The Truth is in There: Creative Approaches to Informational Books for Young Readers

Unconventional narrative strategies are becoming more common in informational books. Plus: 17 recommended titles.

“Hey, you! Pssst! Down here!”

This opening line of Flower Talk: How Plants Use Color to Communicate makes it clear this isn’t a textbook-style work of nonfiction. The speaker is a cranky cactus, fed up with all the meanings humans have attached to the color of flowers. The prickly, personified narrator explains that roses aren’t red to signify love but to attract pollinators, such as birds and butterflies. That nontraditional structure grew out of conversations that author Sara Levine had with her editor, Carol Hinz of Millbrook Press. Levine’s first draft was traditional nonfiction, but Hinz encouraged her to try something different. “I’d love for you to explore whether there’s a slightly more playful or lyrical way to frame this information,” Hinz wrote in an email to Levine. “It might be going too far to propose that a flower narrate the book, but I’m going to throw that out as one possibility just to see if it leads you to  any other interesting approaches.”

any other interesting approaches.”

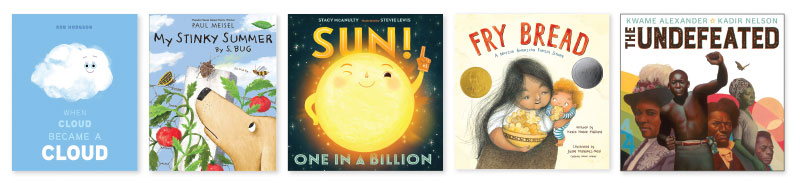

Such unconventional approaches are becoming more common as informational books take center stage in classrooms and libraries. Librarians say that unique voices and structures broaden the appeal of informational texts, enticing more readers to explore topics in science and history. Creative narrators and main characters run the gamut, from a talking sun in Sun! One in a Billion to the microbial narrator of Germs: Fact and Fiction, Friends and Foes, a salmonella bacterium who goes by Sam for short, to joyful Cloud, of Rob Hodgson’s When Cloud Became a Cloud. Like Levine’s grumpy cactus storyteller, these personified subjects add personality and humor.

|

Flower Talk (cactus) illustration and photo (right) both courtesy of Lerner Publishing Group |

“Ideally, the fictional elements will give readers a point of entry into the book that makes the information more accessible and will help readers to engage with the topic in a way that deepens their understanding,” Hinz says.

Author-illustrator Paul Meisel takes a similar approach in My Awesome Summer by P. Mantis (A Nature Diary), a picture book whose six-legged narrator adds a dose of humor.

“The diary format was the first idea that popped into my head,” Meisel says. “I thought if the praying mantis presented serious topics like cannibalism and survival in a deadpan, matter-of-fact way, then it could be both entertaining and informative.” He’s taken a similar approach inMy Stinky Summer by S. Bug and My Tiny Life by Ruby T. Hummingbird.

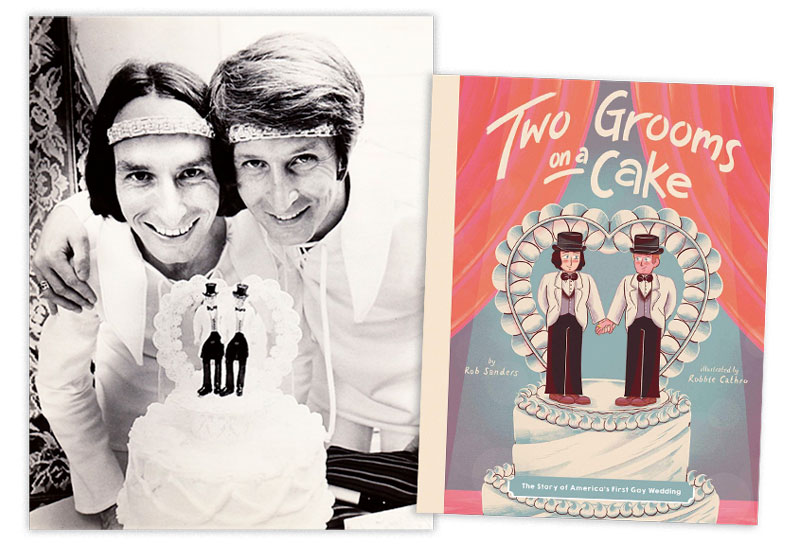

Accessibility for young readers was a major consideration for author Rob Sanders as he revised the text for T wo Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding, which is narrated by the cake toppers at the big event.

