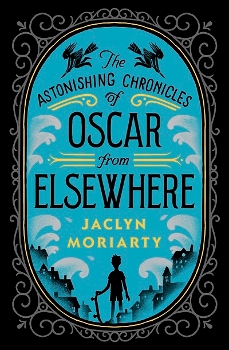

Jaclyn Moriarty Sends Complex Kids on an Epic Quest

Sydney-based Jaclyn Moriarty’s best-selling novels have been named Boston Globe-Horn Book Honor Books and Best Books for Young Adults by the American Library Association. Oscar from Elsewhere is the fourth book set in Moriarty’s Kingdoms and Empires universe.

Adventurers solve puzzles in Oscar from Elsewhere

While working on her PhD in Law at Cambridge University, Moriarty wrote her first novel for young adults called Feeling Sorry for Celia. Since then, Sydney-based Jaclyn Moriarty’s best-selling novels have been named Boston Globe-Horn Book Honor Books and Best Books for Young Adults by the American Library Association. Oscar from Elsewhere is the fourth book set in Moriarty’s Kingdoms and Empires universe. In this magical story for ages 10-14, Oscar and his new friends must act fast to save an elf town trapped under a silver wave.

What do you hope young readers will learn about themselves while reading this book?

What do you hope young readers will learn about themselves while reading this book?

I always hope readers will realize that they are extremely special and valuable people no matter how flawed or alone they might feel—and that there is a friend out there somewhere for them. But I think you can learn varied and unexpected things from any book you read, and those things are more about you than they are about the book. (Also, if any reader wants to just relax and enjoy the story, without learning a thing, I don’t mind that at all.)

Both Imogen and Oscar have distant or absent parents. How do you think that affects their journeys?

Imogen and Oscar are very different people, but both are children with parents who are absent or self-absorbed. This has affected them in different ways. Imogen has become hyper-alert and controlling, and very protective of her younger siblings. Oscar has basically checked out of his life (and into the life of skateboarding). I wanted the book to be about the deep connections you can form with someone whose story intersects with yours in a small but essential way—even if you come from entirely different worlds (figuratively or literally).

Oscar deals with “concentration issues” at school. What inspired you to give him that particular trait?

I was very restless and day-dreamy at school myself—and my son inherited his own version of that restlessness. I found reading books and playing the piano helped me. My son skateboards and plays the electric guitar (so, a cooler approach).

How does the absence of tech like smartphones change things for the kids in this story?

It can be tricky writing books these days because so many problems can be solved with Google and cell phones. I like the fact that there is no modern technology in the southern part of the Kingdoms and Empires, where this quest takes place. It means the children have to find their own creative solutions. It also means that they can be truly cut off from the adults in their lives, giving them an opportunity to shine.

Any chance of giving the trial scene pirates a story of their own?

I did like the idea of a town where pirates can take extended breaks from pirating to live average, honest, suburban lives, so...maybe?

Your undergraduate thesis offered a postmodern deconstructive analysis of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. What was the primary thrust of your argument?

Your undergraduate thesis offered a postmodern deconstructive analysis of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. What was the primary thrust of your argument?

This question is giving me the uneasy feeling that I’ve walked into an exam without having opened the textbook. I know I referred to Foucault a lot, and spent pages and pages on spatial conceptualization in the factory. And I remember my supervisor reading my first draft and saying, “Huh, you actually came up with something. I was sure you were going to ask to switch topics.”

Two of your sisters are also authors. Did your parents encourage literary activities?

When we were little, my dad used to commission us to write stories. We didn’t get pocket money but we got a dollar fifty if we filled up an exercise book with words. So, Dad always liked to take the credit for all three of our writing careers. And now I love having sisters who are also authors. Liane, Nicola, and I are each other’s first readers, and completely understand the importance of effusive, hyperbolic praise.

What was the most surprising reaction to one of your books from a young reader?

A young reader once wrote me a letter telling me she loved my books and adding that I should NOT let that go to my head. My favorite letter was from a girl who told me that whenever she feels sad she hugs one of my books and it makes her feel better.

SPONSORED BY

|

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!