Students in the Dallas-Fort Worth area repeatedly denounced the extremism of their school boards as " Christian conservative cell phone companies " bought them out. And across the nation, students from Central York, PA, to Winter Park, FL, fought local book bans.

The student movement is growing, whether policymakers are ready for it or not, and it won't slow down anytime soon without guaranteed access to an inclusive education and an affirming school environment.

"Books unite us, censorship divides us" is the theme of Banned Books Week this year. As educators collaborate with students more than ever before to combat the rise in attacks on free speech and marginalized identities, we will affirm our commitment to ensure students have a seat at the table in decisions that directly affect them.

In the eyes of certain people in power, a single book may simply be a statistic, but in reality, a single book may be the only lifeline accessible to a student. A single book may be everything to a student, and a single ban could leave them in shambles.

Cameron Samuels (they/them), an 18-year-old student from Katy, TX, is the Youth Honorary Chair of Banned Books Week 2022. A list of events featuring them and more information about Banned Books Week can be found here.

.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!