“I thought about the weddings I attended as a child and what I enjoyed most about them,” Sanders says. “The answer was, of course, the cake. And that’s when the parallel stories of how a cake is made and how a relationship is formed came to be. Since the cake topper is part of the actual, historical story, it seemed like a great way to bring readers into the story.”

Sometimes, an invented narrator is a child who serves as a proxy for the reader. That’s the case in my own nature picture book Over and Under the Canyon, in which a boy and his mom explore the rich ecosystem of a desert canyon. Young explorers narrate the journey in poetic language in each story in the series ( Over and Under the Snow, Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt, Over and Under the Pond, Over and Under the Rainforest ), while the books’ back matter provides more traditional nonfiction text about the animals seen along the way.

Two books in one

Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story takes a similar approach, with Kevin Noble Maillard’s spare text and Juana Martinez-Neal’s warm, lively illustrations of a family preparing and enjoying traditional fry bread, coupled with detailed back matter about the food’s cultural history. Kwame Alexander and Kadir Nelson’s poetic picture book The Undefeated uses this model as well, offering inspirational verse alongside illustrations of historic Black figures who go unnamed in the primary text, with biographies for each in the back matter.

This poetry-in-the-pages, facts-in-the-back style affords teachers and librarians the opportunity to share titles aloud, even when time is limited, giving curious readers more information to explore in back matter that’s often written in a different style and voice. Readers end up getting two books wrapped into one.

“Those are the types of books that I like to write and gravitate toward,” says Maria Gianferrari, the author of Be a Tree! “Ones that are spare and poetic, with either layered text like sidebars, or rich back matter that lends depth and weight to the main text.”

“Be a tree!” her book begins. “Stand tall. Stretch your branches to the sun.”

The primary text draws poetic connections between trees and people, while the back matter is more traditional, offering up “Five Ways You Can Help Save Trees” and a detailed infographic showing “The Anatomy of a Tree.”

Authors’ choices in informational texts

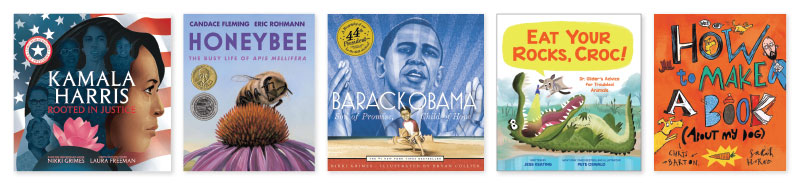

Candace Fleming, the author of Honeybee: The Busy Life of Apis Mellifera, chose to keep her biography of a honeybee grounded firmly in the realm of nonfiction. The emotional narrative follows a single honeybee from birth to first flight to her eventual death. Though the honeybee is an imagined representative of the species and not a specific bee, Fleming only included details that are universal and chose not to anthropomorphize the bee.

“Nowhere in the text do I assign thoughts and feelings to Apis,” Fleming says. “Nowhere do I say, ‘She couldn’t wait to fly,’ or ‘She leapt joyfully from the hive.’ Instead, I let my readers bring their thoughts and feelings to the story, and I hoped they’d assign them to my honeybee.”

It was a delicate balancing act that required Fleming and her editor to scrutinize every word to make sure the book wasn’t drifting too close to fiction.

But for other stories, introducing elements of fiction can help to frame the facts. Nikki Grimes chose a story-within-a-story structure for her picture book biographies of Barack Obama (Barack Obama: Son of Promise, Child of Hope) and Kamala Harris ( Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice), with fictional children talking with their parents about the U.S. leaders.

“With a picture book biography, I always like to make sure it appeals to the youngest readers, as well as the older ones,” Grimes says. “This story-within-a-story format makes it a wonderful book for mothers and grandmothers to read to and with readers too young to navigate this book, or handle some of its vocabulary, on their own.”

Other informational titles introduce fictional elements to add humor. How to Make a Book (About My Dog), a work of metafiction about creating a book, takes a conversational tone on the first page, where readers find an illustration of author Chris Barton introducing himself, and his dog Ernie, the subject of the book. One spread features the faces of people recalling memories of Ernie; one woman reminisces, “Remember when Ernie met my cat?” Next to her is a cat whose thought bubble reads, “I hate Ernie!” Barton goes on to share detailed information about book making, from edits and revisions to agents, acquisition meetings, book design software, and distributors.

|

Jack Baker and Michael McConnell, the subjects of Rob Sanders’s book.Photo by Paul Hagen |

The shelving question

Informational books that feature fictionalized elements raise questions for media specialists: Where should such titles be shelved? Are they fiction or nonfiction?

