How Can Libraries Support Children and Immigrant Families? By Doing What We Do Best.

The plight of immigrant families at the U.S. border prompted the Brooklyn Public Library and others to act.

|

A young patron participates at a library multicultural program in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn.Photos by Gregg Richards |

In early 2018, after learning about the forced separation of families at the southern U.S. border, Brooklyn (NY) Public Library (BPL) staff looked for ways to help. The Youth and Family Services team reached out to local government, nonprofits, and foster care agencies, but the most direct link to displaced children was through the immigration lawyers representing them, who described hours-long court wait times with their clients, some as young as three. In court proceedings, children were often retraumatized having to describe their experiences crossing the border—sometimes unaccompanied—or of being separated from their families upon entry to the U.S.

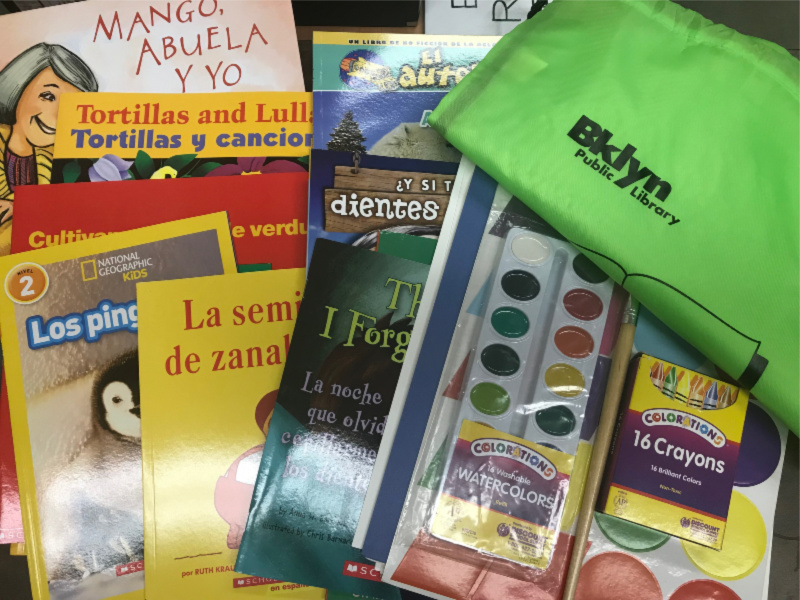

Knowing the stress-relieving power of books, art, and play, BPL staff decided to fill backpacks with age-appropriate books in Spanish, art materials, toys, and activities, which the lawyers distributed directly to children. “[The books] helped the kids feel more at ease and relaxed during the intake process and served as a healthy and comforting distraction while they waited for other parts of the interview process to wrap up,” says Melissa Forero, social service coordinator of Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), a Washington, DC-based nonprofit, which serves children who enter the U.S. immigration system alone. “Watching our clients leave with book bags in hand and smiling was also extremely encouraging for us as a team!”

The cost of family separation

Children in immigrant families make up one-quarter of all children in the United States and represent a fast-growing segment of the country's increasingly diverse child population. Since 2016, there have been significant shifts in immigration policy, which, according to Rebecca Ullrich, a policy analyst at anti-poverty nonprofit Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), “have made many young children vulnerable to being forcibly separated from a parent or other loved one due to immigration enforcement actions, which poses a great threat to children’s emotional security.”

Ullrich and her colleagues Wendy Cervantes and Hannah Matthews, collaborated on the 2018 CLASP report “Our Children’s Fear: Immigration Policy’s Effects on Young Children.” It found that families with young children are isolated in their homes due to fear and have reduced access to early education programs. As the report notes: “They leave their homes for necessary activities— like going to work or buying groceries—yet have stopped frequenting parks, libraries, and retail stores.”

Young children who are exposed to constant stress often suffer lifelong consequences. Even if children have not experienced family separation, “the threat alone is enough to take a toll on children’s mental health and wellbeing,” says Ullrich.

Libraries, be ready to offer consistent resources

One of the most significant ways that libraries can mitigate the impact of this stress is to be a trusted and consistent resource for immigrant families. “Libraries can be a key welcoming space and public institution for kids who are facing a crisis and are seeing the bad side of government and institutions,” says Christian Zabriskie, Yonkers (NY) Public Library branch administrator, and executive director of Urban Librarians Unite. Providing consistent resources may mean more outreach and community partnerships, as families with undocumented relatives change their routines to avoid possible enforcement actions.

If families do come into the library, be ready with the information they need. “We can provide accurate and trustworthy information about changes in immigration law, know your rights information, and the process for naturalization,” says Eva Raison, BPL’s outreach director. “People may not want to ask a staff member directly for help, but will pick up a flier or take a picture of a poster...that give[s] key phone numbers about who to call if someone is detained, how to report a raid, and how to access free legal services.”

|

BPL staff made backpack kits with age-appropriate books in Spanish, art materials, toys, and activities, which local immigration lawyers distributed directly to children. |

What we do best: books

Cervantes and Ullrich recommend that libraries also focus on what we do best: books. “Libraries can help to combat the anti-immigrant rhetoric coming from the highest levels of our government by offering children’s books that affirm and celebrate the diverse cultures and experiences of immigrant families.” Books in the first languages of the children are key, but make sure they go beyond basic translation and celebrate a child’s culture and heritage.

If you are not a Spanish speaker, share books sprinkled with Spanish that celebrate the Latinx experience like One is a Piñata by Roseanne Greenfield Thong (Chronicle, 2019) or Dreamers by Yuyi Morales (Holiday House, 2018). Try I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O'Brien (Charlesbridge, 2015) for a picture book featuring immigrant children from a variety of backgrounds.

Gaining access to migrant children separated from their families has often proven difficult for librarians as federal facilities restrict access for security reasons. Children in Crisis (CIC), a project of REFORMA, the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking, an affiliate of the American Library Association, has provided Spanish and bilingual books to children and families in pro-bono legal offices, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) facilities, shelters, and on both sides of the borders where children and families are waiting to present claims.

“The children and the families have always been so grateful for the books that they receive. Many times these have been the first books that the children can claim as their own.,” says Patrick Sullivan who co-chairs CIC with Oralia Garza de Córtes, workshop leader and consultant.

Taking the library to those in need

Outreach to organizations serving migrant children or bringing those groups to the library is another way library staff can support separated children and immigrant families. The San Diego Public Library gives tours several times a year to kids from a shelter for migrant children. Zabriskie and his colleagues have been working with a secure foster agency in Westchester County, NY, to provide children books and programs. “These kids love the library and cannot believe the lengths that we will go to for them,” says Zabriskie. And if you are struggling to gain access to children’s shelters, Zabriskie says persistence is the key.

With reports of young children facing the prospect of separation from their families, to children in detention for whom this nightmare has come true, it is easy to feel overwhelmed. But we can all make a difference in our own communities doing what we do best: offering resources for assistance, outreach to those who are isolated, storytimes in the languages of the families we serve, and books that celebrate their language and heritage.

“Libraries should be reaching out to immigrant families as they would to any other new member of the community, with the understanding that these families may have limited or no previous exposure to libraries,” says Sullivan. “Making them aware of all the resources available to them, (hopefully in their language)...can reduce an immigrant family's stress and better connect them to your community.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!