For some, talking cacti and cats with thought bubbles introduce a fictional element that takes a book out of the realm of strict nonfiction. But more often than not, librarians are making shelving decisions based on the primary purpose of a text rather than whether or not the cats or cacti talk. It comes back to the kids, they say. Where will a reader interested in this topic be most likely to find it?

Some librarians keep multiple copies of popular informational picture books—one for each section where a reader might look for it. When that’s not possible, most say that if a title’s primary purpose is to inform, it usually lands in nonfiction, and if storytelling takes center stage, it tends to live in the regular picture book section.

There are special considerations when the subject matter of a book deals with the history of traditionally marginalized people. Grimes prefers to see her Harris and Obama biographies shelved in nonfiction.

“It’s vital that readers understand that stories about accomplished Black people are real, historically sound works of nonfiction,” she says, “rather than something imaginary. Shelving such books in the nonfiction section makes that clear.”

Sanders feels the same way about Two Grooms on a Cake. “I know how few children’s books there are about LGBTQIA+ history. I would like to see books about my community sitting alongside books that show other communities who have struggled for equality.”

In making shelving decisions, librarians are also sensitive to how biographies about people from traditionally marginalized groups are represented, especially when a white author chooses to write the first-person narration in a biography of a person of color. For that reason, many librarians that carry Brad Meltzer’s “I Am…” series about famous people (which includes stories about Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., Frida Kahlo, and others) choose to shelve these books with historical fiction, rather than with nonfiction biographies.

Bringing readers into the conversation

There are rich conversations to be had about the lines between fiction and nonfiction as readers explore informational texts, and many teachers and librarians welcome the opportunity to engage students in critical thinking.

“I think this first came up when we started reading informational books that had illustrations instead of photographs,” says Lynn Svec, a second grade teacher at Glenbrook Elementary, part of a large suburban school district in Illinois. She introduces her students to a wide variety of informational texts, pairing traditional nonfiction featuring photographs with illustrated books that take more creative approaches with the text, such as Lita Judge’s The Wisdom of Trees, Jess Keating’sEat Your Rocks, Croc!, and Rob Hodgson’s When Cloud Became a Cloud.

Svec asked her readers, “If you were going to look for this book in a bookstore or library, where would you expect to find it?” Students weren’t always sure, and they had in-depth discussions about the balance between fact and fiction.

“This book has a lot of information, but the clouds have faces on them and clouds don’t really have faces,” one reader responded.

Svec was delighted that the books sparked more discussions about elements of fact and fiction in their favorite titles—and more enthusiastic reading of all kinds of informational texts.

Informational Books and Creative Approaches |

|

|

The Undefeated by Kwame Alexander. illus. by Kadir Nelson. Versify. 2019. How to Make a Book (about My Dog) by Chris Barton. illus. by Sarah Horne. Millbrook. 2021. Germs: Fact and Fiction, Friends and Foes by Lesa Cline-Ransome. illus. by James Ransome. Holt. 2017. Honeybee: The Busy Life of Apis Mellifera by Candace Fleming. illus. by Eric Rohmann. Neal Porter. 2020. Be a Tree! by Maria Gianferrari. illus. by Felicita Sala. Abrams. 2021. Barack Obama: Son of Promise, Child of Hope by Nikki Grimes. illus. by Bryan Collier. S. & S. 2008. Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice by Nikki Grimes. illus. by Laura Freeman. Atheneum. 2020. When Cloud Became a Cloud by Rob Hodgson. Rise x Penguin Workshop. 2021.

|

The Wisdom of Trees by Lita Judge. Roaring Brook. 2021. Eat Your Rocks, Croc! Dr. Glider’s Advice for Troubled Animals by Jess Keating. illus. by Pete Oswald. Orchard. 2020. Flower Talk: How Plants Use Color to Communicate by Sara Levine. illus. by Masha D’yans. Millbrook. 2019. Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story by Kevin Noble Maillard. illus. by Juana Martinez-Neal. Roaring Brook. 2019. Sun! One in a Billion by Stacy McAnulty. illus. by Stevie Lewis. Holt. 2018. My Awesome Summer by P. Mantis (A Nature Diary) by Paul Meisel. Holiday House. 2017. Over and Under the Canyon by Kate Messner. illus. by Christopher Silas Neal. Chronicle. 2021. Over and Under the Snow by Kate Messner. illus. by Christopher Silas Neal. Chronicle. 2011. Two Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding by Rob Sanders. Illus. by Robbie Cathro. Little Bee. 2021 |

Kate Messner’s new “History Smashers” nonfiction series aims to unravel historical myths and share hidden truths.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!